LONDON -- British Prime Minister Tony Blair went to war alongside the U.S. in Iraq in 2003 on the basis of flawed intelligence that went unchallenged, a shaky legal rationale, inadequate preparation and exaggerated public statements, an independent inquiry into the war concluded in a report published Wednesday.

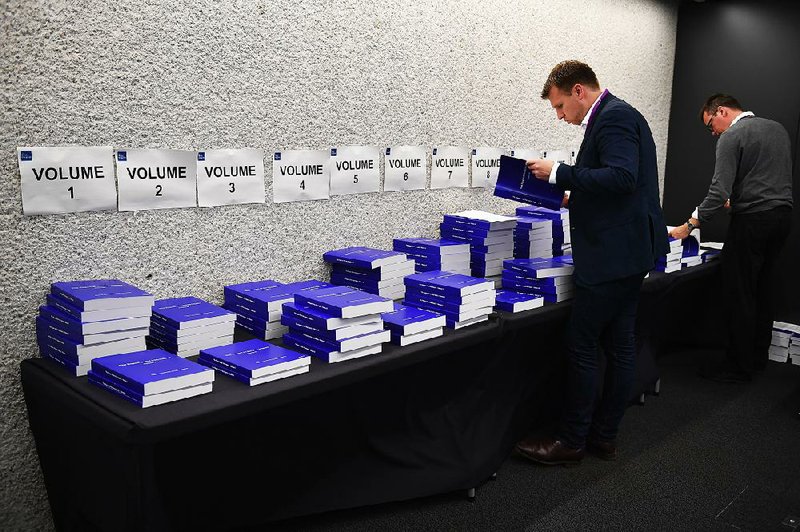

The report by the Iraq Inquiry Committee, led by John Chilcot, takes up 12 volumes using 2.6 million words and took seven years to complete, longer than the United Kingdom's combat operations in Iraq.

It concluded that Blair and the British government underestimated the difficulties and consequences of the war and overestimated the influence he would have over President George W. Bush.

Blair, however, stood by his decision to join Bush in toppling Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.

"I believe I made the right decision and that the world is better and safer as a result of it," he said Wednesday.

Bush spokesman Freddy Ford said the former president was cycling with wounded veterans on his Texas ranch and had not had the chance to read the report.

"Despite the intelligence failures and other mistakes he has acknowledged previously, President Bush continues to believe the whole world is better off without Saddam Hussein in power," Ford said.

The report describes a prime minister who wanted stronger evidence of the need for military action and a more solid plan for occupying Iraq and reconstituting a government there.

But the report revealed a note sent personally from Blair to Bush, dated July 28, 2002, roughly eight months before the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq.

"I will be with you, whatever," Blair wrote, in what appeared to be a blanket promise of British support if the United States went to war to topple Saddam, the Iraqi leader. Getting rid of Saddam was "the right thing to do," Blair wrote, predicting that "his departure would free up the region."

The 2002 note warned broadly of the risks of "unintended consequences" from an invasion and presciently forecast that other European nations would be reluctant to back the war. But by the time the invasion was begun, most of Blair's warnings and conditions had been swept aside, the report concluded.

Chilcot said Wednesday that Blair had been advised by his diplomats and ministers of "the inadequacy of U.S. plans" and their concern "about the inability to exert significant influence on U.S. planning."

Blair chose to override their objections.

The report said the United Kingdom found itself excluded from most important decisions about the military campaign and its aftermath.

"Mr. Blair, who recognized the significance of the post-conflict phase, did not press President Bush for definite assurances about U.S. plans," the report concluded.

And it said that after the invasion, Britain had only "limited" ability to influence U.S. decisions.

Foreseen consequences

The inquiry's verdict on the planning and conduct of British military involvement in Iraq rejected Blair's contention that the difficulties encountered after the invasion could not have been foreseen.

"We do not agree that hindsight is required," Chilcot said. "The risks of internal strife in Iraq, active Iranian pursuit of its interests, regional instability and al-Qaida activity in Iraq were each explicitly identified before the invasion."

Blair's concern before the invasion of Iraq, the report makes clear, was less about the need to overthrow Saddam than about how to justify doing so.

The intelligence that Blair presented in public had a great deal more certainty than his officials presented in private, the report said.

The report says: "At no stage was the hypothesis that Iraq might not have chemical, biological or nuclear weapons or programs identified and examined" by Britain's Joint Intelligence Committee. The Bush administration had promoted invading Iraq as a way to eliminate its weapons of mass destruction.

"The UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted," the report said. "Military action at that time was not a last resort."

The report concluded that Blair and the British government both underestimated the difficulties and consequences of the war and significantly overestimated the influence he would have over Bush.

In particular, Blair's note to Bush was part of what the report showed to be a campaign to back the U.S. before the war and to steer the White House toward building diplomatic support for efforts to address the perceived threat from Iraq.

A draft of the note to Bush, classified "Secret-Personal," was circulated to two senior aides, David Manning and Jonathan Powell. The report disclosed that they urged Blair to soften or delete the "I will be with you, whatever" declaration and not to tie his political fate too tightly to Bush's judgments.

Manning, a former ambassador to Washington and Blair's chief foreign-policy adviser, testified that he had told Blair the sentence was "too sweeping," that it seemed to "close off options" and that there was "a risk it would be taken at face value."

Blair later said he thought he had amended the sentence, but he had not.

The results of the invasion have haunted Iraq, the U.S. and the U.K. ever since. By the time British combat forces left Iraq, the conflict had killed more than 200 Brits, including 179 soldiers, at least 4,500 Americans and more than 150,000 Iraqis, most of them civilians. Sectarian warfare and terrorist groups have filled the vacuum left by Saddam.

Just this week, at least 250 Iraqi civilians died from a car bomb in Baghdad as they celebrated the final days of the holy month of Ramadan.

Chilcot said that "the people of Iraq have suffered greatly" because of a military intervention "which went badly wrong."

Blair on missteps

Blair's legacy as prime minister, from 1997 to 2007, has been defined in the U.K. almost entirely for his decision to go into Iraq alongside the United States. The current leader of the Blair's Labor Party, Jeremy Corbyn, has gone to far as to apologize for the party's directing British forces into the war.

As Chilcot introduced his report at a London conference center, dozens of anti-war protesters with placards reading "Bliar" rallied outside.

Within hours of the report's release, Blair appeared at a nearly two-hour news conference in which he acknowledged missteps and intelligence failures but defended his decision to go to war.

He said, "I express more sorrow, regret and apology than you may ever know, or can believe," for all the things that went wrong.

"There will not be a day of my life where I do not relive and rethink what happened," Blair said. "People ask me why I spend so much time in the Middle East today. This is why. This why I work on Middle East peace."

Blair insisted that he had provided no "blank check" to Washington, and the 2002 note quickly moved to an assessment of the many difficulties of such a war, including building a political coalition to back it and the "need to commit to Iraq for the long term."

He warned of "unintended consequences," like large numbers of Iraqi civilian casualties or an eruption "of the Arab street."

He added: "I did not mislead this country. I made the decision in good faith." And he said the world was a safer place without Saddam, whom he labeled "a wellspring of terror."

Blair stressed Wednesday that the report concluded that he had not invented or distorted intelligence.

But an intelligence official, Tim Dowse, told the committee that British officials were nervous enough about U.S. suspicions that aluminum tubes acquired by Saddam could be used in centrifuges to enrich uranium that they had initially kept the subject out of a British summary of Iraq's weapons projects published in 2002.

After Vice President Dick Cheney had talked about the tubes on U.S. television, "we felt that it would look odd if we said nothing on the subject," Dowse said. "It would open us up to questions."

So the report mentioned the tubes but noted "we couldn't confirm that they were intended for a nuclear program."

Such questions about the prewar intelligence were left unresolved despite Blair's oft-repeated desire for a "smoking gun."

War's legality

In the report, Chilcot refrained from saying whether the 2003 invasion was legal and didn't accuse Blair of deliberately misleading the public or Parliament. But he said that "the circumstances in which it was decided that there was a legal basis for U.K. military action were far from satisfactory."

Peter Goldsmith, Britain's attorney general at the time, initially advised the invasion would be illegal without a U.N. Security Council resolution, but changed his mind shortly before war began. Chilcot said Goldsmith's reasoning was not properly examined at the time by the government.

Relatives of soldiers killed in the conflict said they hadn't ruled out legal action.

"All options are open," said Matthew Jury, a lawyer for some of the families.

Family members who were shown the report three hours before it was published said "we must use this report to make sure all parts of the Iraq fiasco are never repeated again."

"Never again must so many mistakes be allowed to sacrifice British lives and lead to the destruction of a country for no positive end," a group of families said in a statement.

Sarah O'Connor, whose airman brother died in a plane crash in Iraq in 2005, branded Blair "the world's worst terrorist."

The inquiry was set up in 2009 by Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who was under pressure for a public accounting of the conflict. Chilcot and his panel heard from 150 witnesses and analyzed 150,000 documents, but the report has been repeatedly delayed, in part by wrangling over the inclusion of classified material.

A U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee investigation a decade ago found prewar intelligence failings and concluded that politicians had overstated the evidence for weapons of mass destruction and ignored warnings about the violence that could follow an invasion.

Chilcot's report found similar failings. It said Blair's government presented an assessment of the threat posed by Saddam's weapons with "certainty that was not justified."

Information for this article was contributed by Steven Erlanger, David E. Sanger and Stephen Castle of The New York Times and by Jill Lawless, Danica Kirka, Adela Suliman, Mohammed Kaftan, Dominique Soguel, Jim Heinz, Pablo Gorondi and Jovana Gec of The Associated Press.

A Section on 07/07/2016