The Upper West Side of New York has a lot of things to offer the seeker of culture, but ample exhibit space at the American Folk Art Museum at W. 66th Street and Columbus Avenue isn't one of them. The museum has a huge collection of more than 7,000 artworks dating from the 18th century to the present, but at any given time only a minuscule number of them are on display in the museum's modest gallery space.

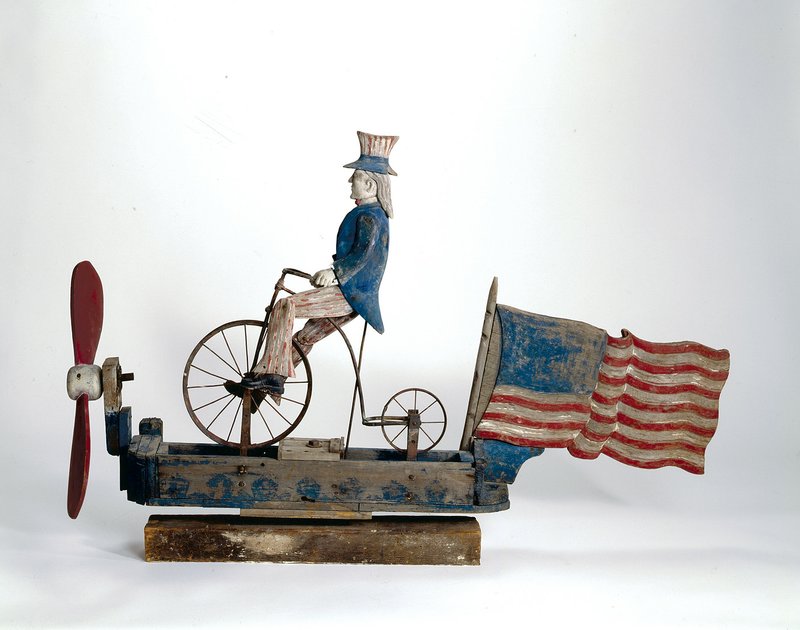

Square footage isn't nearly as limited at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville. That's where a newly opened exhibition titled American Made: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum dedicates room after room to a show of 115 ordinary yet extraordinary handmade pieces that enhanced daily life in the U.S. throughout the past two centuries. America, it seems, is a nation of makers.

It's the first exhibition of folk art, also known as self-taught art, at Crystal Bridges. And for those who have been to the American Folk Art Museum and think they've seen all they need to see there, be aware that Folk Art Museum deputy director and chief curator Stacy Hollander was careful to choose works that are seldom displayed.

"We are dedicated to reaching new audiences and having them discover the beauty and power of folk art to testify, inspire, move and inform from a perspective that is unique in American art," she said.

America's alternative art history goes back to the earliest years of America's formation, Ms. Hollander explained; the exhibit opens with creative tavern signs (these, along with shop signs that illustrated what might be found inside, were used to aid those who were illiterate), a brilliantly colored flag quilt, and a detailed needlework picture with dogs, birds, flowers and folks (created by a 12-year-old named Sallie Hathaway in 1794).

There's a weather vane that was probably made in Paul Revere's Boston foundry in the late 1700s, and a charming trinket box to hold odds and ends made between 1820-1840.

An important form of art in early America was portraiture, Ms. Hollander explained. The portraits reflected the subject's level of attainment and success through clothing, jewelry, furnishings, and books. Traveling portrait painters charged on a graduated scale depending on the amount of detail desired. Even when photography started to appear around 1840, paintings continued to offer color and scale that those new-fangled photos lacked.

Visitors will see furniture, chests and tables decorated with watercolor, ink and pencil, a luxurious appliqued carpet with multiple floral borders, hooked rugs, scrimshaw, prettily decorated love notes (romantic love was accepted as a requirement for marriage by 1830) and embellished documents of birth certificates, deeds and rewards of merit. Near the exit is a more recent entry, a graceful carousel horse from 1914-era Coney Island made of painted wood with glass eyes and a genuine horsehair tail, that practically begs a viewer to climb aboard.

It's unclear why centuries of Americans chose to reveal their creativity and resourcefulness in creating functional, practical items, but they did, and the results are all around us. And, thanks to the vast expanse that is Crystal Bridges, this generous display more than adequately complements the museum's paintings and sculptures while adding to the story of early American culture and identity.

Editorial on 07/07/2016