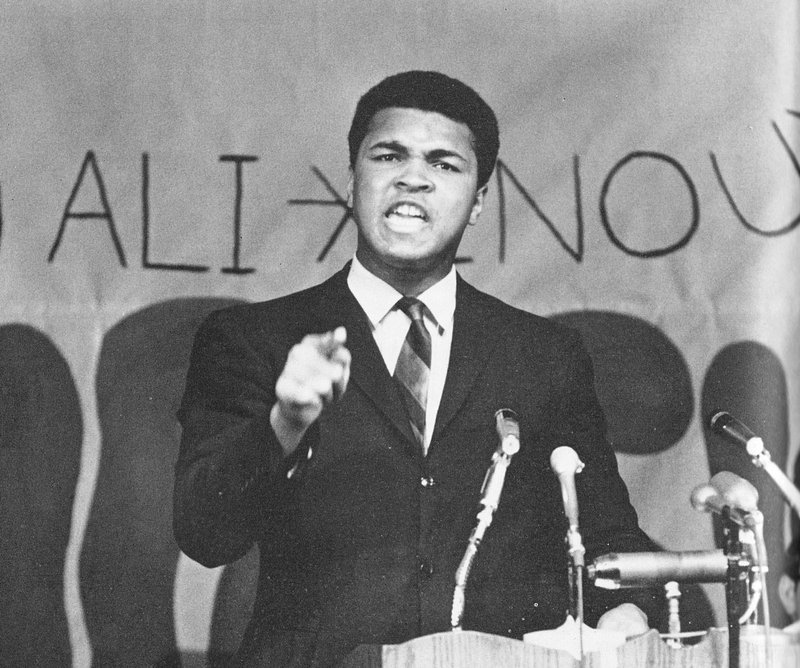

Muhammad Ali was a controversial figure at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville in 1969, but a March 12 speech that year to 4,700 students at Barnhill Fieldhouse drew more criticism beforehand than afterward.

Ali's speech was opposed by the state Senate, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Pulaski Business Men's Association and at least two American Legion posts, according to an article in the Arkansas Gazette.

The speech, in which Ali advocated racial separation and sympathy with some lynchers, was almost anticlimactic in comparison to the tempest that preceded it, newspaper articles indicate.

Milt Earnhart, 98, of Fort Smith said it's time to let the former heavyweight boxing champion rest in peace.

"He had a rough time in life so we just say 'God rest his soul,'" said Earnhart, referring to Ali's battle with Parkinson's disease.

Ali died Friday at age 74. Funeral services will be held for him today and Friday in his hometown of Louisville, Ky.

In February of 1969, Earnhart, then a state senator, introduced a resolution opposing Ali's speech. It passed on a voice vote in the Senate but didn't deter the university from hosting Ali's appearance on campus.

Earnhart said Wednesday that he filed the bill because Ali -- citing his black Muslim religious beliefs -- had dodged the draft during the Vietnam War. Earnhart spent four years in the Army during World War II and served in Germany.

"That's what I was thinking about when I proposed the resolution," said Earnhart, who said he moved to Fort Smith in 1950 and became Arkansas' first television weatherman. Later in life, he was an extra in 30 television shows, including one of the last episodes of ER.

In letters during the 1969 controversy, Earnhart also wrote that Ali was "encouraged by Communists."

When asked if, in retrospect, he still would have filed the resolution, Earnhart said he wasn't sure.

"Everybody was kind of mad at Cassius Clay at that time," Earnhart said. "Time marches on."

Earnhart said Parkinson's disease "took all the joy" out of Ali's life for the past 20 years or so. Ali was diagnosed with the disease in 1984. He died of septic shock because of unspecified natural causes.

A Muslim funeral prayer service will be held for Ali today. The official funeral is scheduled for Friday. Both are open to the public and will be held in Louisville, Ky.

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., Ali changed his name to Muhammad Ali when he joined the Nation of Islam, which believes in the innate superiority of blacks over whites. The Southern Poverty Law Center classifies the Nation of Islam as a hate group, noting that its belief system is rejected by mainstream Muslims.

"We don't hate white people," Ali said in a 1968 interview with a public television station in New York. "I know whites and blacks cannot get along. This is nature. It's getting worse every day."

On April 28, 1967, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces. Two months later, he was convicted of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years. Ali appealed and remained out of prison until the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in 1971.

Since he was barred from boxing professionally, Ali was speaking at college campuses in 1969 and included Fayetteville on his list of stops.

In his UA speech, Ali advocated racial separation and an understanding of George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama.

According to an article two days later in the Arkansas Gazette, Ali said his Muslim religion believed in "racial purity" and forbid intermarriage with other races.

According to the article, Ali "said he had respect for whites in the South for lynching Negroes who bothered their women and pleaded that Negroes protect Negro women."

Ali made a similar comment to Playboy magazine in 1975, saying any man -- regardless of race -- should die for "showing disrespect" to a woman of the black Muslim faith, officially known as the Nation of Islam.

"Put a hand on a Muslim sister and you are to die," Ali told Playboy.

On March 12, 1969, Ali shared the stage in Fayetteville with Floyd McKissick, former director of the Congress on Racial Equality.

According to the Gazette article by Dick Allen, Ali told the audience in Fayetteville that he understood Wallace, who "just tells the truth" about some things.

Ali told the crowd that the Nation of Islam wanted land for its own separate nation, according to an article in the Arkansas Traveler, the university's student newspaper.

"Wallace is, I'm sure, all for our separation plan," the Traveler reported Ali as saying. "I'd like to meet him someday and shake his hand."

Gerald Jordan, an associate professor of journalism at the university, said he remembers Ali's speech in Fayetteville.

"What I remember is Ali's message was not necessarily vitriolic," Jordan said. "I don't remember it being the street-corner Nation of Islam preaching. The guy was charismatic beyond belief, not in a way that was off-putting or dangerous, but just friendly."

Metro on 06/09/2016