A friend of mine recently watched Blazing Saddles with his 14-year-old daughter. It did not go the way he expected. He thought he was introducing her to a classic comedy, a movie that some people believe is the funniest ever made.

She found it problematic, full of racial stereotypes, sexist tropes and inappropriate language.

"How can they use that word?" she asked about the word that most white people know never to pronounce, even if they end it with an "a" rather than "er."

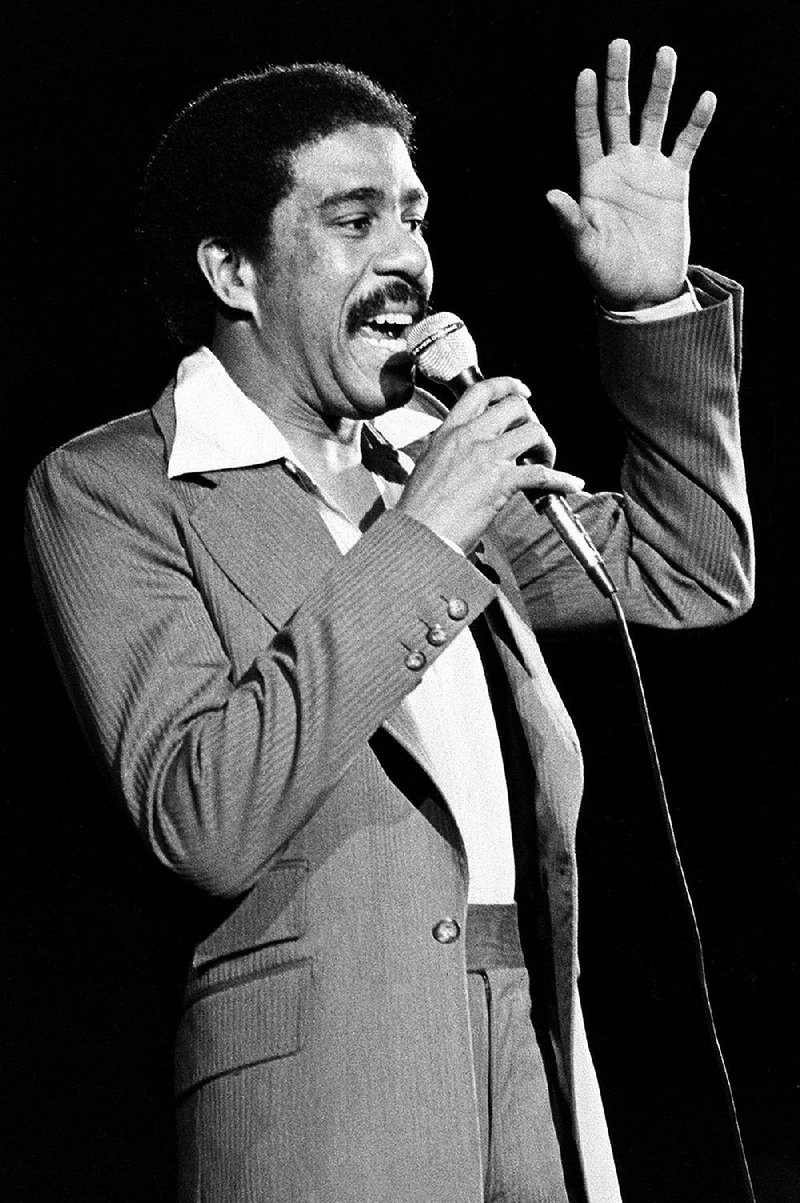

He tried to explain it to her, pointing out that one of the writers on the film was Richard Pryor, a profound comic who happened to be a black man who had grown up in a whorehouse in Peoria, Ill. At the start of the 1970s, Pryor decided to denature the word my friend's daughter found offensive, that had caused so many people to feel hurt and shame. In his autobiography Pryor Convictions he wrote:

"And so this one night I decided to make it my own. Nigger. I decided to take the sting out of it. Nigger. As if saying it over and over again would numb me and everybody else to its wretchedness. Nigger. Said it over and over like a preacher singing hallelujah."

And we know how that went.

"It changed me, yes it did," Pryor wrote. "It gave me strength, let me rise above ... "

His embrace of the word bothered some people. He was challenged about it again and again. In 1979, when Barbara Walters interviewed him, she noted that the word made her uncomfortable, partly because he could say it and she couldn't.

"You just said it," Pryor shot back. "You said it pretty good. That's not the first time you said it."

But by October 1980, he'd sworn it off. When Ebony magazine asked him why, he told them: "I took a trip to Africa ... I went to Kenya, and while I was there something inside of me said, 'Look around you, Richard. What do you see?' I saw people. African people. I saw people from other countries, too, and they were all kinds of colors, but I didn't see any 'niggers.' I didn't see any there because there are no 'niggers' in Africa. Can you imagine going out into the bush and walking up to a Masai and 'Hey nigger. Come here!?' You couldn't do that because Masai are not 'niggers.' There are no 'niggers' in Africa, and there are no 'niggers' here in America either. We black people are not 'niggers,' and I will forever refuse to be one."

When Ebony followed up, asking Pryor how he would respond to "people who say that you used those words on stage and on your albums and got rich doing it," he responded: "I'd say to 'Allow me to grow.'"

I don't know that we ought to make studying evolution of Richard Pryor a prerequisite to the viewing of Blazing Saddles, but we might all take notice of the fact that works of art are always products of the time in which they are produced. One of the great things about Blazing Saddles is its implicit critique of American racial attitudes and Hollywood's whitewashing of history via Western mythologies. One way to look at Blazing Saddles is that it is a movie about white flight.

The absurdist plot is set on the American frontier in 1874, where the villainous Hedley Lamarr (Harvey Korman) schemes to depress the property values of an all-white town called Rock Ridge, where all the residents share the surname Johnson, so that he can buy the land for cheap. (He knows the railroad is coming to the town.) He figures the best way to get the townspeople to abandon their property is to appoint black railroad worker Bart (Cleavon Little) as sheriff. Because if you put a black person in a prominent municipal position, the white folk will naturally leave, right?

Another thing we ought to remember is that Blazing Saddles appeared less than 10 years after the Civil Rights Act, and only six years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. School busing to achieve integration and affirmative action were hot-button topics. (Late in the film, after Lamarr's initial plan has failed and Bart has been accepted as the townspeople's champion, we catch a glimpse of a poster that reads: "Help Wanted: Heartless Villains For Destruction of Rock Ridge, $100 Per Day, Criminal Record Required, Hedley Lamarr, Equal Opportunity Employer.")

The racial critique of Blazing Saddles mightn't be the most remarkable thing about it -- it's a postmodern film with a Borscht Belt sensibility that marries the silly to the sublime. From the opening scene, when railroad workers charged with singing an old spiritual like they sang when they were slaves break into a sophisticated, anachronistic rendition of Cole Porter's "I Get a Kick Out of You," to the ending where Bart pursues Lamarr off the set of the movie and into Grauman's Chinese Theatre (where they're showing the movie he's acting in) where he watches himself ride off into the sunset (then get into a stretch limo) Blazing Saddles keeps folding back on itself, a series of jokes within jokes.

In this context, is it really so important that some of the characters use the N-word?

People use the N-word in real life, sometimes playfully, sometimes to provoke, and sometimes to denigrate. It is an ugly word, but ugly words can sometimes be employed in helpful ways. An artist might find a reason to show us the worst things about ourselves; if one means to represent the world, one is compelled to take notice of ugliness. Just because a word can be used in a certain context does not mean that we are all licensed to say whatever we want whenever we want to whoever we want. We are all allowed to grow.

And people will say that because of political correctness, a movie like Blazing Saddles could not be made today. But it's not political correctness that would keep Blazing Saddles from being made, it's that certain dynamics have shifted and there are things that we don't find so funny anymore.

My friend's 14-year-old daughter doesn't hear the N-word the same way audiences heard it in 1974 -- and good for her. It's not shocking or funny to her, it's simply rude.

That she doesn't find Blazing Saddles particularly funny might even represent a kind of progress.

But ...

There's danger in applying contemporary standards to works done decades or centuries ago. Animal House turned 40 years old last weekend, and some people decided that was a good occasion to signal their virtue by declaring it a very bad, not good at all movie that celebrated alcoholism and sexual abuse. (Of course it did -- it was a movie about college-age males of privilege in the presumably innocent, pre-JFK-assassination '60s.) What is missing from revisionist critiques of Animal House seems to be any awareness that the filmmakers understood they were making a satire.

While Animal House is no Blazing Saddles, it is still a very funny, very smart movie. While it depicts college-age men doing horrible stuff, I'm not sure anyone should take it as an endorsement of sexist, homophobic or racist behavior. I'm not sure that anyone should look to the entitled white male characters in Animal House as models of how to live.

Yet I know people who did. Animal House came out when I was in college. Lots of guys I knew modeled themselves on Tim Matheson's Otter character. It inspired toga parties. Maybe it inspired a lot of binge drinking and boorishness. I might argue that one of the scenes that people are now finding most offensive -- the Deltas' sortie to a black club to see their beloved Otis Day and the Knights is a pretty shrewd parable about cultural appropriation (the Deltas, especially Boon, are looking to borrow the cool of their favorite bar band). And sure, the line about "primitive cultures" lands wrong today -- it wasn't funny in 1978 either -- but if you allow comedy to be transgressive you're going to experience moments when you involuntarily cringe.

We should understand that there are people who are suggestible; who, despite all warning, will try out dangerous behaviors at home. I don't know what we can do about them except patch them up or bury them, use their stories to demonstrate the types of idiocy to which our kind is susceptible. But do we really have to explain that one should not pose as the boyfriend of a recently deceased woman in an attempt to score with her roommate? Or that Bluto's voyeurism is pathetic and creepy? The only moral one should take from Animal House is Dean Wormer's observation that "fat, drunk and stupid is no way to go through life, son."

The cynicism that the movie depicts is the cynicism that is in the world. I don't think Animal House endorses the idea that a man like John Blutarski could go on to have a successful political career or that the nihilists of Delta House escaped any serious consequences from their behavior as undergraduates. Director John Landis and writers Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney and Chris Miller simply observed that this was the case. Lots of entitled behavior gets excused in this country, the guilty are not always brought to justice.

I suppose we could hold artists from past generations to modern standards -- and that some people try to do just that, attaching trigger warnings to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or taking Laura Ingalls Wilder's name off a children's literature award because her Little House on the Prairie books portray "insensitive" attitudes. Insensitive attitudes exist, and even humanists like Huck Finn are prisoners of their upbringing and customization. For Wilder to have pretended otherwise would have been a betrayal of her historical fiction; it would have cheapened and romanticized the world she meant to portray.

I'm not a fan of Wilder -- I didn't read her growing up -- and I'm not sure that naming awards after human beings is all that important anyway. But how could we possibly expect a woman writing in the 1930s about the 1870s to conform to modern "values of inclusiveness, integrity and respect, and responsiveness?"

None of us knows how history will judge us, or which of our deeply held beliefs might turn out to have been misconceptions. Maybe all we can hope is our mistakes inform us, and that we are allowed the chance to grow.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/05/2018