Less wealth among millennials is driving an increase in renting homes and a decrease in buying them, experts say.

Since 2010, the share of homes owned by their occupants has shrunk nationwide and in Arkansas, according to U.S. Census Bureau data released today.

Rents are up, wages are stagnant and the cost of going to college or getting an education beyond high school is more and more cumbersome, experts told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Further, people stung by the implosion of the housing market, which continued after 2010, may be wary of ever buying homes again, said Mervin Jebaraj, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

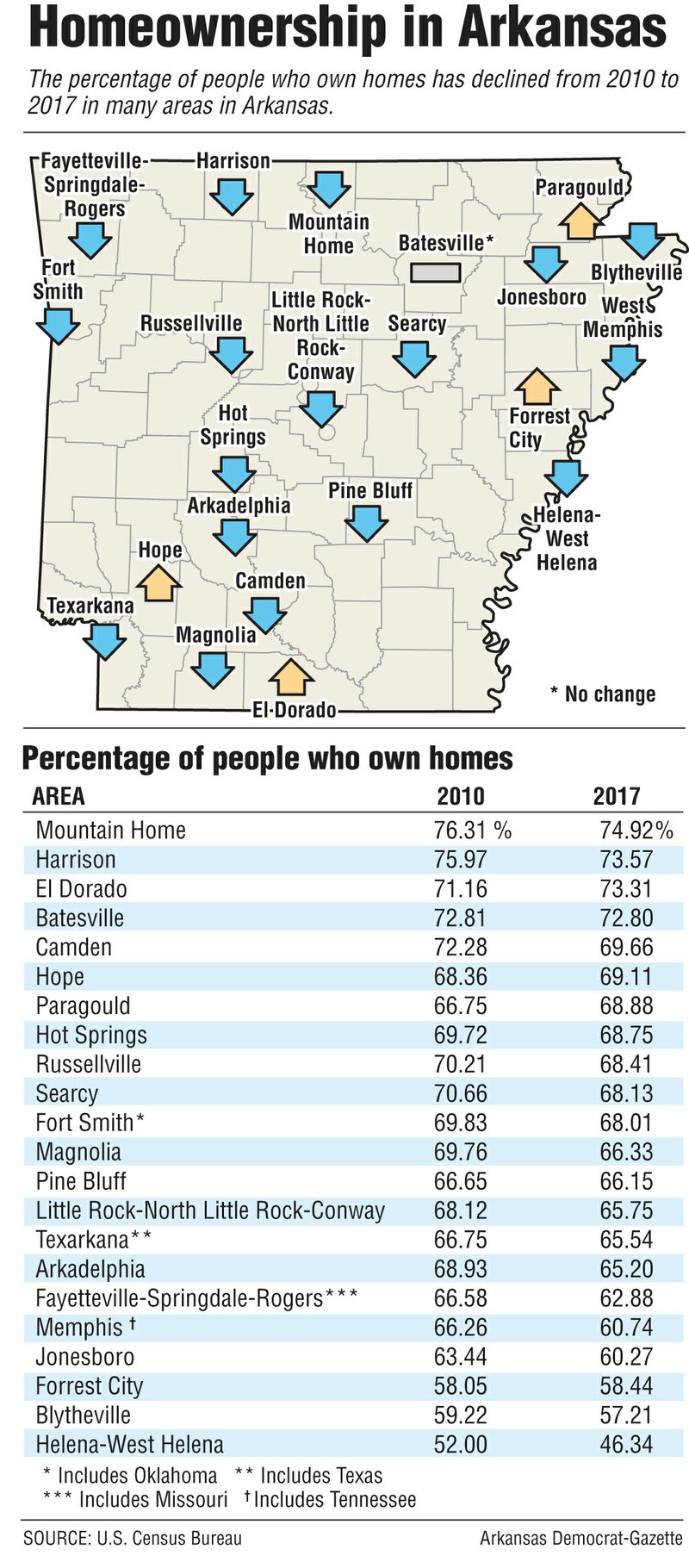

Homeownership rates in most of Arkansas' metropolitan and micropolitan areas have declined since 2010, the census data show. Micropolitan areas have urban cores of at least 10,000 people but fewer than 50,000 people. Malvern became a micropolitan area after the 2010 census.

Of the 22 areas that the census's American Community Survey measured in 2010 and 2017, only four saw upticks in homeownership -- micropolitan areas Paragould, El Dorado, Hope and Forrest City.

Bigger areas with higher population growth -- such as Northwest Arkansas and Jonesboro (including Poinsett and Craighead counties) -- had some of the biggest drops in homeownership rates in the state, the data show.

That's because of the lack of wealth among younger residents and the lack of affordable properties in those areas, Jebaraj said.

"It's pushing on both ends," he said.

Millennials -- people born between 1981 and 1996 -- are earning less than previous generations did at their age, Jebaraj said.

"There's not a whole lot of money to put towards a house," he said.

Homes are too expensive for younger people to buy in Northwest Arkansas, the economist said. People likely face paying far more than 30 percent of their household income on homes, he said. Thirty percent of income is generally considered the maximum home-affordability level.

The Fayetteville-Springdale metropolitan area, which stretches from Washington County into Benton and Madison counties, and Missouri, had a 62.9 percent homeownership rate in 2017, down from 66.6 percent in 2010.

The average price of a home in Benton and Washington counties was $240,659 and $230,210, respectively, in September, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette previously reported. In October 2010, those average home prices were $169,783 and $147,079, the newspaper reported then.

Those price increases fall short of being attributed to inflation. Inflation would put current home prices at less than $200,000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index inflation calculator.

The American Community Survey five-year estimates put median household income in the Fayetteville-Springdale metropolitan area at $53,207 in 2017, up from $46,021 in 2010. That's a 15.6 percent increase, while home prices leapt 41.7 percent in Benton County and 56.5 percent in Washington County during that time.

The next-most-expensive average home price is in Pulaski County, at $189,716 in September, up only $4,135 from October 2010. The Little Rock-North Little Rock-Conway metropolitan area's homeownership rate declined from 68.1 percent in 2010 to 65.8 percent in 2017.

Elsewhere, homeownership rates have declined in places where it's not necessarily more expensive to live.

Homes in Arkadelphia are older, with no recent updates, and subsequently are often overpriced, said Jason Edington, a real estate agent with United Country Crystal Lakes Realtors. There, homeownership has dropped 3.7 percentage points since 2010, from 68.9 percent to 65.2 percent.

Rents are so high now that students and young people -- whom Edington says are more frugal than his generation, Generation X -- are likely not saving as much as they need to be to afford down payments. Parents are more often buying homes and then renting them to their children while they attend college in Arkadelphia, he said.

"We need more jobs," Edington said. "If you had more jobs and good-paying jobs, then you would see a difference in people buying more houses."

Edington said he hopes that the proposed Shandong Sun Paper mill in Arkadelphia, a $1.8 billion investment by a Chinese company, generates the kind of job growth the area needs and that it's not the only investment someone makes in the city.

Homeownership in Forrest City has mostly remained steady at about 58 percent, despite economic hardships, something real estate agent Kelly Lewis said is the result of flipped houses and increased use of federal rural development loans. Such loans have lower interest rates and don't require down payments.

"Everybody I see I ask them if they want buy a house," she said, "and I sell a lot of houses that way."

In Paragould, the homeownership rate has risen 2.1 percentage points since 2010, from 66.8 percent to 68.9 percent.

Homes in Paragould have become more affordable with an increase in manufacturing jobs and work in other sectors that don't require as much education and, therefore, as much student debt, said Sue McGowan, CEO of the Paragould Chamber of Commerce. Further, a lot of the companies in town pay for their employees to go to school or training for career advancement, she said.

In recent years, American Rail Car Industries, Anchor Packaging and Tenneco, to name a few, have expanded, McGowan said. So has GW Communications, a telecommunications company, and various medical industry jobs have opened up, she said.

In places that are competing instead for a knowledge-based economy, like Northwest Arkansas and other urban areas, student debt is holding many young people back, officials said.

One way to make homes more affordable is to build more homes, Jebaraj said.

"If you build a lot more housing, especially in places where people want them, you can push prices down," he said.

That's the most straightforward solution he can think of, he said, "not that it's particularly easy to accomplish."

Leaders also need to figure out why millennials don't have as much wealth and fix it, he said, but he noted that addressing student loan debt has proved to be "contentious."

Information for this article was contributed by David Smith of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

A Section on 12/06/2018