Paxton Allen is shaking his head from side to side, and looks like he's just about ready to pitch a fit.

It's understandable. Paxton has been here at Arkansas Children's Hospital since he was born five months ago with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which means that the left side of his heart is too small.

He is connected to beeping, blinking monitors and a cannula that sends oxygen flowing through his nostrils, although it keeps coming out. His little chest still shows the incision from where doctors recently performed a second surgery on his heart.

He has been on life support, had four strokes, seizures and a collapsed left lung, but he has defied expectations, says his mother, Nikita Allen of Glenwood.

"They told me he would never take a bottle, but he took 15 milliliters from the first bottle he ever had at 2 months old," she says. "The doctor said he gained weight more than any hypoplastic child she had ever seen, so that led us to this second surgery sooner than he needed it."

Right now, though, with his room in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit filling with strangers, his head is in constant motion as if he is saying, "No, no, no."

But then he hears Andrew Ghrayeb's softly strummed guitar.

Paxton becomes completely still and is transfixed as Ghrayeb sings sweetly:

"Hello, Paxton/It's good to see you/Hello, Paxton/It's good to see you ..."

Ghrayeb is the hospital's music therapist, and has been seeing Paxton for a couple of months now, strumming his guitar, singing and giving the baby little instruments like rattles and maracas so he can play along.

"He's doing much more in terms of actually being aware of his environment and actually shaking the rattle, tracking what I'm doing and making eye contact," Ghrayeb says as Paxton watches closely.

"They were worried about him not being able to use his hands," Allen says. "This gives him the opportunity to not only enjoy music but to do some physical therapy, too. We push for Andrew more than any of it. This is [Paxton's] favorite, you can tell. Watch, he'll start smiling at him."

And he does.

. . .

Ghrayeb, 34, is the hospital's first and only music therapist, and one of just a few in the state.

He grew up near Philadelphia, started playing piano at 7 and later learned saxophone and guitar. He eventually began writing songs and playing in bands.

Ghrayeb earned a degree in music business and was working at a financial company when he realized that he wanted to get into counseling.

He looked into graduate programs at Immaculata University in Philadelphia and discovered something that struck a chord. Music therapy.

"That was where it started," the soft-spoken Ghrayeb says during an interview in the hospital's coffee shop last month.

The pull of a music therapy career, he says, came from "wanting to help people and also use the musical skills I've developed over the years, and being able to work with a lot of underserved populations."

He was hired at Children's in 2014 by Renee Hunte, director of the hospital's Child Life and Education department, who saw the results of music therapy when she worked at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and at Children's Medical Center of Dallas, and wanted a program here.

With encouragement from Children's CEO Marcella Doderer and help from fundraiser Sharon Bale, Hunte began the search that eventually took Ghrayeb to Little Rock.

"Andrew is a breath of fresh air," she says. "He is very passionate about what he does, and he cares for the patients and their families. He makes the patient experience that much more richer for them and their families."

Funding for the program was secured through donations, and Ghrayeb's services are free for patients. The Child Life and Education department also includes child life specialists, artists in residence, teachers and other staff.

. . .

Dr. Oliver Sacks, the late neurologist and author of, among other titles, Awakenings, said, "I regard music therapy as a great power in many neurological disorders -- Parkinson's and Alzheimer's -- because of its unique capacity to organize cerebral function when it has been damaged."

Ghrayeb describes what he does as "using music for nonmusical goals."

"To the outsider, they see us and it looks like we're just playing, but it is so much more than that," he says.

There are neurological aspects to music therapy, like working with patients with brain injuries to relearn how to communicate. Often if they can't speak, they can sing, Ghrayeb says.

"I use music to work on that and work on breathing, breath support and everything that goes into speaking to hopefully find a new neural pathway."

Playing instruments, even if it's simply hitting a xylophone with mallets, helps patients develop fine-motor skills.

Then there are patients for which music therapy aids in self-expression.

"If someone has had a loss we might use songwriting to help address that," he says. "When you're working with kids, especially adolescents who might not have the emotional maturity to sit down and talk, they tell you a whole lot through their music. That's a good start."

One patient Ghrayeb worked with was a 10-year-old who liked writing his own songs, so Ghrayeb brought recording equipment to his sessions.

"I was able to bring the studio to him, put the headphones on and take him out of that room a little bit," he says.

Sessions are interactive, with Ghrayeb and patient making music together, though sometimes it's not possible.

"Primarily we like to make the experience about actively playing music together," he says. "But I've had patients who are quadriplegic, so then we'll listen to music together, pick out a few lyrics and do lyric analysis and talk about what that means to them."

. . .

McKendalyn Martines of Paris was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis when she was 10 months old. It was during a stay at Children's a few years ago that she started music therapy with Ghrayeb.

"It was awkward at first," the 17-year-old high school senior says. "I'm shy, but he grew on me, and I think I grew on him."

Recalling their first session, Ghrayeb says, "I asked her what kind of music she liked and she said, 'Conway Twitty.' I was not expecting that."

He taught McKendalyn how to play the ukulele, and now she has three of her own.

As a CF patient, she was often in a room alone to avoid catching other illnesses. Music therapy was a bright spot during her hospital stays.

"Even though we would only have an hour, it was the best hour," she says. "If I had a ukulele there I could practice after he left, and I'd still be practicing when he got there the next day."

Kristen Harderson, whose 4-year-old son, Cooper Hunt, got a heart transplant July 12 at Children's, says music therapy was a pleasant surprise.

"We didn't even know it existed, but Andrew came by and told us all about it and Cooper fell in love with the whole program," she says after a recent checkup. "Cooper loves Beatles songs, so Andrew learned a bunch of Beatles songs for him."

Ghrayeb would show up with his guitar and a cart filled with maracas, bongo drums, keyboards, rain sticks and other instruments.

Cooper had trouble walking, Harderson says, and Ghrayeb would help him to the bedside.

"It helped him move a lot more. Andrew even got him on the floor to play a really tall drum. We did the art therapy, too, and that was awesome. Our walls were covered with art."

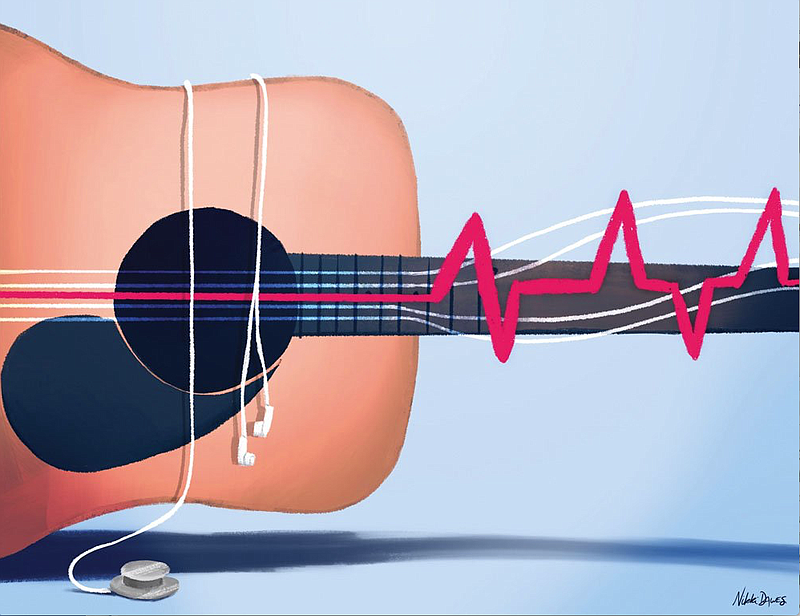

Arkansas Children's Hospital music therapist Andrew Ghrayeb created this version of Andrew Gorkey's "Masterpiece" using guitar and a recording of Paxton Allen's heartbeat. Paxton, who is five months old, is a patient at the hospital and is part of the music therapy program there.

Versions of The Beatles' "All You Need Is Love" and "Yellow Submarine" were made by music therapist Andrew Ghrayeb using the heartbeat of Arkansas Children's Hospital patient Cooper Harderson, who had a heart transplant earlier this year. "All You Need is Love" features his old heart, while his new heart beats beneath "Yellow Submarine."

. . .

What is it about music that makes it so useful in therapy?

"On a strictly neurological level, music affects our brain in a different way than you and me just talking," Ghrayeb says. "If we were playing music together -- singing, anything like that -- it looks different if you were to do an MRI of your brain. It lights up both hemispheres of your brain. We attach so many memories and emotions to different songs, and music helps us connect. I think that's why it's such a unique medium for therapy."

Laura Hobart-Porter, a pediatric rehab doctor at Children's, says the music therapy her patients get with Ghrayeb allows her "to have an entirely additional set of tools at my disposal. It really enhances the way I'm able to treat my patients."

For instance, occupational therapy can be tedious for toddlers and even some teenagers, but incorporating music therapy can help toward reaching the same goal.

"The patients oftentimes don't even realize they're doing something that can functionally help them," Hobart-Porter says. "There are patients I know who would not be where they are today if it weren't for him."

She actually put Ghrayeb to work when he was interviewing for the job.

"There was a girl who was bedridden because she had so much pain. She couldn't move, she couldn't speak. On a hunch, I asked if he could work with her and play some tunes. It was like turning on a light switch. She was completely shut down. Andrew works with her for a week and all of a sudden she's walking, talking and doing things for herself."

Ghrayeb shares with doctors what he learns during sessions with patients.

"He has an amazing understanding of the neuroscience behind music," Hobart-Porter says. "He will come to team meetings we have on the rehab unit and he will talk about the neuroscience behind everything he does. It's informative for the therapist and the families, but it also reminds me that he's paying attention to the goals I'm trying to achieve for the patient."

. . .

You hear the heartbeat first, a faint, 'wump, wump, wump' and then the opening notes of The Beatles' "All You Need Is Love" played by Ghrayeb on acoustic guitar.

The heart belongs to Cooper. It's the one he was born with, but no longer has.

The song ends and segues into another Beatles tune, "Yellow Submarine." The heartbeat keeping time on this one is Cooper's new heart, the one he got in July.

Ghrayeb uses a special stethoscope to record patients' heartbeats and then loops them into a recording he gives to the family.

"It's crazy," Cooper's mother, Harderson says. "You can listen to the old [heart] and listen to the new one and it's completely different."

For the Allens he incorporated Paxton's heartbeat into a version of Christian pop singer Danny Gokey's "Masterpiece" before Paxton's second surgery.

"I picked [that song] because it talks about a heart being broken and how God is making a masterpiece," Nikita Allen says.

. . .

On a good day, Ghrayeb sees 6-10 patients, and does administrative work in his small office that is crammed with instruments.

Hunte hopes to be able to bring in more music therapists.

"We would love to expand," she says. "It would be good for Andrew to have professional colleagues here to bounce ideas off of."

Arkansas, Ghrayeb says, is a bit of a music therapy desert. There were five music therapists at the Philadelphia hospital where he did his internship. The Natural State has just eight accredited by the national certification board.

"I'm part of an Arkansas state task force to try and spread music therapy and make sure it's recognized on a state level," he says. "Our certification is nationally based. Our goal is at some point to have some sort of state recognition."

. . .

In Paxton's room, Ghrayeb is finishing his visit, which wasn't an official therapy session. Paxton, whose heart rate has dropped to 127 beats per minute, is still fixated on the guitar and Ghrayeb's soothing voice.

"Paxton is on a lot of [drugs]. He has been his whole life," says Allen, who has two other children and who alternates with her husband, Josh, on visits with Paxton. "When he's withdrawing, the music soothes him."

Ghrayeb picks gently at the guitar strings. Paxton shakes a little rattle and sneezes.

"I can play in a way that's tailored to stimulation he can handle," he says.

"Yeah. There's no AC/DC," Allen laughs.

Ghrayeb starts to sing:

"Now it's time to say goodbye/Bye-bye Paxton ..."

"They're really fortunate to have music therapy here at this hospital for children," Allen says. "And now we have to wean Paxton from Andrew."

Style on 12/16/2018