One of the things that's admirable about film director Steven Soderbergh is that he keeps a media diary, a running list of all the movies, television shows, books, plays and short stories he consumes each year. And for the past few years, he has been compiling an annual chronological summary and publishing it on his Extension 765 blog (extension765.com).

Seeing how the year isn't quite over, his 2018 list isn't up yet, but you can look back at his 2017 diet. It's intriguing. I wonder -- does Soderbergh list a book on the date he begins it or when he finishes it? Does he only list books he completely finishes or significantly dips into? Does he list every title he cracks open?

A quick count suggests he read 49 books in 2017, which seems like a lot given that he has a lot on his plate. It was an eclectic list -- the first book, P.D. James' The Mistletoe Murders and Other Stories, appears on the list on Jan. 2. (The holiday theme suggests that Soderbergh records his books on the day he finishes them.) There are books that have connections to his day job (Bresson on Bresson, director Carl Reiner's 1993 novel All Kinds of Love, Mike Figgis' The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations, a smattering of nonfiction including Joan Didion's South & West, the latest from Michael Chabon and Haruki Murakami, a couple about animal psychology by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson.

It's the kind of list you'd expect from a smart pop artist who publishes lists of the books he has read.

I don't document my media consumption. Mainly because I can't see any real reason to until I come to an occasion like this, when I would like to be able to definitively tell you how many books I read last year. So you could compare it to the total number of books published (possibly as many as 500,000 in the United States last year) and take that into account when I start to chirp about the "best books" of the year.

My guess is I read -- cover to cover -- a book a week. This is in part because I write a biweekly column about books. But it's also a habit I've had since childhood. I hardly ever go to bed without a book.

I probably start five books for every one I finish. And I put books down for lots of reasons that have nothing to do with their merit. For instance, I started reading Delia Owens' Where the Crawdads Sing (G.P. Putnam's Sons, $27) with every intention of writing about it, when I heard something intriguing about Sigrid Nunez' The Friend (Riverhead, $25), which had just won the National Book Award. So I pulled out The Friend, which had been sitting on my to-get-to pile for nearly a year, read a few pages, and got hooked.

Maybe I'll get to Where the Crawdads Sing eventually. But in the interim, more interesting titles have come in. I'm currently involved in Joyce Carol Oates' 2017 novel A Book of American Martyrs (Ecco/HarperCollins, $29.99), which will probably do me absolutely no good as far as the book column goes since it's nearly 2 years old.

I made a conscious decision not to write about this year's John Grisham book (The Reckoning, Doubleday, $29.95) for the simple reason that I have written about his last two. I read most of Bob Woodward's Fear: Trump in the White House (Simon & Schuster, $30) and a lot of Michelle Obama's Becoming (Crown, $32.50) but I can't imagine that anyone who would be interested in these books needs to hear about them from me.

If my reading seems to be dominated by novels, that's at least in part because I get most of my nonfiction from magazines and newspapers. Twice this year I had the experience of opening David Grann books -- The White Darkness (Doubleday, $20) and the movie tie-in edition of The Old Man and the Gun -- to realize I'd already read the work in The New Yorker.

So, what appears below is definitely not a list of the best books of the year. It's a list of books published in 2018 that I noticed, read, for the most part reviewed and would recommend.

I'm planning on following up with readers' choices and reactions to this list in a couple of weeks. so note the email address at the end.

NOTABLE BOOKS OF 2018

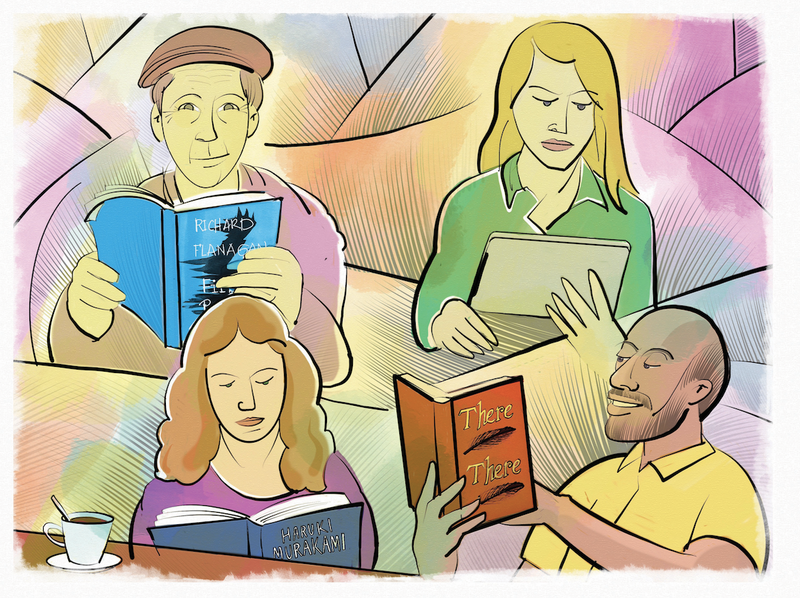

The best place to start is with Haruki Murakami's 14th novel Killing Commendatore (Knopf, $30), a cultural inevitability about which everyone who issues opinions on literary fiction is required to comment. It's quite a good book that verges close to self-parody, as Murakami explores some of the the themes of his professed favorite novel -- F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby -- while diving down familiar rabbit holes. While there is a sense that Murakami is playing his greatest hits with this big book, it's also a work of subtlety and craft that, had Murakami not showed his work in previous books, might be taken for genius.

Tara Westover's Educated: A Memoir (Random House, $28) is showing up on a lot of end-of-the-year lists, and with good reason. It's a timely and remarkably measured critique of the ascendant cult of apocalyptic ignorance and disengagement. Raised in Idaho by survivalist parents who forced their children to work beside them sorting scrap metal and mixing dubious herbal home remedies, Westover was never sent to school but learned to read from the Bible, the book of Mormon and the speeches of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. Still, she manages to escape her blighted home life, finally entering a classroom at the age of 17 (albeit without ever having heard about the Holocaust or Martin Luther King Jr.) and eventually obtains a doctorate from Cambridge University.

First-time novelist Randy Kennedy must have spent a lot of time researching the sparse flora of the region and the Mennonite population in northern Mexico, or maybe he just lived through it, but in any case his Presidio (Touchstone, $26), about a a refusenik of late capitalism living from stolen car to car and off things he burgles from cheap motel rooms in the Texas Panhandle in the early 1970s, was one of the most affecting books I read all year.

I liked Richard Flanagan's latest novel, First Person (Knopf, $26.95), more than most other reviewers. It's a meditation on the nature of storytelling and the corrosive effect of lies, informed by the author's real-life experience with one of the most notorious con artists in Australian history, a man who called himself John Friedrich. It is framed as a memoir, not of the con man (who is called Siegfried Heidl), but of young Tasmanian would-be writer Kif Kehlmann. He is introduced into Heidl's circle by his rough childhood friend Ray, who has become Heidl's stooge and gofer.

Jazz critic Gary Giddins' exhaustive Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star--The War Years, 1940-1946 (Little, Brown, $40) comes 18 years after the publication of Giddins' Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star and continues the obsessive deep dive into one of the 20th century's most intriguing and misapprehended cultural engines. It's hard for a 21st-century audience to understand what Crosby meant, though Tony Bennett got at the crux of it when he said: "Bing taught everyone to relax."

Lorrie Moore's See What Can Be Done: Essays, Criticism, and Commentary (Knopf, $29.95) is a compendium of 60-odd pieces she has published in the New York Review of Books, New Yorker, New York Times Book Review, Atlantic and elsewhere over the years. While I haven't re-read them all, it's one of the few that has earned a place in my dwindling permanent collection -- up there with Updike's Hugging the Shore, Due Considerations and Higher Gossip, Anthony Burgess' Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English Since 1939 and Frank Kermode's The Sense of an Ending on the reference shelf.

Elizabeth H. Winthrop's novel The Mercy Seat (Grove Press, $26) is recommended for the moral weight of its narrative and the calm yet insistent drive of her prose. Evocative of To Kill a Mockingbird, the book narrates events leading up to the quasi-public execution of an 18-year-old accused rapist in 1943 Louisiana. It's based on a couple of horrible true stories. And it resonates.

I've recently written about Robin Robertson's novel-length poem The Long Take (Knopf, $27) and Sigrid Nunez' aforementioned The Friend, so it feels unnecessary to do so again. Nevertheless, if I'm making a list, they should be on it.

So is Jane Leavy's The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created (Harper, $32.50), a popular biography that I'm not sure we really needed (Robert Creamer's 1974 book The Babe: The Legend Comes to Life is the indispensable one) but is fun to read. Leavy's strength is interrogating the way we perceive our sports idols, and she does a good job of exploring the complicated racial intersectionality of Ruth (a dark-skinned man whose heritage was the source of much speculation, especially at the beginning of his career when his nickname was a racist epithet).

On the other side of the spectrum, my old friend Howard Rosenberg has turned his attention to another baseball figure, one much better known than his previous subject Cap Anson, and delivered the comparatively breezy single-volume Ty Cobb Unleashed: The Definitive Counter-Biography of the Chastened Racist (Tile Books, $32).

Rosenberg, as much as possible, assays the myths surrounding Cobb and returns a portrait of a man of his time as well as a useful and insightful critique into the literature surrounding him. The author has not only produced his own scrupulously sourced biography -- he fact-checked all the other major biographies of Cobb since 1961's My Life in Baseball, Cobb's autobiography written with sportswriter Al Stump (whose 1994 book Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball was the basis for Ron Shelton's 1994 movie that starred Tommy Lee Jones).

It's impressive if too detailed (and even-handed) for the casual fan.

Mark Di Ionno, a newspaper columnist for the New Jersey Star-Ledger, has, with Gods of Wood and Stone (Touchstone, $26) written a fascinating baseball novel, in which is embedded a fierce and thoughtful critique of our popular culture.

A couple of interesting looks at our criminal justice-industrial complex crossed my desk. Fox Butterfield's In My Father's House: A New View of How Crime Runs in the Family (Knopf, $26.95) caused me to think about "crime families" in a different light, while Tim Tolka's Blue Mafia: Police Brutality & Consent Decrees (Polity, $12) is a journalistically meticulous look at two federal investigations into local police misconduct in the small Ohio towns of Steubenville and Warren that feels remarkably timely.

More novels, as my space/time continuum begins to run out: Alan Hollinghurst's The Sparsholt Affair (Knopf, $28.95), a meticulously plotted book that spans seven decades, beginning with a vivid evocation of Oxford during World War II. Hallgrimur Helgason's inspired-by-a-true story Woman at 1,000 Degrees (translated by Brian Fitz Gibbon, Algonquin Books, $27.95); Stephen Markley's Ohio (Simon & Schuster, $27), and -- as a kind of companion piece -- Nico Walker's largely Cleveland-set Cherry (Knopf, $26.95), a remarkably funny vision of opioid heartbreak.

Two more first novels: Tommy Orange's There There (Knopf, $25.95) and Talley English's Horse (Knopf, $26.95).

Finally, while I'm not much of a fan of fiction that apes the cinematic experience -- I look to movies and books for different things -- Jonathan Ames' novella You Were Never Really Here feels as remarkable as the acclaimed Lynne Ramsay film (starring Joaquin Phoenix) that was made from it. I read it in one sitting, taking about as much time as it does to watch the film.

I could go on -- and I will.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 12/23/2018