We all know the feeling. You're at a restaurant deciding what to order when you start to wonder about a description on the menu. You might subtly Google it, or maybe you're bold enough to ask the waiter what that thing means. But chances are, you just move on to something you recognize and order it instead.

Perhaps the source of your confusion was Washington restaurant Siren's Alaskan halibut with "mishmish spiced octopus" and "sobrassada emulsion," or rabbit rillette with "kasteel rouge mustard" and "kampote peppercorn" from Washington-area restaurant Flamant. Or maybe it was Ana at District Winery's "pommes paillasson."

The use of French terminology may not have seemed like a total gamble for Ana's menu-writers -- after all, plenty of us have heard of pommes frites and can guess that the dish would contain some kind of potato. Still, it wasn't a decision they made lightly: A committee of restaurant staff toyed around with such possibilities as "Lincoln latkes" and "dreamy potatoes" to describe the dish, which consists of potatoes that been shaved into clarified butter, then cooked, pressed, chilled and fried.

But those names all sounded too kitschy for what's essentially fried potato sticks. "This was an extensive conversation ... for what is really elegant tater tots," general manager Sean Alves said.

Anything with "tater tots" in the name could catch people's attention, but in the end, the team felt "pommes paillasson," the traditional French name for the grated potatoes, was actually the most straightforward.

Do most diners even know what that means?

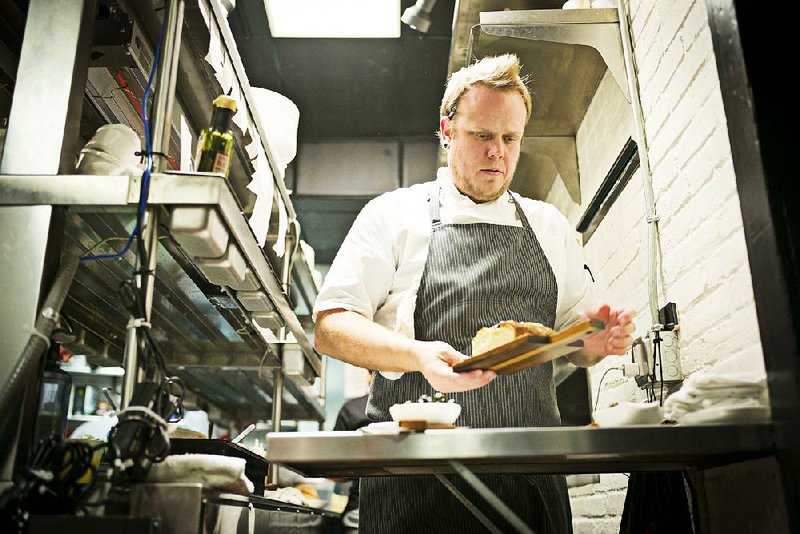

Those in charge of menu-writing have a fine line to walk. They want things to sound interesting, maybe a little exotic -- especially compared with what someone might cook at home -- but not pretentious or twee. "There's a certain degree of what I like to call 'look-at-me' menu-writing," said Haidar Karoum, the former executive chef at Washington's Doi Moi, Estadio and Proof, who just opened Chloe, his first solo restaurant.

That can be an issue, he said, because "you don't want people to feel stupid for asking a question."

Even well-versed chefs can find themselves unsure of what they're reading. Chef-partner Tony Chittum of Iron Gate Restaurant in Washington recalled eating a while back at Babbo -- the famed Italian restaurant in New York that is part of the empire Mario Batali, amid sexual harassment allegations, recently stepped away from -- and being thrown off by the extensive use of Italian words.

Chittum, by the way, is an expert in Italian cuisine.

It's perfectly reasonable for restaurants to use languages other than English. Thip Khao's menu, for example, explains that khaonom mun falang are yellow curry potato puffs, and Bibiana translates Polpette della Nonna as "chef's grandmother's meatballs." But what can be frustrating is a seemingly random string of words, presented without explanation.

Chefs can see the effects in terms of sales. "It's a little bit of trial and error" in settling on the right language, Karoum said. "You can tweak one word in a menu description, and you'll go from selling 10 [of a particular dish] in a night to selling 30."

Chittum saw firsthand the effect when he made a change. His menu featured an Italian dish called crespelle, made with stuffed crepes. Problem was, diners didn't know what that meant. So he swapped in the term cannelloni, which is technically made with pasta, but something more customers were familiar with -- and, just like that, the dish became more popular.

There are certain buzzwords or phrases that put people squarely in their comfort zone. Karoum cited the now-ubiquitous molten chocolate cake, which originated with New York chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten, as an example of how to nail a name. It's enticing and paints a picture in just a few words.

Karoum was going for something similar when he was brainstorming names for the flatbread that accompanies the spiced beef hummus at Chloe. The creation was a "labor of love," a combination of a dozen recipes, and when it came time to name it, he realized referring to it as "naan" just wasn't enough. Instead, he settled on "snowshoe naan," which comes from an Afghan recipe and conveys the shape of the bread.

"It sounded cooler than 'flatbread,' " Karoum said. A lot of diners will know what naan is, but Karoum said he hopes "snowshoe" will get diners to ask questions and learn more about it.

Chittum said he likes to throw in an Italian, Greek or technical term every once in a while to get customers and staff to interact. But he also admitted his menu composition is sometimes driven by other factors -- including his own whimsy.

One thing he considers is how the menu actually looks. Chittum will occasionally add or subtract a word to get a line to be longer or shorter, although he tends to err on the side of brevity. The Brussels sprouts salad at Iron Gate, for example, is described as having "two apples" on the menu, which at first glance seems to say, "Yes, you're eating a lot of fruit. Good for you!" In reality, Chittum said, the phrase indicates that there are two types of apple in the salad -- Granny Smith and Honeycrisp.

In other instances, it's all about how something sounds. "When I look at a dish, sometimes I feel like I need another descriptor," he said.

Hence, Iron Gate's "chef's deviled hen eggs."

You may wonder: As opposed to rooster eggs? When is an egg not from a hen? The redundant descriptor has a bit more of a special ring than "deviled eggs," Chittum said.

Sometimes, he confessed, it merely comes down to one goal: "You want to make things fancy."

High Profile on 02/11/2018