Adam Faucett is looking around the room where he does most of his songwriting.

"All my stuff is in bags," he says, scanning the lightly cluttered space in the Little Rock apartment he shares with his girlfriend, Katy Griffin.

Adam Faucett Record Release Show

9 p.m. Saturday, White Water Tavern, 2500 W. Seventh St., Little Rock

Admission: $10

(501) 375-8400

He points to his stereo, some musical equipment and a few crates of records. "The things I own that aren't in bags are right there."

It should come as no surprise that the hard-touring singer-songwriter is more comfortable on the move. The 36-year-old has spent most of his adult life as a working musician, first with the band Taught the Rabbits and later as a solo act and with his group, The Tall Grass. Working on this close-to-the-ground, do-it-yourself level means constant travel and gigs that he usually books himself.

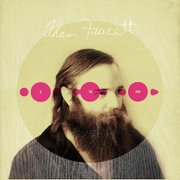

On this early evening in late May, Faucett is talking about his latest album, It Took the Shape of a Bird, a dark and riveting collection of songs that will be released Friday on Little Rock label Last Chance Records. A show celebrating the release is planned for Saturday at White Water Tavern in Little Rock.

The record is the follow-up to 2014's brilliant Blind Water Finds Blind Water.

"A lot of life happened in the past four years," says Faucett from behind his thick and mighty beard. "I've moved six times since the day I put out Blind Water."

...

It Took the Shape of a Bird is the sixth album he has recorded at Blue Chair Recording Studio in Austin (Ark.) with owner Darian Stribling. It's a relationship in which Faucett is clearly comfortable.

"I love going out there, and I love all the people I work with. When you've yelled at somebody so much, they become family," he says with a laugh. "I wouldn't say [Stribling] gets upset with me, but making a record's a real sensitive subject."

They started recording the new album more than two years ago, with Faucett and his longtime band The Tall Grass -- drummer Chad Conder and bassist Jonathan Dodson with help from touring drummer Jordan Trotter -- laying down tracks when everyone was in town and when Faucett could afford studio time.

Stribling, who engineered the record, says, "This is his best work yet. When people really give it a deep listen, I think they will enjoy this record more than any we've done."

Opening track "King Snake" starts with an uneasy tension. Faucett sings a dark tale from the point of view of an unwanted, orphaned girl in Camden. There's fear, the titular serpent, tears, angry men with drunken eyes. By the end, the song has broken its constraints and Faucett unleashes the girl's fury in a voice as clear and powerful as pure grain alcohol.

"So help me God/I'll kill him ..."

It's spine-tingling, Arkansas Gothic -- stomping, full-bore rock 'n' roll with fingerpicking folk roots, firmly situated in the natural world that tells a story of someone who has decided she won't be held down one second longer.

What follows are nine songs of dead ends and survival, breakups and weary souls that range from meditations like "Living on the Moon," "Dust" and "Sober and Stoned," to pin-you-to-the-wall tracks like "Pearl."

Many of Faucett's songs are based on real-life characters and experiences, with frequent name-checks of places like Camden, Benton and Sparkman.

"You build the world that is kinda halfway built for you and then you distort it a bit," he says. "I like singing through other people's perspectives."

It's a change from his own point of view.

"There are only so many songs you can write about being in a van and playing music."

...

Last Chance owner Travis Hill first heard Faucett during a solo acoustic set at White Water around the time of the 2011 album More Like a Temple.

"I was blown away by the power of his voice," he remembers. "He can command a room. Having the songs and the voice, he's undeniable."

Hill signed Faucett to the label and issued Blind Water Finds Blind Water.

"I'm pretty picky about who we throw in with, and I'm really happy to be working with him," he says. "Adam is a lifer and an extremely talented guy."

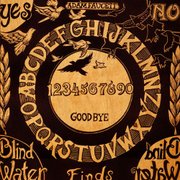

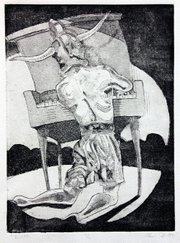

The cover for the new record, like the one for Blind Water Finds Blind Water and 2007's The Great Basking Shark, was created by Russellville artist Neal Harrington, who taught Faucett printmaking at Arkansas Tech University.

Faucett made an immediate impression.

"He was one of my first students when I got hired at Arkansas Tech in 2001," Harrington said. "He was a younger-looking version of what he is now. I thought, 'Who is this guy with the Nirvana shirt?' He's very quick-witted. He had talent in visual art, but I knew his direction was music."

Harrington had expressed interest in producing cover art for an album, should Faucett ever make one.

"A few years later, he says, 'Album's done. How about that artwork?'"

For It Took the Shape of a Bird, Faucett wanted nothing to do with avian imagery, instead coming up with an idea involving snakes, eggs and hands.

"First thing he says, 'No birds," Harrington laughs. "He brainstorms concepts and I execute them for him."

A short documentary about Harrington's woodcut art-making process at nealkharrington.com uses "King Snake."

"The song makes it. I'm a huge fan of his," Harrington says. "I've seen him develop over the years. Blind Water Finds Blind Water is one of my favorite albums. By the time he got to that, you knew he really had something there."

...

Faucett grew up primarily in Benton. His father, Dan, was a Xerox copier repairman and his mother, Jane, was a nurse at Benton High School. Both are retired now. He also has an older sister, Leah.

"What do you call a song," he counters, when asked when he started writing songs. "When I started writing songs that you would be able to listen to, I guess I was around 11 or 12."

In high school, he was "a lot like I am now, except dumber and high schooley, with all the hormones."

He and his friends spent their time "playing guitar and riding around smoking cigarettes, cutting up and trying our best to not have anything to do with school," he says.

He was devoted to '90s indie rock like Pavement, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr., Nirvana and Radiohead.

Faucett graduated from Benton High School in 2000, but he could have attended the Arkansas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. From behind orange-tinted glasses, his eyes dart continuously.

"I have ocular albinism," he says. "I'm legally blind in one eye, and I might be legally blind in both eyes. I don't really pay attention. I had a caseworker from the School for the Blind for my first 18 years."

He wanted to remain in public school, though, "because I didn't feel like I would ever learn how to get into a proper fist fight" at the School for the Blind.

Did he learn?

"Oh, God bless, yes," he laughs. "I found out the hard way."

Faucett also didn't let problems with his eyesight curb his pursuit of visual art.

"His artwork is pretty phenomenal," Harrington says. "It's interesting to work with someone like that, but he never complained about it. He was more dedicated than you'd think he would be."

...

With the release of the new album imminent, there are economic and creative anxieties.

"It's terrifying in the sense that you watch the bank bottom line go 'whoosh,'" he says. "There's no money coming in, other than little shows. I need to get it out and get back to work. If something breaks on the van, I can't afford to fix it. It's not very romantic, but it's the truth."

From the artistic side, he needs a little space after the recording process before he can appreciate what he has created with his bandmates and Stribling.

"I get real depressed about it," he says. "It doesn't even sound like music to me, but then I step away for a few months. Once it's done and mastered, it's like, 'Hey, maybe we didn't knock it out of the park, but we really hit that one. All that worrying was for naught.'"

Hill says the label's goal is to raise Faucett's profile "beyond Arkansas hero to national recognition." A publicist has been hired and an appropriately haunting video for "King Snake" is in the can, he says.

"I get really frustrated that people don't know who he is, but that doesn't happen much in Arkansas," Harrington says. "He needs to be way bigger than he is. He's amazing."

Faucett will spend most of the next year on the road, and will return to Europe, where he has toured twice before. At this level, it's not a particularly glamorous life. There are plenty of nights spent sleeping in the van.

But there is freedom, too.

"I like being gone," the singer says. "It's easier on the mind. It makes your world so much smaller. You don't really have to answer to anybody; there's no pecking order, no social circle. You roll through town and people like it or they don't, and then you leave. Rinse and repeat. I like the whole aspect of living on the road and, of course, I love the music."

Stribling says the path Faucett is pursuing is the right one.

"He was meant to be an artist, to make music. He realized that early on. A lot of people give in and then lead a normal life, which never gels with them. Adam decided this was his thing, this is what he is going to do, and he's stubborn enough to stick with it."

Faucett sips tea and ponders a question about persevering.

"I got fired from every job I've had," he says. "Wendy's, Pizza Hut, stock boy at an art supply store. What else am I gonna do? It's not persevering. That's like asking 'How did you end up eating dinner?' Well, you gotta eat dinner. I just know, with this body and these circumstances, there is nothing I can do better for myself or for those around me, than making up songs and singing them."

Style on 06/24/2018