Alex Martin was relieved to find Eugenia Jones and Willie Savage in the 1920 Census records.

That meant they weren't murdered the previous year during the Elaine Massacre.

It appeared they had fled -- Jones, 20, to Lake Charles, La., and Savage, 16, to Tunica, Miss., according to the 1920 Census. Both were living with uncles.

Martin couldn't be positive these were the same people who were living in Elaine in 1910, but he hoped they were.

"Eugenia Jones and Willie Savage were really kind of emotionally important to me because maybe they survived," Martin said. "Maybe they managed to get out and do something with their lives."

Martin was researching census records for an online class called "The Age of Reform" at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. The class focuses on American history from 1900 to World War II.

Martin, a junior from Boyce, La., is majoring in history and American sign language interpretation.

The Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history, according to an entry in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture written by Grif Stockley. It stemmed from tense race relations and growing concerns about labor unions.

"A shooting incident that occurred at a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union escalated into mob violence on the part of the white people in Elaine and surrounding areas," wrote Stockley. "Although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed by whites range into the hundreds; five white people lost their lives."

On the night of Sept. 30, 1919, about 100 black people, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of white landowners, attended a meeting of the union at a church in Hoop Spur, 3 miles north of Elaine. The purpose of the meeting was to get better payments for their cotton crops from white plantation owners, wrote Stockley.

Armed guards were stationed outside the church. A shootout took place in front of the church between the black guards and three people, resulting in the death of W.A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and the wounding of Charles Pratt, Phillips County's white deputy sheriff, wrote Stockley.

The next morning, the Phillips County sheriff sent a posse to arrest those involved in the shooting, but a mob of 500 to 1,000 armed white people had gotten word of the shootout by then and swept through the area, killing many black people.

On Oct. 1, 1919, Phillips County authorities requested that federal troops be sent to Elaine, but it appears they also took part in the massacre, wrote Stockley.

Stories differ on who fired the first shot, but hundreds of black people were arrested in the wake of the massacre.

With the 100th anniversary of the massacre coming up next year, Barclay Key, an associate professor of history at UALR, said he was looking for an Elaine project for his students in "The Age of Reform" class to work on.

The census records were revealing.

"A lot of people who lived in and around Elaine, black people, were missing from the 1920 Census," Key said. "It suggests a lot of possibilities. At the very least, they chose to get out if they could. It's haunting."

For most of the past century, the Elaine Massacre was a mystery to many people in Arkansas and across the country because there's a dearth of records about the tragedy, Key said.

But breaking the Elaine enigma requires research. It's a story not everyone wants remembered.

"The record was so distorted from the start," Key said. "There are varying claims about what happened. ... I've been out to Elaine five or six times, and there are still tensions over this incident."

Key's 13 students didn't have to travel to Elaine to do research for the class. It was all done online, with each student taking about 100 black Elaine residents from the 1910 Census and trying to find them in the 1920 Census.

"It was more depressing than I was expecting," Martin said. "We got this assignment to basically make a spreadsheet."

But the names that were missing from the spreadsheet on 1920 began to take on more meaning. Had parents died? Were children sent to live with more distant relatives in other states?

"It horrified me," Martin said. "The fact that something like that happened in my great-grandparents' lifetime is terrible."

Martin said it was difficult to track people with common names to other parts of the country. But Eugenia Jones and Willie Savage had somewhat unique names that made them easier to locate.

"Eugenia was more common then than it is now, but still uncommon enough that there were only a few Eugenia Joneses in the South, and narrowing that down by age and race made it even easier to find her," Martin said.

Martin said he found himself imagining what their lives must have been like.

"You want to find something good," Martin said. "You want to find out somebody went on and had a happy life."

The work Key's class did dovetails with work done last semester by another UALR class.

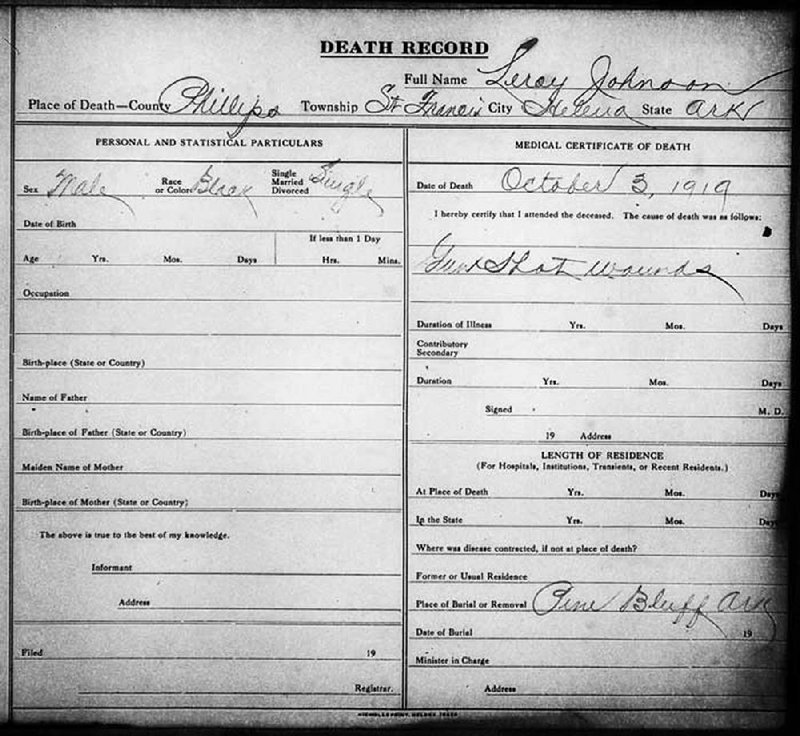

The 12 students in Brian Mitchell's "American Urban History" class created a digital index of Phillips County death certificates from 1917-22. A copy of the index has been donated to the Arkansas State Archives, an agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage.

The index allows people to search by name, date of death, primary cause of death, place of burial or other categories. It also allows viewing of images of the death certificates.

Melissa Whitfield, a spokesman for the Department of Arkansas Heritage, said there has been talk of posting the index online, but there are no plans to do so at this time.

Mitchell, an assistant professor of history, said the index his class created could be emailed to researchers, with hyperlinks included so they can see images of the death certificates. That could save researchers the expense of traveling to Little Rock to view the microfilm.

In 1990, the Tri-County Genealogical Society in Marvell allowed the State Archives, then known as the Arkansas History Commission, to microfilm the Phillips County death certificates from the Elaine Massacre era, Whitfield said. The originals remain in Marvell.

Mitchell discovered the death certificates at the State Archives last summer. His class indexed 665 death certificates for people who died in Phillips County from 1917-22. They include death certificates for 344 black people.

Mitchell said the index is the only "cohesive" record of black people's deaths during that period in Phillips County. He said the newspaper in Helena published few obituaries for black residents during that time.

Mitchell said he hopes the digital records will help identify some of the victims of the Elaine Massacre. But discovering the truth could be difficult. In some of them, the cause of death was listed as "gunshot wounds."

But in others, such as the death certificate for Calvin Miller, a 32-year-old black laborer who died on Oct. 4, 1919, the cause of death was simply listed as "hemorrhage."

"We know he bled to death during a riot, so we know he was killed there," Mitchell aid.

Other death certificates were purposefully vague on the cause of death or listed none, Mitchell said.

He said the massacre wasn't limited to the small town of Elaine. It resulted in deaths throughout Phillips County. And some death certificates weren't drafted until family showed up asking questions, which could have been months or years later.

Mitchell said the death certificates can also help black people who are doing genealogical research. He said there has never been a grave identified as being for a victim of the Elaine Massacre.

Guy Lancaster, who is editing a book of essays on Elaine and the larger historical context of the massacre, said the work done by the students in both UALR classes will provide a foundation for further research on the Elaine Massacre.

"And it's good practice for them to see what history really is," Lancaster said. "It's so easy to Google now."

On Tuesday, one of the students who worked on the Mitchell death certificate project was found dead in North Little Rock.

Damarian R. Williams, a 24-year-old man, died of "multiple gunshot wounds," according to the North Little Rock Police Department.

Mitchell said he was shocked.

Researching death certificates can be depressing, but Mitchell said Williams always looked for something funny to cheer up his classmates.

"He was always sort of an optimistic, funny kind of guy," Mitchell said. "And now he's gone."

Metro on 03/04/2018