Every tragedy is an opportunity, someone once said.

Otis Redding's "(Sittin' on the) Dock of the Bay" wouldn't feel the same had it not been released posthumously (it became the first posthumously released single to reach No. 1 on the charts). It wouldn't have sounded the same had Redding been around to finish it.

Redding died on a Sunday afternoon. On Monday morning Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler, who distributed Stax Records, called the Memphis-based label's co-founder Jim Stewart demanding a new single. Stewart turned to house producer and Redding collaborator Steve Cropper, who had a master on its way to Wexler in New York by Wednesday.

If Cropper had had more time, the Staple Singers would have backed Redding on the record. Maybe Redding's whistling would have been replaced with more lyrics. And surely Cropper wouldn't have put those cheesy seagull and crashing wave sounds on the record. He would have polished it a little. Maybe a lot. Maybe too much.

Maybe "Dock of the Bay" would have been just another song. Maybe it would have charted, maybe it would still come up in the golden oldies of the baby-boom rotation from time to time. It wouldn't be the wistful expression of unbearable regret it now presents as being -- it wouldn't be a call from beyond the grave.

And that would have been better. Because maybe we'd still have Redding around, and maybe he'd have had a fruitful second act.

But we can't have that. So we get "(Sittin' on the) Dock of the Bay" as recompense.

It hit No. 1 on Billboard 50 years ago this week.

. . .

It was 3:28 p.m. Dec. 10, 1967, when 26-year-old Redding's nearly new Beechcraft Model 18 went down in the cold waters of Lake Monona three miles from the runway at Truax Field in Madison, Wis. It was foggy, rainy and cold, and there was talk of flights being grounded. Redding's 26-year-old pilot Dick Fraser had flown just 118 hours in twin-engine aircraft and most of that was logged in a Cessna 310, much lighter and less powerful than the Beech 18.

The National Transportation Safety Board never reached a firm decision about the cause of the crash, attributing it to multiple factors, which is a polite way of saying that someone displayed bad judgment. General aviation is nearly as dangerous a mode of transportation as driving an automobile; its pilots are not as experienced, the airports it uses aren't as well maintained, the aircraft lack the safety equipment and redundant systems of larger commercial aircraft.

Yet the Beech 18 was not one of those planes that has acquired a grim nickname; while pilots sometimes called its smaller single-engine stablemate the Bonanza a "doctor killer," the Beech 18 was known, mostly affectionately, as the Bugsmasher. It was well-respected and Beechcraft manufactured it for 32 years, from 1937 until it was phased out in favor of the King Air, an upscale turboprop model. Holding up to 11 people (Redding's was modified to seat nine, with room for the band's gear), it saw action as a light bomber and cargo plane during World War II. The U.S. military used it until 1976. Some are still in use today.

Redding had bought the plane a few months before, in part to facilitate a more relaxed schedule that had him working at home in Macon, Ga., or Memphis during the week and flying off to do shows on the weekends. This arrangement worked well for his backing band, Memphis-based Bar-Kays, several of whom attended junior college. Bassist James Alexander had just begun his senior year of high school.

While the list price on a new Beech 18 was around $250,000, Redding's management was able to buy a used one from a Pennsylvania construction company that was planning on upgrading to the King Air. The price was $78,000, and they were willing to finance it. So Otis Redding Enterprises put $28,000 down and painted the company's name in script high on both sides of the fuselage.

Contrary to urban legend, the Beech 18 Redding bought was not previously owned by James Brown, although Brown had owned a similar plane which he apparently had not enjoyed. Whether he actually warned Redding not to buy the plane is a matter of conjecture, though Brown probably claimed as much. In his autobiography, Brown says Redding was fooled into buying a plane that was unfit for the purposes he put it to:

"They tried to do the same thing with his twin-engine that I did with a Lear jet and they could't do it," Brown wrote in James Brown: The Godfather of Soul (Da Capo, 2003). "That plane was an old plane with a bad battery and a lot of service problems and it had no business flying in that kind of weather."

Redding and the Bar-Kays were scheduled to play two shows at a Madison club called the Factory that night, the first at 6:30 and a later one at 9. The opening act was a local band called the Grim Reapers, which featured future Cheap Trick guitarist Rick Neilsen. Tickets were $3 in advance, $3.50 at the door.

William Barr, a 20-year-old sophomore at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, drew the poster for the event, which featured a woman seemingly covered by foliage, that he later said was inspired by Redding's 1966 hit "Try a Little Tenderness." Some people think it looks like the woman's head is protruding from a coffin. At her feet is a heart, reminiscent of Catholic sacred-heart imagery, through which vines have grown.

The Reapers had played their set when club owner Ken Adamany, who also managed the band, came on stage and told the crowd that Redding's plane had crashed. So everybody went home.

. . .

The impact with the water split the plane open like a tube of biscuit dough, filling the fuselage with water. Ben Cauley, the Bar-Kays' 20-year-old trumpet player and singer, was the only one of eight people on board to survive the crash. He was sitting directly behind Redding, back to back with the singer, who was buckled into the co-pilot seat.

Four other Bar-Kays -- guitarist Jimmy King, organist Ronnie Caldwell, drummer Carl Cunningham and saxophonist Phalon Jones, all teen-agers from South Memphis -- also perished. So did Matthew Kelly, a 17-year-old valet who roadied for the band and hoped to become a full member. (Redding himself was a valet; he drove for guitarist Johnny Jenkins when he first arrived at Stax in 1962, a trip that led to his recording "These Arms of Mine," which became his first hit.)

There wasn't room on the plane for Alexander and Bar-Kays' vocalist Carl Sims; they'd flown commercial from the band's prior gig in Cleveland to Milwaukee. They expected Fraser to fly up and ferry them to Madison after he dropped the others off. Instead police met them at the airport and drove them to Madison where Alexander ended up identifying the bodies.

Within a month of the crash, Cauley and Alexander re-formed the Bar-Kays -- adding saxophonist Harvey Henderson, guitarist Michael Toles, organist Ronnie Gorden, drummer Willie Hall, and later lead vocalist Larry Dodson -- and went on tour.

. . .

By most accounts, "(Sitting on the) Dock of the Bay" was written and recorded just a few days before the plane crash.

But the roots of the song go back to the Monterey Pop Festival in June where Redding, backed by Booker T. & the M.G.s (which included Cropper on guitar and Duck Dunn on bass), had gone over well with the largely white crowd. Redding, arguably the biggest soul singer in the world at the time, was anxious to cross over to mainstream pop success, to rival the Beatles and Glen Campbell. Stax executive Al Bell had cautioned Redding against being tagged as a genre artist and had suggested he explore more folk-like material, what Bell called "Soul Folk."

Redding was beginning to turn his attention more toward writing and producing; he'd had success producing Arthur Conley's hit "Sweet Soul Music" earlier that year. Over the years Cropper has often talked about how Redding wanted to start a new phase of his career, one focused less on touring and performing and more on writing and recording.

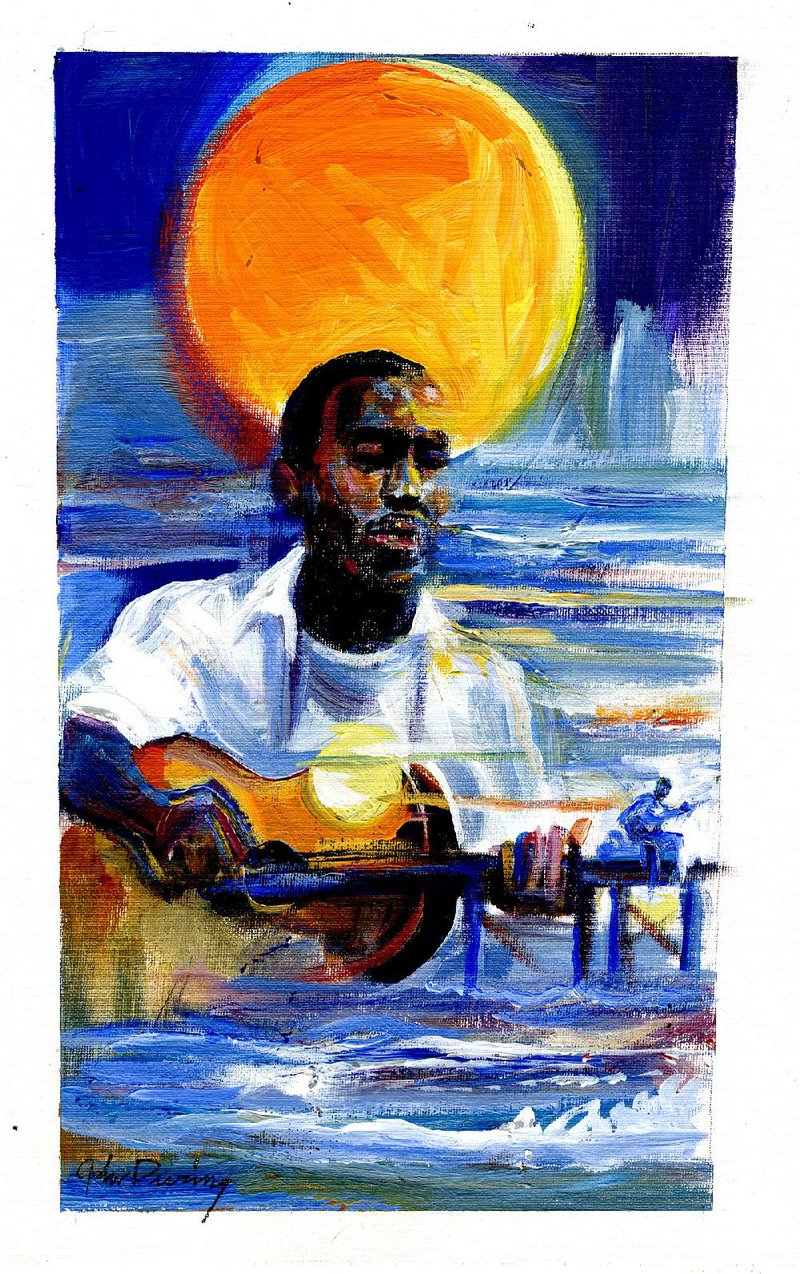

In August, he started a six-night stand in San Francisco, and promoter Bill Graham set him up with a houseboat at Waldo Point in Sausalito. It was here he first got the idea for the song -- Cropper remembers Redding having the first couple of lines, the bit about "watching the ships roll in" along with the basic chords.

That fall, Redding was diagnosed with polyps on his vocal cords; after surgery he was forbidden to sing or even speak for six weeks. He communicated through written notes. He moped around the house and annoyed his wife, Zelma. He wrote lyrics.

And when he could sing again in November he sounded great. He recorded more than 30 new songs at Stax's Memphis studios in November and December 1967; almost all of them (including "Hard to Handle," "I've Got Dreams to Remember," and "I'm a Changed Man") would end up on posthumous releases. Most of them feature Cropper's Telecaster a little more prominently -- while still recognizably soul, they were moving toward rock.

. . .

You can hear the first take of "Dock of the Bay" if you want to. It was released on a 1992 compilation album and is readily available on the internet. It's a simple four-track recording, with Cropper blocking out what sounds like barre chords on an acoustic guitar (probably an old Gibson B-25, although Cropper has sometimes identified it as a B-29, a non-existent model).

Redding starts out by making bird calls, which sound like crows but are apparently meant to be seagulls (and which inspired Cropper to later seek out the sound effects record). The rhythm section consists, as it usually did, of Dunn on bass and the inimitable Al Jackson, who plays a gently insistent 4/4 rhythm. Booker T. Jones played piano, and three horn players were enlisted to play on the track.

The vocal take starts out sure, though Redding botches some lyrics near the end (in the bridge he complains he can't do what "20 people" tell him to do; in the familiar version the scansion is improved by halving the number of busybodies). But what wrecks it -- or makes it, depending on your point of view -- is how Redding murders the whistling in the final verse. Recording engineer Ron Capone opens his mike to offer that Redding isn't "going to make it as a whistler."

Over the years, Cropper has sometimes suggested that the whistling was just a place-holder anyway; that Redding and he intended to write another verse for the song. But that never got done. (Other times he has maintained the whistling was seen as an integral part of the song from the beginning. He always dismissed rumors that a ghost whistler was brought in to do the part for Redding.)

Lyrically, Cropper takes over with the second verse, the one that begins, "I left my home in Georgia," an obvious allusion to Redding's Macon roots. Cropper (who can be heard talking about the track on his website at playitsteve.com/behind-the-songs) says that although Redding was reluctant to write about himself, Cropper was not. Still, Redding was at a high point of his life when he sat on Graham's houseboat, the line about not having anything to live for certainly isn't autobiographical. In 1967, Redding wasn't about wasting time.

It has sometimes been reported that Cropper got the idea for the bridge from the pop group The Association ("Cherish," "Windy") but these days he says he doesn't specifically remember the band as an influence but allows for its possibility. In any case, the tempo changes in the bridge, allowing for a little gathering of momentum and tension before releasing back into the verse.

Some people talk about the unusual chord structure of the song's verse -- the first bar of the song ("Sittin' in the morning sun") is G, moving to B (or B6, if you're fancy), to a C and a wonderful chromatic slide down to A (the guitar plays the chords C, B, B flat and A in quick succession) as Redding caresses the phrase "when the evening comes." While it makes no sense by traditional music theory standards when you consider that Redding (a big man, with huge hands) was a rudimentary guitar player who kept his instrument tuned to an open E chord, it's easy to see how he came up with the pattern.

He simply pressed down all the strings at the third fret (G), moved up the neck to the seventh fret (B), up one more to the eighth (C) then slid his hand back down to the fifth fret (A). It sounded good; who cares if all the chords are major?

Cropper doesn't play it exactly this way (that might be a B7 chord he's strumming) but the song really came to life on Dec. 8, the last day he saw Redding. That's when he brought out his Fender Esquire (now in the Smithsonian Institution) and, beginning with the second verse, began to decorate the song electrically, hammered on major thirds, arpeggios and the like, high up on the neck of the guitar. The idea, he says, was to capture the feeling of seagulls.

That was Friday. Redding died Sunday. Wexler demanded a fresh record Monday. Tuesday morning Cropper was back in the studio. There was no time to get the Staples in for their planned backup vocals. He went to a local jingle company and borrowed a loop of seagulls and ocean waves from their effects library.

Wednesday he took his master to the airport and handed it off to a flight attendant bound for New York. By Christmas 1967, there were promo copies in the hands of disc jockeys. The song was released on Jan, 8, 1968. It took it a few weeks to climb the charts, arriving at No. 1 on March 16, 1968.

It eventually sold more than 2 million copies. It eventually became one of those unavoidable cultural artifacts that exists beyond taste and time. Born of an almost ghoulish opportunism, it turned out to be as immortal as anything our kind is likely to make.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 03/11/2018