CROSSETT -- The release of hydrogen sulfide by a Georgia-Pacific paper mill here went unchecked and unregulated for decades, company officials said, and people who live nearby blame the toxic gas for their labored breathing.

Citing findings from two recent air monitoring programs, state health officials said the amount of hydrogen sulfide in the air in Crossett is routinely below thresholds that determine whether air is safe to breathe. However, the amount is frequently well above the levels at which the odor -- which can also cause health problems -- can be detected.

The monitoring findings come after the mill significantly reduced its emissions of the compound that is common to paper mills, an effort that began when a long-delayed federal rule first compelled Georgia-Pacific to disclose how much hydrogen sulfide it was releasing, public records show.

Sometimes abbreviated as H2S, hydrogen sulfide can cause eye, nose and throat irritation, headaches, poor memory and balance problems, as well as breathing difficulties for people who have asthma.

For years residents have expressed concern that the air was harmful to their health and property.

Sylvia Howard, 58, said the foul-smelling gas often aggravates respiratory problems for her, her children and her grandchildren. They live on the east side of Crossett, southeast of the paper mill and east of its wastewater treatment plant, where most of the emissions occur.

"If they paid me, I'd get out of here tomorrow," Howard said in reference to buyouts some Crossett homeowners received years ago from Georgia-Pacific after allegations that dirty air from the mill had damaged their property.

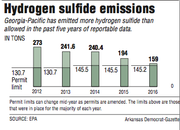

Hydrogen sulfide -- which primarily rises as steam from dirty water drained from the facility -- far exceeded the mill's state air permit limit every year from 2012-16, according to the company's self-reported figures. Yet, Georgia-Pacific has not faced penalties related to its release of the gas.

When informed by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that the mill exceeded its permit limit in 2016, the latest year for which data are available, Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality officials said they did not know the company had done so. The agency later refused to answer specific questions about air monitoring and emissions exceedances at the facility.

The emissions summary table in the permit lists "total allowable emissions," including "total reduced sulfur," which includes hydrogen sulfide. But the summary table is not an enforceable part of the permit, according to department officials.

Only limits listed in the permit for specific emissions sources are enforceable, department officials said. The wastewater treatment plant is not listed as an emissions source for total reduced sulfur.

Georgia-Pacific officials said hydrogen sulfide emissions from its wastewater stream were not factored into its state air permit limit and thus weren't restricted because the company did not know how to properly measure how much of the gas it was releasing.

Traylor Champion, Georgia-Pacific's senior vice president for environmental affairs, said it is more difficult to measure emissions from a water source, such as the wastewater treatment system, than a stationary source, such as a boiler.

"Until you're confident in what the emission rates are for a process there or even know how to calculate those, those are generally not accounted for in permits," Champion said. "Now that we have got a good way to account for these, we've been acknowledging those emissions since back in 2012 in the state [reporting database]."

Georgia-Pacific began working to reduce emissions at the mill after the EPA lifted an administrative stay on a rule requiring companies to publicly report hydrogen sulfide releases. The rule had been delayed for 13 years, in part by industry protest.

The emissions summary table in the permit lists a limit for "total reduced sulfur," which includes hydrogen sulfide and three other compounds.

The mill has reduced its emissions 42 percent since 2012, from 273 tons in 2012 to 159 tons in 2016, the latest year for which data are available.

The mill's permit in 2016 listed the total reduced sulfur limit as 145.2 tons in the allowable releases table. The limit changed a handful of times during the period but didn't top 145.5 tons.

The facility's draft updated air permit, under review by the Department of Environmental Quality, specifically includes hydrogen sulfide emissions from its wastewater stream. The total allowable release table in the draft permit lists a total reduced sulfur limit of 378.7 tons.

Wilma Subra, a scientist hired by the Louisiana Environmental Action Network to study the air in Crossett, said she believes residents have experienced the health effects of hydrogen sulfide. The network has filed complaints about the mill with the EPA.

"It was surprising they hadn't regulated hydrogen sulfide until this permit," Subra said. "You only know if it's too much if it's included in their permit."

No public data exist to show how much hydrogen sulfide the mill released before 2012. Air monitoring there did not begin until October 2014.

How much the company knew about the volume of its hydrogen sulfide emissions before publicly disclosing it is unclear. Jennifer King, public affairs officer at the company's Crossett facilities, said Georgia-Pacific did not estimate emissions systematically across the entire wastewater treatment system until recent years.

Georgia-Pacific has long grappled with air-quality issues. In the 1990s, it paid more than 100 settlements to Crossett residents to cover claims for corroded air-conditioning units, swing sets, basketball goals and other property, Champion said. An independent arbitrator heard the claims, and Georgia-Pacific paid damages based on those findings, he said.

Around that time, Georgia-Pacific tried to reduce the hydrogen sulfide odor in the Crossett community by routing wastewater through closed pipes rather than letting it flow openly, Champion said. The move did not reduce emissions but moved them farther downstream from the mill and some homes.

Since it began disclosing its hydrogen sulfide emissions, Georgia-Pacific has been one of the nation's leading producers of the compound. In 2016, it was 13th of 508 facilities in hydrogen sulfide emissions.

The Department of Environmental Quality has not issued any enforcement actions related to hydrogen sulfide for Georgia-Pacific's pulp and paper mill in Crossett. It has issued three consent administrative orders against the paper mill since 2016, which was the first in several years, related to excess carbon monoxide and oxygen emissions.

The EPA's enforcement has centered on other issues -- too much chlorine and chlorine dioxide on-site, violations of hazardous waste laws and failure to monitor certain chemicals discharged on-site -- at the Crossett facilities.

ASH BASINS TRIAL

Hydrogen sulfide is released into the air following a process of mixing substances that contain both hydrogen and sulfur at high temperatures to break down wood for making paper.

The wastewater treatment plant handles the hydrogen sulfide-laden byproduct of the paper-making process, which generates 43 million gallons of wastewater per day, King said.

Georgia-Pacific funnels its wastewater southwest of the mill and the town's center, and the water flows into the Ouachita River miles away after it is treated with chemicals and filtered of solids.

The wastewater path -- the focal point of the EPA's hydrogen sulfide monitoring -- runs near some homes. It is there, at places like Thurman and Penn roads in west Crossett, where hydrogen sulfide is most prevalent and the odor most pungent.

Mill officials and air-monitoring results have identified a pair of ash basins along the water treatment path as a major source of hydrogen sulfide. Last year, the mill received approval from state environmental regulators for a trial to send its wastewater past the basins to further lessen the emissions.

Bypassing the basins would not limit the mill's "ability to comply with ... permit limits," the company wrote, because the solids would be removed downstream at other basins.

In December, the company told the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality that there have been "no significant changes observed" in the amount of solid material discharged downstream since the trial began.

The change was the latest regulators approved on a temporary basis dating to 2014 that Georgia-Pacific proposed to lessen emissions. The company previously received approval to pump more oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and iron salts into the system, according to permit records.

MONITORING

A report released last month by the EPA doesn't show hydrogen sulfide at levels in the community that would cause concern, public health officials said, but it indicates consistent measurements of the "rotten egg" smelling substance in most locations that are well above the level at which people begin to smell it.

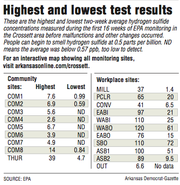

The EPA's monitoring took place over 24 weeks from January through June 2017. The agency placed nine monitors in the community and another 11 on Georgia-Pacific property. Malfunctions and changes in operations rendered the last eight weeks of data incomparable with the previous 16 weeks of data, the report said.

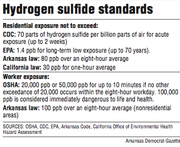

Various thresholds, including state law, set different standards for how much hydrogen sulfide in the air is too much.

All wastewater systems are exempt from Arkansas Code Ann. 8-3-103. The law, passed in 1999, stipulates that no facility is allowed to emit hydrogen sulfide to the extent that it would cause concentrations of the compound above 80 parts of hydrogen sulfide per billion parts of air in a residential area, or 100 parts per billion in a nonresidential area in an eight-hour period.

Arkansas Code Ann. 8-4-103 requires the Department of Environmental Quality to create standards and regulatory controls for hydrogen sulfide to "protect public health and the environment," but a search of department air regulations yields no results for "hydrogen sulfide."

Since 2014 -- when Georgia-Pacific, the Department of Environmental Quality and the Arkansas Department of Health installed a continuously running air monitor near the wastewater system and next to houses -- concentrations have exceeded 80 parts per billion in an eight-hour period three times. The last was Jan. 30, 2017, according to Health Department reports.

The EPA's monitoring last year -- which compiled averages over two-week periods -- recorded concentrations of hydrogen sulfide above 100 parts per billion four times at three sites on the mill's property. The highest community monitor reading was 39 parts per billion on Thurman Road near the wastewater treatment plant, but most community readings hovered around 2 parts per billion.

Before installing the monitors, the EPA used handheld monitors to detect hydrogen sulfide concentrations and measured concentrations as high as 5,680 parts per billion near the plant's wastewater treatment system southwest of town and 8,000 parts per billion at the mill in the city, according to the report. The report noted that frequent wind from the south blows air north of the plant, where the EPA recorded the highest concentrations.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry considers 70 parts per billion over a two-week period as its health screening threshold.

In the more than three years of monitoring, the Arkansas Health Department has issued 25 announcements noting exceedances of 70 parts per billion during 30-minute, eight-hour or 24-hour rolling averages.

In the reports, the department describes the air as possibly affecting "sensitive individuals, such as people with asthma and other chronic respiratory conditions," temporarily. The department has not issued any announcements since April 2017. The latest monitoring report goes through Feb. 6.

But Health Department officials note that while people may not experience long-term health effects from toxic hydrogen sulfide exposure, they can experience symptoms of exposure to the smell of hydrogen sulfide.

The CDC's Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry defines the level at which people can begin to smell hydrogen sulfide at 0.5 parts per billion. Some may not smell it until the levels are much higher.

According to the agency, the odor of compounds such as hydrogen sulfide or ammonia can cause dizziness, watery eyes, stuffy nose, throat irritation, coughing or wheezing, and sleep problems because of throat irritation and coughing.

Ashley Whitlow, epidemiology supervisor for the Department of Health, said the symptoms of smelling hydrogen sulfide are often similar to toxic exposure.

"What we're seeing hasn't really corresponded with anything that can be lasting, harmful effects of someone's health," Whitlow said, "but we are hearing from the community that they are still having symptoms."

The department, in partnership with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, is working on a health consultation for the community that would study the quality of the environment and potentially offer recommendations for improving it.

LOCAL CONCERNS

Residents have complained about breathing dirty air for years, and the town has drawn national attention from media outlets that included CBS News, Newsweek and a documentary film called Company Town.

Crossett Concerned Citizens for Environmental Justice, headed by Rev. David Bouie, made an environmental justice complaint to the EPA about the paper mill in November 2011. It was followed by site visits, conversations and reports back to the shrinking town of 5,500 people.

Consistent with the Center for Public Integrity's findings on EPA inaction on other environmental justice complaints nationwide, the agency has not made a formal finding of discrimination at the Crossett facilities.

The town is 42 percent black, with 22.8 percent of residents living below the poverty line, higher than the U.S. average of 12.7 percent, according to the U.S. Census. Most of the 12 facilities that had higher hydrogen sulfide emissions were in small, poor communities that had higher percentages of minority-group residents, according to an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette review of emissions and U.S. Census data.

Andrew Hollins, 71, lives on North Missouri Street, just south of the mill and northwest of the wastewater plant. He said the dirty air aggravates his asthma anytime he can smell the paper mill.

Cassandra Green said the air causes her 8-year-old daughter's eyes to water and her nose to run.

"It bothers me," said Green, who is Sylvia Howard's daughter. "I can't breathe."

Howard and others said it seems like most people they know have issues with the air quality. Some say their eyes burn, their throats itch or their chests clog up when they are in Crossett but not when they travel out of town.

"Everybody is sick here," Howard said. "Then they want to say we're doing all right? Come on."

Other residents, including neighbors of those who complained about the mill, aren't bothered by the company or the air quality.

Crossett Mayor Scott McCormick worked summer jobs at the mill while he was in college. His father worked in the shipping department. His grandfather, an electrician from Louisiana, helped build the paper mill in the 1960s, he said.

"I imagine there's probably some validity to some of the complaints, but most of them, I would just think that I would discount them, certain individuals that are involved in them," McCormick said. "I think [Georgia-Pacific] is going to do everything that they can to take care of any problems that might be out there, and do the best they can to try to satisfy some of those complaints.

"I think some of them, you won't ever satisfy."

Metro on 03/25/2018

*CORRECTION: Hydrogen sulfide emissions from Georgia-Pacific’s paper and pulp mill in Crossett exceeded the state’s air permit limit from 2012-16. A previous headline erroneously described what the permit regulated.