A state law that grants Arkansas' prison director the authority to make determinations of competency of death-row inmates ahead of their executions was declared unconstitutional by the Arkansas Supreme Court on Thursday.

The state has been unable to schedule executions anyway because it lacks some of the drugs required by another law.

Attorneys for two death-row inmates, Jack Greene and Bruce Earl Ward, had challenged the competency law last year in a successful effort to stave off their scheduled executions. After a circuit judge in Jefferson County dismissed both complaints, the Supreme Court agreed to stays of execution to allow the justices time to consider the prisoners' arguments against the law pertaining to the prison director.

Two 4-3 decisions handed down by the high court Thursday determined that the law violated the men's constitutional right to due process.

Both cases were sent by the justices back to the circuit court in Jefferson County for further proceedings on Ward's and Greene's competence claims.

The high court's decisions overturn its precedent in the 1994 case Singleton v. Endell, when the justices upheld the law.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Dan Kemp said, "Simply put, section 16-90-506(d)(1)(A) [of Arkansas' Annotated Code] is devoid of any procedure by which a death-row inmate has an opportunity to make an initial 'substantial threshold showing of insanity,'" as required by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The code section referred to in Kemp's opinion authorizes the director of the Department of Correction to make an initial determination of the competency of condemned prisoners. Under the law, if the director is convinced that "reasonable grounds" exist to believe that a death-row prisoner is incompetent because of mental illness, the director is supposed to arrange for further evaluations. That evaluation would be conducted by the Aging, Adult, and Behavioral Health Services Division of the Department of Human Services.

If the director determines no grounds exist, he can allow the execution to proceed as scheduled. The statute doesn't explain how the prison director is to determine whether a death-row inmate is competent.

Both Ward and Greene were represented by federal public defenders with Little Rock's Capital Habeas Unit. The public defenders argued that the state law denies condemned prisoners full due process.

Kemp and the court's majority agreed, finding the law violated both the U.S. and Arkansas constitutions' due-process protections. But the justices declined to address other claims that the law also violated the separation of powers in state government.

Justices Robin Wynne and Courtney Goodson joined Kemp's opinion. Justice Josephine Hart wrote in a separate concurring opinion that the law was also unconstitutional in how it was applied to the prisoners.

"We're pleased that the court held the statute to be unconstitutional," said John C. Williams of the Capital Habeas Unit.

Three justices -- Rhonda Wood, Karen Baker and Shawn Womack -- dissented in both cases.

Wood and Baker said the majority failed to find a good reason for overturning a precedent that was more than 20 years old.

The court's decision comes at a time when neither Ward nor Greene -- nor any of the 30 men on the state's death tow -- face an immediate threat of execution.

The Department of Correction lacks two of the three drugs required by state law to carry out executions. Prison officials have conceded that they have given up the search for new lethal-injection drugs until lawmakers make it easier for the state to keep the public from learning where it gets its drugs.

The last executions in Arkansas took place in April 2017. Eight were scheduled and four men were put to death; the schedule of executions became the focus of international attention.

A spokesman for Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, whose office had argued to uphold the law, said in a statement that Rutledge was "disappointed" and would be considering legal options.

A spokesman with the Department of Correction declined to comment.

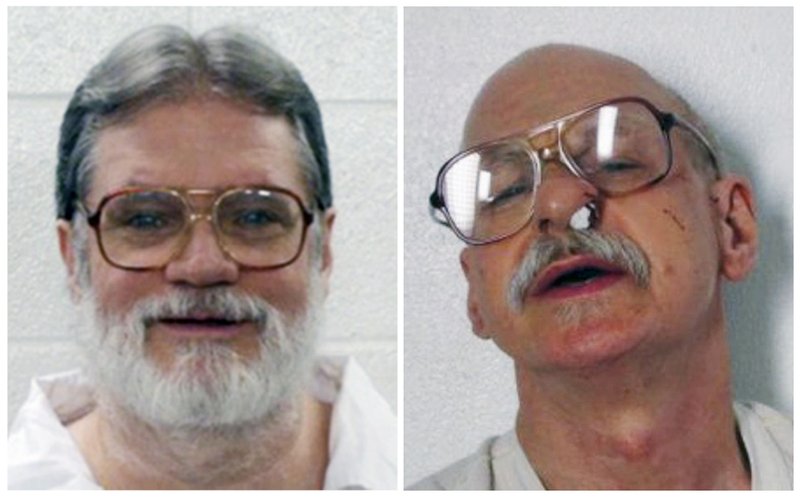

Ward and Greene are the oldest men on Arkansas' death row. Gov. Asa Hutchinson set Ward's execution to be among the eight scheduled in April 2017, before Ward and three others got reprieves. Hutchinson later sentenced Greene to die in November, before that execution also was called off.

Ward, 61, was sentenced to death for the 1989 strangling of Rebecca Doss in the restroom of the Little Rock convenience store where she worked.

While in prison, Ward was diagnosed with schizophrenia, his attorneys said in court records.

Greene, 63, has an IQ measured at 76, has been seen stuffing tissues in his ears and nose until he causes himself to bleed, and rants about his attorneys conspiring against him, according to his attorneys. He was sentenced to death for killing and beating Sidney Burnett in Johnson County.

At the time, Greene was on the run from North Carolina, where he was accused of killing his brother.

Both Greene and Ward have spent nearly all of the past two decades in solitary cells. They are housed at the Varner SuperMax prison.

A Section on 11/02/2018