Somber bells at 11 a.m. Sunday reminded Arkansans that a world war ended 100 years ago. We assembled in cemeteries to bow our heads for the grandfathers and great grandfathers, their sisters, their brothers, dead or missing, gone for service, gone for glory, gone forever.

But that's just us. We know what followed the War to End All Wars.

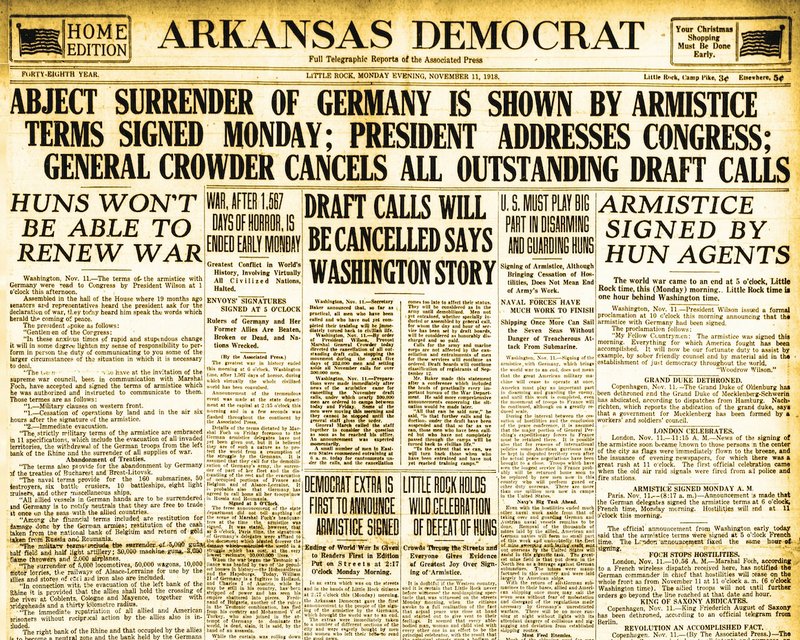

When news of the armistice broke 100 years ago, Arkansans didn't line up in the graveyard to pray for humanity. They blew stuff up.

As soon as word got around that it wasn't a fake-out, that Germany truly had agreed to call a halt to the Great War, Arkansans partied, hard.

George Wesley Morgan, white, aged about 38, was perhaps fatally injured yesterday afternoon at Markham street and Gaines, where he fell from the sidewalk over a fence and into a pit, landing on the pavement head foremost, a drop of about four feet.

The Nov. 12, 1918, Arkansas Gazette reported that Morgan, who had been celebrating, was hurried to the city hospital, where attendants thought he had a basal skull fracture. Witnesses said he had been walking east on Markham in a drunken condition.

The only "condition" legally allowed in Arkansas in 1918 was bone dry. Nevertheless, moisture was much on display during the 18 hours of explosive jubilation that reigned in Little Rock that long-ago Nov. 11.

Beginning "like a forest fire or a tidal wave through a broken seawall," the city was swept by what a Gazette reporter termed the wildest demonstration in its history. "Multiplied thousands of peace celebrants" waving flags, wearing the colors and operating every conceivable noise machine racketed through the streets.

Staid villagers whose customary bedtime was early had sat up far into the night to telephone the Gazette at regular intervals and inquire whether the armistice had been signed. About 2:15 a.m., the paper received a news flash and let fly the press.

Immediately upon distribution of the papers the big celebration began and lasted far up into last night. The streets were jammed shortly after dawn when the factory whistles of the surrounding country began blaring the news. ...

Hour after hour through the streets of Little Rock yesterday, pandemonium reigned. There is no past experience to compare it with. It had all the joy of all the Christmases that have ever been and patriotism of all the Fourths of July, the color and noise of 47,000 circus days and the confetti-covered camaraderie of a million street carnivals, the whole lot jumbled up into one tremendous occasion.

Several enthusiastic Puerto Ricans accosted a flag peddler and stole his flags. Hundreds of these "Porto Ricans," as newspapers spelled them, had been imported to work at the picric acid plant east of town. They raced down the street with the flags, whooping.

Several hundred Puerto Ricans paraded with flags, shouting with glee, like the Americans.

"Tanks" and "tanks" and more "tanks" wandered the streets, many of them digging into their family trunk for the old bottle which they had patiently saved up for this celebration.

From noon until 5 o'clock police rounded up 10 of these "tanks" (three guesses what tanks meant), taking only those who were unable to navigate any farther. With their horns, cowbells or whistles, they were locked up at headquarters until they sobered enough to be allowed out. That made headquarters a noisy place.

One tank walked right into a patrol car at Sixth and Center streets while it was returning from rounding up brawlers at 505 Main St. The driver saw him coming in time to stop and so instead of dying, he bounced off the door. Patrolman Rollins opened it and shoved him inside.

One man was caught twice for fighting, the second time at 505 Main, where somebody had called him a rat. He paid his bond and walked cheerfully out of headquarters, saying he was having the time of his life.

It was a hard day — a brutally hard day‚ for tin cans. When the possibilities of a string of tin cans dragged over the hard pavements by speeding automobiles became known, the city's "trash man" found his problems solved. Apparently all the garbage cans in the municipality were robbed of all bean, corn and tomato containers which had been discarded.

Thrifty sidewalk merchants sprang up like mushrooms, and a rushing curb trade was carried on in toy balloons, flags, "fish horns," and confetti. Fish horns were wooden vuvuzela-type monotone noisemakers designed for volume rather than for melody.

Many prominent citizens discovered hitherto unsuspected talents as impresarios and band directors and each block resounded with the music of its own private band. One rather sketchy imitation of John Philip Sousa passed down the middle of the street yesterday morning with a music outfit consisting of two bass drums, seven cowbells, a paper horn and a tin whistle, and for all practical purposes his aggregation served as well as any which ever played under the "march king."

A coffin bearing the chalked message "The kaiser has gone to hell" was paraded around town for hours. Eventually the pallbearers deposited it in the middle of Capitol Avenue's intersection with Main Street. They saturated it with kerosene and gasoline and set it ablaze to the delight of a rowdy crowd.

Afterward, they scraped the ashes into a heap and made a sign for it: "The ashes of the kaiser, Satan's chief dictator."

Medical men, presumably from some hospital, marched up and down Main Street with a skeleton hoisted in the air bearing a placard with the following words: "Was the Kaiser."

C.P. Mains, white youth, received three lacerations to his face yesterday afternoon when a Ford roadster in which he was riding struck a tree at 15th and Spring streets.

Mains had been trying to avoid a wagon that in some manner had blocked his passage.

Among the common noisemakers were revelers' personal revolvers, and as was traditional, these were pointed overhead and fired into the air.

At Fordyce, 35-year-old Will McDowell, a black man who was walking to his job at the Fordyce Lumber Co., was hit in the mouth by a random bullet fired by celebrator Joe Epps. McDowell died.

Frank Dunn of Cushman accidentally shot himself in the arm in the middle the night when for some reason he reached under his pillow and pulled out his revolver instead of the flashlight he also kept there.

Columbus, Ohio, isn't Arkansas, but C.E. Harrod's accidental killing of his wife after leaning out the bedroom window to celebrate the armistice made the Gazette's front page. Harrod thought his revolver was empty when he wheeled back into the room.

In Pine Bluff, Cecil Copeland, 21, became stricken with remorse for having deserted from Camp Pike the month before. During that month he was hiding out, he showed up at his parents' house once a week, in uniform, pretending he was on compassionate leave to see his new wife. But he was caught, and jailed at Pine Bluff awaiting transfer to Camp.

When the celebration began, his jailer stepped outside, and Copeland escaped. He ran home, where he drank tincture of lobelia mixed with chloroform. His beloved Leslie, 17, did so, too, leaving a note to her mother that she couldn't live without Cecil. Attempts to revive the couple failed.

SHOOTING ANVILS

The Gazette also reported that across the state, trains loaded with draftees on their way to Camp Pike stopped, and their passengers poured off to join the nearest parade.

Twenty thousand people paraded at Fort Smith.

At Malvern, a cannon recently presented to the town by then U.S. Rep. Thaddeus H. Caraway was filled with powder for the first time. The discharge broke windows.

But that didn't stop the parade, two miles long, in which "an English subject" dragged an effigy of the kaiser through the streets.

At Morrilton the shooting of anvils with blasting powder caused the breaking of windows. All powder in the city was sold out early in the day, and the blasting powder was secured from Russellville. A flock of wild geese flying over the city became confused by the deafening reports and discharges of firearms, and many of the flock fell in the city.

Anvil firing is still a thing. It has its own page on Wikipedia — not that we should be impressed. Anything could have a Wikipedia page. But I looked up "anvil shoot" on Youtube.com, and yes, there it is, complete with competitive versions.

The process appears to use two anvils. One is placed upside down on the ground, while the other is stacked upright atop it, feet to feet. The cavity in the base of the upended anvil is filled with black powder, rigged with a fuse. If the cavity of the top anvil also is packed, some sort of sealant keeps the powder in place. Like peanut butter.

Today there are safer methods, but in 1918 you found a fool to light the fuse and run like the devil.

There was no such disorder at Camp Pike, where routine was interrupted only by the joyful shouts from the boys in khaki as autoloads of civilians invaded the camp with their flags, horns and cowbells.

Little Rock Mayor Charles Taylor was so impressed by his city's rejoicing he actually turned aside calls for a more reverent observance on Sunday, Nov. 17.

"I doubt," he said, "whether the people of any community in the United States celebrated the victory with greater unanimity than did our own city."

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

Style on 11/12/2018