CHOCTAW -- It's a little before 11 on a crisp Wednesday morning and there's already a line outside the Choctaw Food Pantry.

Classic rock plays inside the metal building, which sits across the parking lot from the Church of Christ on Arkansas 330, as volunteers neatly organize cans of vegetables, gallon jugs of milk, fruit, cereal, potatoes, packages of frozen meats and other items.

Claude Ruiz, the soft-spoken pantry founder and director, gathers the volunteers into a circle where they hold hands and pray.

"Father we thank you for each day. We thank you for the blessings of life. We thank you for the families that you provide us. We thank you for the loving hearts of those who spend their time helping those who are in need ..."

The prayer ends and it's 11 o'clock, time for the pantry to open. The people who have been in line enter the pantry, some pushing little yellow grocery carts.

They check in with volunteer Floye Brewer, who takes their name and the number of people in their household. They then select their allotted amount of food from a table manned by other volunteers. It's like a buffet, but with groceries.

"I really do love it," says volunteer Diane Jackson, who is here on her day off from her job at a convenience store called Casey's just up the road on U.S. 65. "I tell my

employer that I'm going to my real job."

A steady stream of clients from all over Van Buren County will come through the pantry from its 11 a.m. opening until it closes at 6 p.m., just as they do every Wednesday.

"We serve about 400 families a week, somewhere between 1,200 and 1,400 people," says the 75-year-old Ruiz, who started the nonprofit food pantry 14 years ago. "We gave away over half a million pounds of food here last year. Van Buren County is a big area, and there are a lot of poor people here. Every week we have 11-25 new families sign up."

They are not alone.

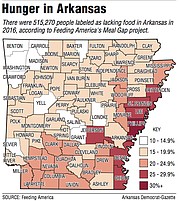

Arkansas ranks 44th overall in poverty, according to talkpoverty.org, a project of the advocacy group Center for American Progress. More than 18 percent of Arkansas residents experience hunger according to 2018 figures from Feeding America, a nationwide network of 200 food banks. One in four children are at risk for hunger in the state, as are one in five senior citizens.

The United States Department of Agriculture refers to hunger as "food insecurity" -- a lack of access, at times, to enough food for a healthy life for all household members and limited availability of nutritious foods.

. . .

"Hunger in America is real, but it looks very different. It's often right next to you and you don't realize it," says Rhonda Sanders, chief executive officer of Arkansas Food Bank in Little Rock. "Quite often it is someone on your block or at your church or in your Bunco group that has hit a hard time."

Arkansas Food Bank is one of six across the state that distribute food to local pantries, soup kitchens and charities. The others are Northwest Arkansas Food Bank at Springdale, Food Bank of North Central Arkansas at Norfork, Food Bank of Northeast Arkansas at Jonesboro, River Valley Regional Food Bank at Fort Smith and Harvest Regional Food Bank at Texarkana.

Of the six, Arkansas Food Bank is the largest, serving 280,000 clients in 33 counties in central Arkansas as well as parts of the eastern and southern areas of the state. About 320 local charities and food pantries, such as the one at Choctaw, work with the food bank to distribute food to those who need it.

"We are working with our agencies to help provide nutrition education concerning cooking on a budget," Sanders says. "We also help link clients with ways to learn about financial management."

Not all local charities use the food banks.

"There are those that don't want to be affiliated with anyone," Sanders says. "They want to do things the way they want to, and that's fine."

Arkansas Food Bank headquarters is the 6-year-old, 73,000-square-foot Donald W. Reynolds Distribution Center that also includes its well-stocked, 56,000-square-foot warehouse. Its yearly operating budget is about $7.6 million, mostly from donations, with about 10 percent to 12 percent from a government source, Sanders says.

There are 62 employees at the food bank, and by the end of the year, about 28 million pounds of food will have passed through the warehouse on its way to local pantries.

Macaroni and cheese, soups, peanut butter, rice, canned tuna and chicken are all pretty popular, Sanders says.

An initiative has been started to get more fresh produce, says food bank communications director Tyler Lindsey.

"We've had about 4 million pounds a year of fresh produce and vegetables. We'd like to increase that. I know this year we're going to be close to 5 million."

About 12,000 volunteers help at the food bank throughout the year, boxing items and handling other chores, Sanders says.

As for monetary donations, each dollar donated can be turned into five meals.

"We can leverage that dollar and turn it into lots of food," Sanders says.

. . .

Where does that food come from?

Just under 80 percent is donated by grocers, bakeries, dairies, farmers and government agencies, Sanders says; 15 percent is from federal commodities and 8 percent is bought.

Next year, as a result of the Trump administration's trade tariffs, the food bank expects to see a large increase in food it gets from the government as farmers and producers will have excess yields that would have normally gone elsewhere.

Local agencies order what they need from the food bank online. About 70 percent of the food is free, the other 30 percent has a handling fee of 18 cents a pound, or is bought at close to wholesale.

Annette Dove is the founder and executive director of the nonprofit Targeting Our People's Priorities with Service, Inc., (TOPPS), in Pine Bluff, which is an agency of Arkansas Food Bank.

Along with tutoring, mentoring and job training programs, TOPPS offers services for those who don't have enough to eat, providing meals for schoolchildren and food boxes for families and senior citizens.

"It helps us in a lot of ways," she says of working with the food bank. "We do emergency food boxes and then we also feed children daily, so we can get some items for a very reasonable price and then some of it is donated by the food bank."

In Jefferson County, nearly 30 percent of the population doesn't get enough to eat.

"A lot of times, people don't realize the need," Dove says. "We see kids and we think they're OK, but I've seen kids go in the trash to get food. They're hungry, and people don't realize that."

Agencies like TOPPS and the Choctaw pantry also get donations or reduced-price goods from local businesses, charity groups and companies such as Tyson Foods and Walmart.

"We welcome them going to local vendors," Sanders says. "They have their own food drives and raise money and spend it wherever they want to."

. . .

The Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) is a federally funded food safety net to help those with low income get food through cards that work like debit cards at grocery stores. Qualification is based on annual income and number of people in the household.

"If someone is eligible for it we want to see them on it," Sanders says of SNAP. The food bank even has a staff member who helps clients sign up for SNAP.

The food banks and the pantries they supply are a sort of filler during a crisis, or if SNAP benefits aren't enough.

"We're not feeding them every day of the week," Sanders says. "Our statistics show that people go to a pantry about seven times a year. We are providing that stopgap that allows them to use their income on other things -- gas for the car, electricity, medicine."

At the Choctaw pantry, volunteer Betty McCauley of Bee Branch can relate.

She and her husband were left homeless after a house fire March 30. They stayed in a hotel and got help from the Red Cross until they were able to buy a used fifth wheel travel trailer to live in. They also used the food pantry, where Betty volunteered even before the fire.

"I never thought we would need a place like this," she says as she takes frozen foot-long hot dogs from their shipping packaging and puts them into smaller bags for clients. "We had everything before the fire. We just didn't have insurance. Now I'm here to pay back just a little bit of what they have given to me."

In Pine Bluff, Dove says SNAP cutbacks have left some people with no other choice but to turn to TOPPS for help.

"I have grandparents coming here and they're only getting $30 a month, and that's not very much even for one person."

. . .

In 2004, the six food banks formed the Arkansas Hunger Relief Alliance, which handles, among other things, advocacy and education for those who go hungry.

"SNAP is covered in the 2018 Farm Bill," says alliance communications director Nancy Conley. "If they cut the budget as some members of Congress want to, that will be really serious for people in Arkansas. We have almost 400,000 people receiving SNAP benefits, most of whom are senior [citizens], children, disabled, people who can't easily go to work."

The alliance was pleased by the recent approval by Arkansas voters of Issue 5, which will raise the minimum wage to $11 an hour by 2021.

"Many who are low-wage workers make too much to qualify for SNAP, but they don't make enough to support their families with nutritious food, or enough food that will last from paycheck to paycheck," Conley says. "We were really happy to see [Issue 5] get approved. When people have more money to spend, they will buy more food. That will take some of the pressure off our food pantries."

The alliance also partners with farmers across the state to harvest excess produce as part of the Arkansas Gleaning Project.

"We take volunteers, and in some cases inmates from the Department of Correction, and go into the fields to harvest," Conley says. The bounty is then distributed to the food banks.

Educational programs such as Cooking Matters, where people learn how to shop and cook on a budget, are also a big part of what the alliance does, Conley says.

. . .

Speaking of education:

The Rice Depot, which merged with Arkansas Food Bank in 2016, started a backpack program that continues with the food bank. Easy to access, pop-top-type food is slipped into the backpacks of children who likely aren't getting enough to eat at home over the weekend.

"We serve about 3,000 kids a year that way," Sanders says. Many of the agencies the food bank helps, including TOPPS and the Choctaw pantry, have programs to feed schoolchildren.

And then there are the food pantries on college campuses.

"We have 10 college pantries in our area," Sanders says.

University of Arkansas, Pulaski Technical College in North Little Rock was the food bank's flagship college pantry.

"We started in August 2013," says Michelle Anderson, associate dean of students at Pulaski Tech. "We had students telling us they were hungry, or their families were hungry. There was often an emergency situation, and they had to put their money toward fixing a car or paying a medical bill instead of paying for food."

At first, impromptu donations would be taken up, but officials realized there was a greater need.

"There were students who were struggling," Anderson says. "They were going to school to try and better themselves, but they were hungry. I was aware there was a need, but not to the extent we've seen."

Student ambassadors volunteer at the pantry, which is funded by donations and is open on campus on the first Thursday of the month and by appointment over the summer. This month it was open twice, its regular time and then on a second Thursday to give away Thanksgiving-theme bags of food.

"We usually serve about 50 student households," Anderson says.

As with any other agency it serves, the food bank gives regular training and inspections to the college pantries and volunteers. There are also regulations like not requiring recipients to pray or attend church services to receive food and there is training in grant writing.

"They were our first call when we thought of starting a pantry," Anderson says of the food bank. "The fact that they can get food from Walmart and Kroger and produce from farmers and distribute it to us to give out is a huge help."

. . .

It's after noon now at Choctaw and the parking lot at the pantry is filling up.

Claude Ruiz's wife, Karin, who runs the pantry with him, is not here today. She's in the hospital in Little Rock. Ruiz was with her until it was time to make the hour-plus drive to get back here by 6:30 a.m. and get the pantry ready for the day.

"It's not easy," he says. "There's so much to it. So much to all of it."

Some of the clients are here every week, others not as often, Ruiz says.

"They're underprivileged. They can't get a job that pays enough to live on. And some of them are drug users, but they still have kids and the kids have to eat. There are a thousand stories here. A majority of them really appreciate it. A number of them think we owe it to them. We do it for the ones who are in need, and we get those here who are really needy."

Christina Newcomb is a homemaker from Bee Branch. She's waiting in line outside the pantry.

"It holds us over," she says of the groceries she gets here. "My husband's disabled, so until he gets his check, it helps us a lot. I don't know what we'd do without them here."

For more information about local food agencies, volunteering or to donate, contact arkansasfoodbank.org; arhungeralliance.org.

Style on 11/18/2018