Luke was a year and a half old when a bite of peanut butter changed his life.

His mother, Dr. Angela Chandler, knew something was wrong when the toddler's lips began to swell and hives bloomed on his skin. Tests confirmed a peanut allergy, and the family discovered a new world of everyday hazards: birthday cake, Halloween, sleepovers, restaurants.

"I think there's a misconception that a food allergy is just going to make you a little bit sick," Chandler said. "It's scary, as a parent, to know that your child could just eat something and then die."

That fear was part of what pushed the family to enroll Luke, now 9, in a large-scale clinical trial at Arkansas Children's Research Institute and 65 other sites across 10 countries. With results recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the trial points toward what could become the first treatment for peanut allergy.

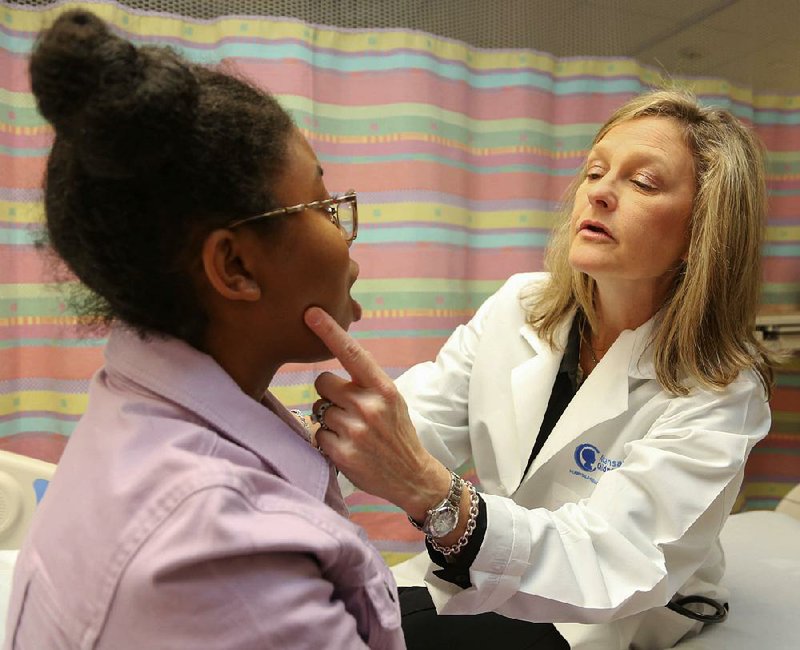

Dr. Stacie Jones, who ran the Arkansas research site and is an author of the manuscript, said the trial is the largest of its kind, and the therapy may change the rules for physicians and allergy patients.

"[This] provides some hope for us, as people that take care of children and adults, as well as parents and food-allergic patients," she said. "[Patients] can go to school more safely, or on field trips, or play in sports or go to college ... with more reassurances that their chance of having a serious allergic reaction is much less."

The trial studied a treatment in which participants received gradually increasing doses of a peanut protein "in hopes of downregulating, or densensitizing, the immune system," Jones said. It's considered an oral immunotherapy, which is a type of medication that works by activating or suppressing the immune system's response.

Of children who received the treatment -- all of whom had allergic reactions to just a third of a peanut -- 67 percent were able to tolerate the equivalent of about two peanuts by the end of the study, compared with 4 percent of those who had received a placebo. (The treatment wasn't shown to be effective in adults.)

Jones, who is chief of allergy and immunology at Arkansas Children's Hospital and a professor of pediatrics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, said trial sponsor Aimmune Therapeutics incorporated findings from several smaller peanut allergy studies, including a 2009 oral immunotherapy study she led at Arkansas Children's Research Institute with Duke University Medical Center. That report was the first of its type in the nation, according to a news release.

The recent trial is notable not just for its scope, which included almost 500 participants between the ages of 4 and 17, but for the fact that there haven't been any real treatments for food allergies beyond avoiding the food and access to epinephrine. "Very allergic" individuals had a "large treatment response" to this therapy, Jones said.

A fact sheet for Food Allergy Research & Education reports that as many as 15 million Americans have food allergies, and clinicians agree that they've been on the rise in recent decades. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention findings noted that food allergies among children grew by 50 percent between 1997 and 2011.

No one's sure why this is happening, said Dr. Drew Bird, director of the Food Allergy Center at Children's Health in Dallas and associate professor of pediatrics at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who is also an author on the New England Journal of Medicine article.

Theories include the "hygiene hypothesis," or a lack of exposure to germs and bacteria affecting the immune system's development; changing American diets; increasing use of the cesarean section as opposed to vaginal birth, which some think impacts the microbiome; genetics; and any number of other things.

"I don't know if we'll ever have an answer that says, like, aha, this is it," he said.

Though they're increasingly common, Bird said the impact of food allergies shouldn't be minimized because of the way they affect quality of life for individuals and families.

"Peanut[s], and foods in general, are just such a big part of our lives," he said. "This does place a significant burden on these families to avoid the allergen to keep their kids safe."

For patients with peanut allergies specifically -- there's not much overlap from food to food, Bird said -- the Aimmune Therapeutics treatment could make a big difference. If it wins FDA approval, it could be available by fall of 2019, a spokesman for the company said.

Jones stresses that this treatment isn't designed for patients to be able to eat peanuts, but rather, to protect against more severe or life-threatening reactions from accidental exposure and help ease anxiety for patients and their families.

"Many people with food allergy feel that much of the world is loaded with land mines for them," she said.

She also cautions that the treatment isn't something that can be safely replicated at home. The peanut protein is pharmaceutical-grade, meaning it's precisely measured and free of bacteria. Some people dropped out of the study because of side effects such as gastrointestinal problems, and researchers also worked at sites where there would be immediate access to medical care when patients experienced reactions, which Jones said was critical.

Nine-year-old Luke experienced uncomfortable allergic reactions to peanuts for the first time since he was small, Chandler said. But she said he wanted to move forward after seeing a friend do well on the treatment and because he knew it would help other children.

Earlier this spring, he passed his "food challenge," tolerating a small amount of peanut for the first time, she said. Although he has continued on the treatment and the family is still vigilant about ingredient lists, Chandler hopes continued therapy will lessen the chance of a reaction if he accidentally eats something he shouldn't.

Over the course of the trial, Luke also has learned what peanuts taste like, which is a safeguard she'd never known how to teach him. Now he knows, she said, and his verdict is in.

"He smells it, he tastes it and he does not like it," she said.

Metro on 11/22/2018