Top 10 lists can be fun, but they're of dubious utility.

Reading one can kind of be like looking at the titles in someone else's bookcase; you might begin to wonder if some of the books are displayed simply because they're putatively impressive. You might suspect that maybe the displayer hasn't really read all that Henry James. But while bookcases serve a real purpose -- they hold books, which even in our digital age have a genuine reason for existing beyond their symbolism -- all a Top 10 list really does is advertise the taste of the list-maker.

There's always an element of performance in putting one together; one needs to balance demonstrations of erudition with shows of down-to-earthiness -- you can put Andrei Tarkovsky's Mirror on your list but maybe you should throw in a popular middle-brow comedy like Animal House so people won't think you're a snob. It's OK to list a consensus all-timer like The Godfather or Citizen Kane so long as you also make a couple of idiosyncratic choices, like well, Charlie Kaufman's Synecdoche, New York or Louis C.K.'s Pootie Tang. Such lists always tell you a little about the person doing the listing, and that's fine as far as it goes.

Were I to list my Top 10 films of all time, it would simply be a snapshot of what I could remember in the moment. I have three or four or five movies that would be on the list most of the time, but's there's probably a hundred or more that might make it depending on my mood. If I were to earnestly strive to create something defensible, I doubt I would raise anyone's consciousness. The movies I default to are old and boring like The Third Man, The Searchers and Hiroshima Mon Amour. While (like most people) I don't carry a top 15 movie list around in my head, if I start to think about the subject I tend to come back to a few consensus choices. Sorry, no Dario Argento film is ever going to crack my Top 30.

But I'm working on a project that has sent me down a personal rabbit hole -- identifying the best films I've seen since the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks.

That date isn't entirely arbitrary; I'm working on a book project that uses the date as the bright line between "Before" and "After." I've borrowed the conceit from Arkansas-based filmmaker and composer Hans Stiritz's short film Before (2004), which I've written about a number of times and which you can find in several places, including here: tinyurl.com/y937fh8x.

While I'm finding making this list as slippery as any other -- Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away (2002) is on it; so is the Cohen Brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), the Dardenne brothers' L'Enfant (2006) and Todd Haynes' I'm Not There (2007), but I've got another 30 to 50 movies that slip on and off. (I'm accepting nominations too. What are the best movies released since Sept. 11, 2001?)

I saw a number of remarkable movies in the last hours of the 2001 Toronto International Film Festival, which was interrupted by the attacks. (It shut down for one day, then somberly resumed, closing on Sept. 15.) My notes indicate I saw Jez Butterworth's Birthday Girl, Antoine Fuqua's Training Day, Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Amelie, Richard Linklater's Waking Life, Alfonso Cuaron's Y tu Mama Tambien, Mira Nair's Monsoon Wedding and Danis Tanovic's No Man's Land. But unless you saw these movies at Toronto or another film festival, they belong to your After.

. . .

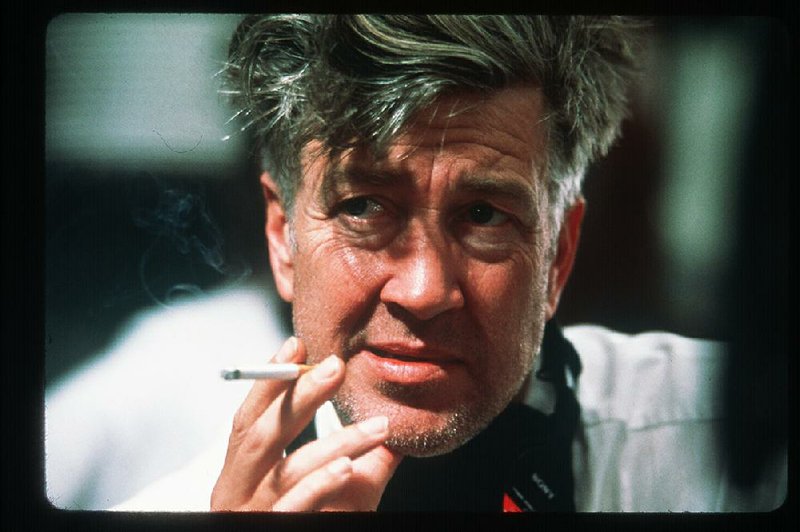

The more I think about it, the more I'm sure that the post-9/11 movie that most persistently engages my attention was David Lynch's Mulholland Drive, a movie that was actually cobbled together from footage shot for a failed TV pilot the pitched to ABC in 1999.

I say this despite my general skepticism about Lynch's work. I never was engaged by the original Twin Peaks (part of that had to do with my general indifference to television in those days) and I like The Elephant Man (1980) and Blue Velvet (1986) more than Dune (1984) or Eraserhead (1977). And while I allowed the 2017 Twin Peaks reboot to wash over me (maybe it was better because I didn't have strong feelings about the original), I thought it was more impressive as a piece of performance art than as cinema. (Though individual scenes and shots were devastating -- I could preach it either way.) My basic take is that Lynch is at his best when he's forced -- by commercial necessity or the desire to connect with a wider audience -- to murder his most precious darlings. Unalloyed Lynch is strong medicine, but so were a lot of the old patent medicines. They were still snake oil.

To that point, I still can't tell you what Mulholland Drive is "about"; I only know hardly a week goes by that I don't think about the film. Like the spiny route separating Los Angeles from the San Fernando Valley it's named for, Mulholland Drive twists and veers, careering through dim and woolly territories, an erotic noir that skids right up to the precipice of self-parody. It's Lynch playing chicken with his muse -- at times, it's almost difficult to believe that even he knows what he's doing.

There's a latent nastiness in its shadows, even when the screen is being splashed with SoCal sun and Pollyanna Ultrabrite smiles. Long and stately despite the violence and sex which comes hard and fast, Mulholland Drive is not the sort of movie most people think of when they think of Hollywood, even though it's the most Hollywood movie I know. What throws us is the atmospherics, the absence of the overtnessthat over the past 40 years has become the hallmark of American commercial cinema.

It differs from a puzzle film like Christopher Nolan's Memento (2000). Memento can be reverse-engineered, if you're patient, and part of the satisfaction derived from seeing it is feeling the code crack open in your head. (Like that moment when factoring quadratic equations finally began to make sense, if it ever did.) But Memento is just a well-made, tricky thriller, something that, if you wanted to seem like a cool appraiser, you could call a gimmicky movie.

Mulholland Drive on the other hand, is straight-up bizarre, a tone poem with loose ends and cracked dream logic. You have to be the sort of person who can tolerate ambivalence and willful weird wooliness to actually embrace Mulholland Drive. It feels like 147 minutes of inversions and improvisations.

. . .

Still, if you like that sort of jazz (and it is a kind of jazz), you'll be hooked from the moment a car comes screaming straight out of Rebel Without a Cause and into the limousine where a brunette (Laura Elena Harring) is about to be executed. Saved by the accident, she stumbles across the borders of Hollywood in an amnesiac's fog into an empty apartment to camp for the night. She's discovered the next day by blonde Betty (Naomi Watts), just arrived in Hollywood from small-town Canada. She's just won a jitterbug contest, and made friends with the elderly couple who judged it. (Or are they her proud parents or other relatives? And is Betty just a character in Diane's dream? Why do so many of the faces recur, was Lynch so cheap he had to re-purpose actors? )

Betty is naively confident she'll be a star and, in a scene worthy of Hitchcock, discovers the wild brunette showering in her aunt's apartment. Thinking fast, the wet girl takes the name Rita from a handy movie poster. They bond quick and close. They start to solve a mystery together.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, where the cliches never quite gel, a young smug movie director (Justin Theroux) is finding out who really runs Hollywood and how careers are made and broken. Mr. Roque (Michael J. Anderson), a dwarf behind bulletproof glass, pulls the strings, a laconic Cowboy (Monty Montgomery) is the literal-minded enforcer. You see him twice if you're good, three times if you're bad.

Everybody in the movie seems him three times.

Mulholland Drive leaves us with more questions than anyone can be comfortable with -- yet it is one of those rare movies that incites the immediate desire to see it again.

Or does it? Some film-bit friends hate it, and while there are elaborate theories about it on the Internet, earnest minds spinning hard to resolve the thing into sense (Rita/Camilla and Betty/Diane are two expressions of the same self!), I'm content to believe that, as with both iterations of Twin Peaks, Lynch was making most of it up as he went along. It floated up from his unconscious. He probably doesn't know what to make of some of it any more than we do.

A popular interpretation is that the first half -- which is more than half -- is the fantasy of the suicidal Diane, who has hired a hit man to murder her lover-rival Camilla. In this fantasy, Diane recasts herself as the naive but talented Betty and saves Camilla from the hit man while erasing her memory of their doomed affair. So it's like a fresh start, only it's all a fantasy and when it dissipates, Diane is left alone with her guilt and the Lynchian vision

I can only guess, but I took Mulholland Drive as a depiction of curdled dream, another Norma Desmond Hollywood fantasy. Hollywood -- and America -- abuses and abases beauty.

On the other hand, this is a movie teeming with false starts, feints and unresolved narrative threads that might have actually gone somewhere had Lynch been able to unspool the season-long version. It's like a Rorschach test in that any sense you impose upon it is bound to say more about you and your state of mind than it is about what Lynch was actually trying to get at. "I don't know" is always a good answer when it's the truth.

Like any work open to interpretation, Mulholland Drive can safely be dismissed as pretentious claptrap. But for me, it remains the first genuinely great film of the 21st century, and the last great film of my Before.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 10/14/2018