Thousands of Arkansas children skip too much school to make academic progress each year, according to recent federal data.

At-risk youths struggle more with attendance, experts say -- especially children in foster care and those sent to juvenile court for truancy.

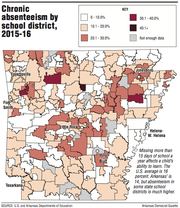

In 2015, 46 Arkansas school districts reported that at least 1 in 5 students were "chronically absent," according to U.S. Department of Education records.

Thirty schools, including Hot Springs High, Jacksonville High and Little Rock's Hall High, had at least 40 percent chronically-absent -- defined as missing at least 15 days in a school year -- students that year.

Overall, Arkansas' 14 percent chronically-absent rate placed the state just below the national average of 16 percent. Maryland topped the list, with more than 29 percent.

Chronic absenteeism is tied to graduation rates -- even more so than how many students receive free or reduced-price lunches or hold minority status in certain years, according to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette's analysis of the data.

[INTERACTIVE: Explore map showing past absence rates of Arkansas school districts]

Continually missing class is also linked to poor reading scores, especially in high school, the newspaper found.

Excessive absences for students, as young as kindergarten, takes away from social-emotional development that helps youths persevere and engage in learning, studies also show.

Ginny Blankenship, education policy director of Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, set out to look more closely at the relationship between the state's chronic absenteeism rates and a child's status as a foster kid or truant.

She soon learned -- because of incomplete data collection and information-sharing by municipalities, the court system and state agencies -- how difficult it is to get the full scope of the problem in Arkansas.

She did discover, however, that unstable foster family placements, delays in the transfer of school transcripts, recurring court hearings and court-ordered appointments contributed to chronic absenteeism for students involved in the foster care and juvenile court systems.

"We have to do a lot more to make sure these children get the education they deserve," she told the Democrat-Gazette. "Their future success and happiness depends on it."

A handful of organizations and educators across the state are working to curb chronic absenteeism. They say it will take changes in how governmental agencies share information and how juvenile court judges, social workers and school administrators work with families.

"We need to adjust if we're going to help," said Garland County Circuit Judge Wade Naramore, who presides over juvenile and certain family cases.

For instance, his court's diversion program has helped cut chronic absences, he said.

Chronically-absent students often end up in the state's Families In Need of Services (FINS) program, a legal avenue for addressing noncriminal-status offenses, including disobedience, truancy and running away.

A judge can order people involved in the program to show up for additional court hearings, and to complete counseling, parenting courses and other appointments. In some jurisdictions, these are scheduled without regard to parents' or students' school and work schedules. It can take months, even years for a judge to close a Families In Need of Services case.

Naramore said he had been receiving too many Families In Need of Services petitions from school administrators, often because of truancy. He then began "diverting" such cases from the courthouse. The parent and child were not summoned to juvenile court. Instead, court staffers went to the schools to meet with principals, teachers, students and parents to come up with a diversion plan consisting of goals laid out by caseworkers.

Garland County records show that 213 cases were diverted from the juvenile justice system in 2017. Almost all of those youths successfully finished the diversion program by meeting the outlined goals, Naramore said.

"Relationships are important," the judge said. "The schools know that. We had immediate buy-in from all seven districts. ... We all have to be constantly willing to re-evaluate to reflect the needs of our families."

SHARED CONCERNS

Arkansas doesn't have a standard way to measure school absences, and no one is officially counting how often foster and Families In Need of Services kids miss class, according to Blankenship's study, "Reducing Chronic Absenteeism for Children in Foster Care and FINS," published in September.

Because of the lack of data, the Arkansas Advocates chronic absenteeism report relies, in part, on anecdotal evidence. Interviews with school leaders confirmed that children in foster care miss class because of inconveniently scheduled court hearings, parental visitations and traveling long distances to get to school, especially in rural areas.

National research echoes their remarks.

Students in foster care miss school twice as often as their peers, with absences increasing as the students grow older, a 2013 study by the Children's Hospital in Philadelphia found. Unstable family placements cause kids to jump from school to school about twice a year, researchers concluded in a 2013 Child Youth Services Review journal article.

Arkansas officials said they're trying to address issues of incomplete data and educational stability for these students.

"Like advocates, we share the same concern," said Mischa Martin, director the Division of Children and Family Services.

In the past year, the division, a unit of the Department of Human Services, began tracking when a Families In Need of Services petition prompted a child's removal from home and included those numbers in the agency's quarterly reports, Martin said.

The division's reports don't include information specific to chronic absenteeism.

Arkansas law requires that foster students remain in their original schools whenever possible. However, the state has 1,600 foster care homes for the roughly 5,000 children in foster care, often leading to placements that force a switch of school districts.

We "have a vital role in working with the community and schools to ensure that children can remain in their school and ensure as few absences as possible," Martin said.

"But in some cases it is not in the child's best interest to have to travel a long distance to the school of origin. We strive to keep a child in his or her home school, but an appropriate placement option is not always available in the same school district or even county."

The Children and Family Services Division has seen a "significant increase" in educational neglect cases since 2015, Martin also said. Educational neglect occurs when a parent or guardian fails to provide a child's basic needs regarding schooling.

In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2015, only about 3 percent of the division's cases -- 1,095 out of 33,675 -- dealt with educational neglect. But within three years that jumped to about 3,100 of 35,856 cases related to educational neglect, almost 9 percent of the agency's entire caseload.

Tracking chronic absences for Families In Need of Services and foster students shouldn't just fall on the schools, Blankenship says.

In her report, she suggested that the Administrative Office of the Courts track who files Families In Need of Services petitions and why, what services are ordered and the educational outcomes of those cases.

Courts, the Human Services Department and the state Department of Education should coordinate their data systems into a "longitudinal database," the report recommended.

That way the academic progress and attendance of foster care and Families In Need of Services students is better understood, Blankenship wrote.

Building a longitudinal database takes a lot of work, but it will help leaders figure out how to better support children and how to use taxpayer dollars more effectively, said Susan Harriman, executive director of Forward Arkansas.

A public-private initiative focused on educational policy, Forward Arkansas was created by the state Board of Education, the Walton Family Foundation and the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation in 2014.

The group is working to put together a longitudinal database in hopes that its use will curb chronic absences.

Among sorting out the technical challenges -- "coordinating data among diverse systems of data is very complicated," Harriman says -- of such a project, the group must be mindful of federal and state privacy laws.

She believes it's worth the effort. With wider data, officials can figure out which factors help children succeed, which cause more harm and what is most effective in buffering children from the things that cause harm.

"Good data makes good policy," Harriman said. "We can ask questions with it. We can see nuances over time. ... It gives policymakers and decision-makers facts to make better decisions about investments and programs that we have."

'LACK OF COORDINATION'

The Families In Need of Services system -- the very program designed to help truant students -- is often too slow in handling cases of chronic absenteeism and often contributes to kids missing more class, Blankenship's research found.

"The lack of coordination among stakeholders is a major problem," she wrote. "When a FINS petition is filed, the court doesn't reach out to ask the [school] district about the student."

She also cites concerns raised by local educators during interviews.

"Once upon a time we had a district staff person to make these connections for us; however, now it is a very slow local process," one elementary school principal told her.

"I wouldn't necessarily say we have a good model," the report quotes an assistant principal of a Northwest Arkansas high school saying. "We have FINS paperwork that we fill out and send to the local court system, but it usually takes months before a student has a court date. In the interim is valuable [class] time that the student continues to miss."

Across the state, circuit judges saw 6,705 Families In Need of Services cases in 2016 and 4,974 cases in 2014, about a 35 percent increase, Administrative Office of the Court records show. Between 2012 and 2016, such cases made up about 26 percent of all juvenile cases -- when tallying Families In Need of Services, delinquency and dependency-neglect cases.

More schools, juvenile courts, families and caseworkers need to coordinate their efforts so that such students receive the support and attention needed to stay in school, Blankenship told the newspaper.

That means making sure court-ordered appointments don't bleed into time set aside for class or extracurriculars, she explained.

School districts can identify foster care and Families In Need of Services students and provide intensive in- and after-school programs so that they can read on level and graduate on time, she also said. Districts should assign a Families In Need of Services liaison to work with those children, just as they do for foster students, she said.

Arkansas' juvenile code about Families In Need of Services is murky, unlike statutes pertaining to foster care, and offers few guidelines on how to handle such cases.

The way Families In Need of Services cases are handled hinges on the availability of social services, often negatively affecting children in rural, high-poverty places, previous Democrat-Gazette investigations on the Families In Need of Services and juvenile probation systems found.

It also depends on how judges define disobedience, Blankenship's report found.

"Judges have wide latitude in determining how to handle FINS cases -- and FINS families have very few rights," she wrote. "Most alarmingly, the law allows the state to immediately remove a child from his or her home in FINS cases, without the same formal process in a dependency-neglect case."

This reduces a Families In Need of Services kid's chance for educational stability, she asserted. She recommended that judges rely more on alternatives to courts, like the diversion initiative established by Naramore, and help families receive more treatment or counseling.

Robert Balfanz, a Johns Hopkins University professor who oversaw an expansive study on chronic absenteeism over the past 10 years, also says that blaming parents doesn't solve the problem.

"The stigma and adversarial nature of investigations can make parents more resistant to help," his study noted.

'MORE HUMAN'

For the first time in his career, Drew Shover, Benton County's probation supervisor, said he's "seen something positive being done to address absenteeism and truancies."

The county and school administrators have introduced several initiatives that work with families to get kids to class, Shover said.

For instance, Families in Need of Services kids can work with juvenile officers on Saturdays and complete credit recovery courses that make up for missed lessons. They also created a weekend group that taught life skills to students.

About 38 percent of Families In Need of Services petitions, many of which stem from truancies, are diverted from ever going to court, Shover added.

Court staffers also attend school district meetings and update teachers about students who are involved with the court system, including coming court hearings and appointments, he said.

The Rogers School District made changes, too. It hired staffers, including bilingual speakers, to directly call families when a student is marked absent, so they were able to find out why the child skipped school. And administrators cordoned off the parking lot so students would have to talk to a school employee before driving off campus during the day.

The Arkansas Advocates report describes Benton County as a "bright spot" in the state, where the Families In Need of Services program is "less punitive and more about helping children" and officials from different agencies collaborate more often. The report also acknowledged Garland County's efforts.

"It's a more human approach to the problem," Shover said.

"That's important," he added. "Sometimes you have a kid put on FINS for truancy. And then you start going deep into the system and you forget about why the kid started in the system in the first place."

SundayMonday on 10/21/2018