An Atlanta man who must repay millions to swindled investors received licenses to operate two Arkansas nursing homes, exposing shortcomings in the state's vetting of potential providers, an Arkansas Democrat-Gazette investigation found.

The backgrounds and qualifications of incoming nursing home operators have generated heightened attention since the collapse of Skyline Health Care, a national chain that was licensed to operate 10% of the state's 25,600 nursing home capacity when it failed last spring.

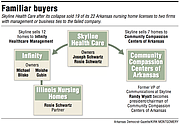

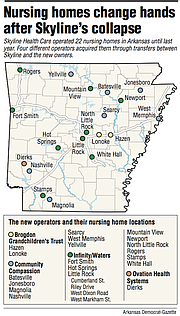

Skyline emerged from obscurity around 2015 to rapidly acquire more than 100 facilities across several states -- 22 in Arkansas -- before it cratered, its owners claiming insolvency.

The chain's sudden collapse sent public health officials here and in other states scrambling to avoid evacuating Skyline nursing homes of thousands of frail residents.

Against that backdrop, the Democrat-Gazette this year began reviewing the state's transfer of former Skyline licenses to new operators. The newspaper learned:

• The Arkansas Department of Human Services was unaware of an $83.1 million fraud judgment in 2015 against new licensee Christopher Brogdon of Atlanta until the newspaper asked about it, according to spokesman Amy Webb. Webb called the finding "concerning."

• Arkansas approved the transfer of 19 other former Skyline licenses to two firms with business or management ties to the failed company, even after the state attorney general's office raised objections.

• Federal and state investigators grew alarmed with how the Human Services Department responded to the crisis. One federal agent asked whether state officials had been corrupted.

• State officials have little flexibility when it comes to vetting incoming providers, Webb said. Laws restrict the reasons for denying an applicant and limit insight into operators' finances and backgrounds.

• While at least one other state changed its laws after Skyline's failure, Arkansas has not yet addressed a system that allowed an out-of-state operator, Skyline, to quickly acquire and then jeopardize 1 in 10 of its licensed nursing home beds.

In a statement for this article, an advocate for nursing home residents said the Skyline ordeal is "only a small part of a much bigger problem" and called on Gov. Asa Hutchinson to "take a hard look at how nursing home licenses are handed out in this state."

"Families need to know exactly what the state of Arkansas is doing to make sure that whoever applies for a nursing home license has both the experience and the financial wherewithal to take care of the residents," said the advocate, Martha Deaver, president of Arkansas Advocates for Nursing Home Residents.

Webb defended Arkansas' approach to the overarching crisis as "thoughtful and thorough in a really difficult situation."

"We wanted to make the right decisions for the residents, [to] make sure residents were safe and well cared for," Webb said. "They were our priority. And we feel like we made the best and most appropriate decisions."

SKYLINE'S DEMISE

Skyline's rise was swift; its fall even swifter.

Joseph Schwartz, a longtime insurance broker who specialized in the health care industry, founded Skyline in 2005. He ran it from an office atop a Wood-Ridge, N.J., pizza parlor, according to news reports.

In its first decade, Skyline owned six health care facilities, according to a biography Schwartz provided to Pennsylvania regulators, later published by Philly.com, the website for The Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News.

Beginning in 2015, Skyline acquired more than 70 nursing homes, most over a one-year period, according to the document.

A former Arkansas spokesman for Skyline said the company operated 114 facilities nationwide at its peak.

On March 23, 2018, a Friday, Nebraska seized 21 Skyline nursing homes after learning that day that the company would not be able to make payroll. Within a week, Kansas moved to seize 15 Skyline nursing homes.

South Dakota and Pennsylvania followed afterward, taking a combined 28 nursing homes from the company by May 2, according to news reports.

Arkansas officials assumed control over just two of Skyline's nursing homes on May 4 through local court orders and appointed an Arkansas provider to manage the facilities in Hazen and Dierks.

The state had not taken over a nursing home in more than three decades.

Both properties had lost access to credit, meaning they were at risk of not being able to pay for necessities such as food or medical supplies, Webb said.

The company's other 19 properties still had lines of credit, so state officials decided to increase monitoring at those locations -- sending staff members to each one at least once a week -- instead of seizing them, Webb said. Skyline had already sold one of its licenses at this point.

Illinois-based Infinity Healthcare Management ultimately contracted with Skyline to temporarily manage the 19 homes, the agreement shows.

The approach diverged from other states. Months later, investigators probing Skyline expressed puzzlement over Arkansas' decision to seize only two of Skyline's homes.

Webb said the 19 other homes, under stricter monitoring, were better run after Infinity stepped in.

"There was food," Webb said. "The employees got paid. The vendors got paid. And [residents] were well cared for. At the end of the day, those are the really important things to us that we want to see at a facility. And we did see that with Infinity."

Skyline simultaneously worked to find buyers for its remaining facilities. The Human Services Department approved the last of the licensing transfers in January.

The outcome sparked more questions.

BROGDON TRUST

A trust managed by Brogdon, the Atlanta businessman, holds 100 percent interest in two newly formed limited liability corporations (LLCs) licensed to operate two former Skyline facilities in Hazen and Lonoke.

The trust acquired the Lonoke license in February 2018, weeks before Skyline's problems exploded into public view. The trust received the Hazen license in September, while Skyline was offloading all of its licenses.

Brogdon has a public track record of legal troubles. Yet, Arkansas officials detected none when they ran a background check on him, according to Webb.

Such background checks flag criminal convictions or operators who are on interstate lists of excluded providers. But they do not pick up civil cases or criminal charges that were dropped as part of a settlement, Webb said.

Even if officials had known of Brogdon's background, they may have been powerless to deny him the licenses, Webb said. That's because the state's default position is to approve change-of-ownership transfers unless an applicant meets one of four specific conditions set out in state law.

Arkansas Code Ann. 20-10-224 says the department "may deny a license" if an applicant has a felony conviction, a license revocation in the past three years, runs facilities that had serious long-term care violations, or if other facilities failed to be in "substantial compliance" with standards in the past year.

Twenty years ago, Brogdon and a partner faced several criminal charges -- eight total counts of elder abuse, racketeering, Medicaid fraud and grand theft -- related to resident care at a Gainesville, Fla., nursing home they operated.

Florida prosecutors dropped the charges against the duo in January 2000, court records show. Brogdon's dismissal sheet lists the reason as "2T," which means to be refiled later, according to the former state's attorney who signed the document. The charges were never refiled.

Neither the state attorney who dismissed the case, Rod W. Smith, nor the prosecutor who filed the charges, Greg McMahon, could specifically recall why the case was dropped.

McMahon, who was on Smith's staff, vividly recalled details of the charges and said he believed investigators had enough evidence to win a conviction. But he said he remembered nothing about the dismissal.

"My obvious decision as to charging [Brogdon] was to keep him out of Florida, but also to keep him in jail," McMahon said.

Brogdon's attorneys had argued for dismissal in court filings, saying investigators had not proven that Brogdon was involved in day-to-day management of the nursing home.

An October 2018 report in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, citing records not found in Brogdon's individual criminal case file, said Brogdon-affiliated companies turned over operations of the Gainesville facility to a new firm and agreed to pay a $377,000 fine before the dismissal.

After the Florida case dissolved, Brogdon built a network of nursing homes. He was president and chairman of Global Healthcare REIT, as well as vice chairman and acquisitions chief for AdCare Health Systems, a publicly traded company that owned several nursing homes in Arkansas until 2016.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission sued Brogdon for securities fraud in November 2015. One month later, a federal judge ordered him to repay investors in 19 bond and private financing offerings.

The SEC complaint accused him of using the money he raised for personal gain and to prop up business interests that were outside the scope of the borrowing. It said Brogdon misled investors in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities as far back as 2000.

The court deemed Brogdon unfit to run publicly traded companies and barred him from management or director roles at firms that report to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

A phone number listed for Brogdon in the Arkansas change-of-ownership application is not a working number. An attorney representing him in the SEC case did not respond to emails.

Today, a trust managed by Brogdon -- called the Brogdon Grandchildren's Trust -- has contracted with a for-profit company, owned by Brogdon, to provide management services at both of its Arkansas facilities.

Brogdon signed each of the two management contracts on behalf of both the trust and the for-profit company, called Marsh Pointe Management LLC. The deals give Marsh Pointe, in which Brogdon is the sole member, 5 percent of the Lonoke nursing home's gross revenue and 3 percent of the Hazen home's gross revenue, the agreements show.

Aside from the two Arkansas facilities, Brogdon and his wife are affiliated with eight other nursing homes as stockholders or officers, all in Oklahoma, according to a list provided by the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

The Brogdons' affiliation with those facilities dates back to 2011 and 2014, before the SEC complaint, according to a Medicare.gov database.

Of the other 20 Arkansas nursing homes Skyline once operated, one went to Ovation Health Systems, co-owned by Anthony and Bryan Adams of Conway.

The remaining 19 were divided between two firms with direct connections to Skyline -- seven to a startup nonprofit called Community Compassion Centers of Arkansas and 12 to Infinity, the Illinois management company, records show.

'THE GRINDER'

Executives of both firms distanced themselves from Skyline in interviews with the Democrat-Gazette.

Community Compassion president and chairman Randy Wyatt, a Little Rock native, worked for Skyline as an executive vice president for public affairs.

In that role Wyatt communicated with local communities, public officials and the media on the company's behalf.

He also brokered a meeting between Skyline executives and Attorney General Leslie Rutledge's office, he said.

Rutledge's office "had some questions about some issues that were going on and wanted to meet" in late 2017, Wyatt said, adding that he didn't remember the specific issue.

In a series of four agreements with the attorney general's office, from April 2017 to May 2018, Skyline agreed to pay $205,000 in civil fines and staff training costs to settle 12 investigations by Rutledge's office into poor resident care, records show.

For context, Rutledge's office fined all other nursing home operators $492,000 in 2017 and 2018.

Wyatt said he left Skyline in February 2018 after learning that the company did not pay for his health insurance despite deducting premiums from his paycheck.

Wyatt learned that after being stuck with a $25,000 medical bill, he said. Several other employees were similarly burdened with large bills they didn't expect, he said.

"That was the last straw. They hurt people," Wyatt said, adding that Skyline's owners "are not people I will associate with ever again."

Meanwhile, Infinity -- operating in Arkansas under the brand name "Waters" -- had long-standing business relationships with the Schwartz family that owned Skyline.

Infinity's principals, Michael Blisko and Moishe Gubin, partnered with Schwartz's wife, Rosie, in two of their 14 Illinois nursing homes, according to that state's records. Rosie Schwartz held 30% and 20% interest in those properties, the records show.

Arkansas officials delayed the ownership transfers for months, an abnormally long time, according to Webb and Gubin.

The state put the company through "the grinder," Gubin said recently.

One of the reasons for the delay "was relationships with the Schwartzes," Webb said.

Human Services Department officials learned that Schwartz family members held interest in Infinity; the state asked that the Schwartzes divest before the licensing transfer, Webb said. They complied, she said.

"We requested that they divest because we weren't going to do business if it was going to be similar to Skyline," Webb said. "It was certainly a concern for us. But we saw [Infinity] acting in good faith."

Gubin said that Infinity, which operates more than 70 properties across five states, has a strong reputation nationwide.

"We have our own track record that stands on its own," Gubin said.

CONCERN EXPRESSED

Arkansas' approach to the national Skyline problem confounded investigators.

An agent in the federal human services agency's inspector general's office asked whether "public corruption or inappropriate influence" explained Arkansas officials' approach, Deputy Attorney General Lloyd Warford wrote last August in an email to state Medicaid Inspector General Elizabeth Smith.

Warford paraphrased the federal agent's concern and said he was opening an investigative case on Skyline in the email, which the newspaper obtained from the Arkansas Human Services Department through an open-records request.

Among 12 questions the Democrat-Gazette emailed to Rutledge's office this month was whether Warford was concerned about corruption within the Human Services Department during the Skyline crisis.

"The emails available speak for themselves and any further correspondence constitute the attorney general's unpublished memoranda, working papers and correspondence, and are exempt from disclosure," communications director Amanda Priest replied.

Priest provided a similar response for seven of the newspaper's questions, though she did confirm that the office's fraud investigation into Skyline is ongoing.

Also last August, Warford told Human Services Director Cindy Gillespie by email that Rutledge's office was concerned about the pending license transfers. He cited a conference call with Nebraska and federal officials concerning an unidentified ex-Skyline director in that state who moved to a company that was acquiring the Arkansas licenses.

"I was instructed to advise you that the Attorney General's Office is opposed to allowing the transfer to occur if the facts as presented [in the call] are correct," Warford wrote, adding that the office would help the department litigate if the denied applicant filed suit.

Warford did not name the company in the email. Both Infinity and Community Compassion by then had notified Arkansas officials of their intent to buy some of the Skyline homes.

When asked whether Warford believes the Human Services Department should have approved the change-of-ownership applications, Priest simply referred to Arkansas Code Ann. 20-10-224, which specifies the criteria the department may consider when reviewing application packets.

Rutledge's office "did express concern, but they did not give us grounds for denial," Webb said.

"I absolutely do not think there was anything untoward in how we handled it," Webb said. "What is important to know about the Skyline situation is it was not just one person making decisions. There was a whole group of people together following this very closely."

ROUTINE PRACTICE

Officials did not push new legislation related to the change-of-ownership process in the recently concluded legislative session, but Webb signaled openness to addressing the laws moving forward.

"I don't think we'd be opposed to looking at the [change-of-ownership] statutes and making changes," Webb said. "It's just not something we've done at this point, yet."

The Arkansas Health Care Association, which primarily represents nursing homes, is open to giving the state more authority during the vetting process, Executive Director Rachel Bunch said.

"We want that to be done correctly, and we're supportive of appropriate vetting," Bunch said. "We're trying to look at other states to see what they're doing ... so we can be part of that conversation if [the Human Services Department] decides to go that route."

In Kansas, where officials took over all 15 Skyline nursing homes last year, the Legislature passed a bill this month specifically in response to the crisis, officials said.

The new law requires stricter disclosure of applicants' finances, including a detailed budget for the first year of operation and evidence the applicant has access to sufficient "working capital." It also bars any operator of seized homes from obtaining a license for 10 years.

"We don't want these types of operators in the state," said Kim Lynch, chief counsel in the Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services.

As the Skyline saga played out in Arkansas, one key point of contention between Rutledge's office and the Human Services Department emerged, according to emails: the lack of a criminal fraud investigation.

Craig Cloud, the Human Services Department official over provider quality assurance, said at an early 2018 meeting that included Rutledge that her office would receive a fraud referral within a week, according to one of Warford's emails. That never happened.

Cloud was unavailable for an interview for this article, Webb said.

Ultimately, the department initiated a "recoupment" against Skyline for $4.7 million, essentially an administrative remedy rather than a criminal charge.

Medicaid payment rates are based on costs nursing homes report to the state for resident care. Skyline in this case was accused of inflating its expenses through the long-term use of a staffing contract company, Webb said.

Asked why this didn't constitute fraud, Webb said it can be difficult to prove intent. The law is open to interpretation, she said.

State officials saw it one way, and Skyline saw it another, so they resolved the problem by taking back the overpayment, a routine practice, she said.

Warford, the deputy attorney general, saw a different angle.

"I don't think DHS has anyone who really understands what fraud looks like," he wrote in an August email to the state's Medicaid inspector general, using the acronym for Arkansas' largest agency. "Does DHS think Skyline did this by accident here in Arkansas?"

Information for this article was contributed by Bobby Ampezzan for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

SundayMonday on 04/28/2019