There was excitement throughout Mississippi County when the federal government decided during World War II to create the Blytheville Army Air Field.

Civic leaders claimed that Mississippi County produced more cotton than any county in America. Businesses were doing well, and the population was growing. It had soared from 30,468 residents in the 1910 census to 80,217 by the 1940 census as virgin hardwood timber was cleared, land was drained, and cotton was planted.

Those fields required the labor of thousands of sharecroppers and tenant farmers. They chopped the cotton by hand in the summer and picked it by hand in the fall.

The airbase would add to the county’s growth.

A 2,600-acre tract was selected, and the base was activated on June 10, 1942.

Seven sites in Arkansas were chosen by the federal government for pilot training. Blytheville and Stuttgart had advanced twin-engine flying schools. Contract primary flying schools were at Camden, Helena and Pine Bluff. Newport and Walnut Ridge had basic flying schools.

“Mississippi County was a prime location because of its close proximity to the Mississippi River, where supplies could easily be shipped in,” Jillian Hartley writes for the Central Arkansas Library System’s Encyclopedia of Arkansas. “The airfield was used as the Southeastern Training Command’s flight training school. The flight school closed in October 1945 after the war ended. The airfield was then used as a processing center for military personnel who were being discharged at a rapid rate as the country demobilized. The War Assets Administration officially shut down the installation in 1946. Control of the land was transferred to the city of Blytheville.”

Mississippi County’s population peaked at 82,375 in the 1950 census. Additional good news came in the years that followed when the Strategic Air Command announced plans to convert the former Blytheville Army Air Field into Blytheville Air Force Base. The new base took up 3,771 acres and opened on July 19, 1955.

“The 461st Bombardment Wing was relocated to the newly constructed base from Hill Air Force Base in Utah,” Hartley writes. “By the following spring, the base was fully operational with three squadrons of B-57 bombers. … The 97th Bombardment Wing later assumed control of the base and brought with it the long-range B-52G bomber.

“The first bomber, named The City of Blytheville, arrived in January 1960. In addition to the B-52G, the base also housed the KC-135A Stratotanker aerial refueling aircraft. It was also used by the 42nd Strategic Aerospace Division during the 1960s and early 1970s.”

As the Cold War heated up, two major things were happening in Mississippi County. The first was the mechanization of agriculture. The mechanical cotton picker, improved seed varieties and better herbicides and insecticides meant that most of the sharecroppers and tenant farmers were no longer needed. Many of them headed to the upper midwest, where the steel and automobile industries were thriving during the post-war boom.

Mississippi County’s population dropped to 62,060 by the 1970 census. That’s 20,000 fewer people than had lived there two decades earlier.

The second major development was the growth of Blytheville Air Force Base. While the county as a whole was losing population, Blytheville saw its population increase from 16,234 in the 1950 census to 24,752 in the 1970 census.

In October 1962, the 97th Bombardment Wing was placed on airborne alert during the Cuban missile crisis. SAC declared what was known as DEFCON II (defense readiness condition) for the first time. Two B-52G bombers, armed with nuclear weapons, were in the air.

“The surrounding communities benefited greatly from the military funding that poured into the base, as well as the cultural contributions of the base’s diverse military personnel,” Hartley writes. “The professional scientists, engineers and other military personnel who relocated to the base enhanced the ethnic and societal composition of the predominantly agricultural county.”

The name of the installation was changed to Eaker Air Force Base in 1988 to honor Lt. Gen. Ira Eaker for his contributions to the country. Just three years later, as the Cold War came to an end, Eaker Air Force Base topped the SAC list of base closures. The base closed on Dec. 15, 1992.

“The withdrawal of the last 3,500 airmen in December 1992 had an immediate impact on Mississippi County,” Hartley writes. “The Gosnell School District lost half of its enrollment. The local community college lost about 20 percent of its students. Mississippi County’s unemployment rate increased more than 5 percent the year after the base closed.”

By the 2010 census, Mississippi County’s population had fallen to 46,480 (down 36,000 since 1950) and Blytheville’s population had fallen to 15,620 (down 9,000 from 1970).

Enter Mary Gay Shipley.

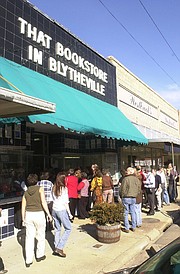

In the 1970s, Shipley was teaching school in her hometown of Blytheville when she decided that the city needed a bookstore. She opened a paperback exchange store affiliated with a Memphis group known as The Book Rack. She later found space in a former jewelry store on Main Street in 1976.

Since people around northeast Arkansas referred to her business simply as “that bookstore,” Shipley changed the name to That Bookstore in Blytheville in 1994.

Shipley was one of the few bookstore owners to host a signing for author John Grisham when Grisham came out with his first book. Grisham returned the favor by coming back to Blytheville each time he released a novel. People would come from Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Missouri, western Kentucky and southern Illinois to get their books signed in Blytheville by the ever-more-famous novelist.

In the process, That Bookstore in Blytheville became one of the best-known independent bookstores in the country, and Shipley became a legend among booksellers. She hosted hundreds of authors in Blytheville through the years.

“A champion of literacy, Shipley used the store to promote reading among local schoolchildren,” Tom Williams writes in a history of the bookstore. “Children’s reading materials—and educational toys and games—were located in the homey back room, complete with a stove and wooden floors. The back room also hosted reading groups, musical performances and author signings and readings. Authors signed their names on a series of wooden chairs. They often read from their work while seated in a rocking chair.

“Locals viewed the plethora of writers who visited Blytheville as fairly common, but it was quite remarkable when one considered that Blytheville had become a much-visited spot by writers from large and small publishing houses.”

Shipley sold the store in 2012 and retired. It was sold again in 2014 before closing in 2017. Andrew and Erin Carrington then bought the store, changed its name to Blytheville Book Company and reopened it down the street last year.

Shipley has a new mission: to create the National Cold War Museum on the grounds of what was once Eaker Air Force Base. Shipley chairs the nascent museum’s board and has set an aggressive fundraising goal of $20 million. She thinks it’s the kind of attraction that, if done well, will attract visitors from across the country.

That’s especially true now that more tourists are coming to Mississippi County to see the Johnny Cash boyhood home at Dyess, which has been restored by Arkansas State University, and the model Delta town of Wilson, being revitalized by wealthy investor Gaylon Lawrence Jr.

In 2016, Barry Harrison, who heads the Blytheville-Gosnell Regional Airport Authority, received a call from a National Park Service historian named Robie Lange. The historian wanted to know about the former alert center at the base, where pilots would stay with their bombers fueled just outside, ready to take off within minutes should a nuclear war begin.

“He told me that these alert centers played a big role during the Cold War era and that they needed to be saved,” Harrison says. “I decided it was time to do just that.”

The state helped fund a feasibility study in 2017. Harrison describes the results of that study as “very promising.”

Harrison, who served three four-year terms as Blytheville’s mayor from 1999-2011, knew Shipley was just the person he needed to drive the project forward. He already had seen her do things that people around Blytheville thought would never be accomplished.

Nonprofit status was obtained from the Internal Revenue Service, a committee was pulled together, and Shipley’s team went to work. The committee now has a conference call every week along with monthly meetings.

“We always want everything yesterday, but a process like this takes time to do well,” Shipley says. “We had to do a cost analysis. Earlier this year, we hosted what was known as an envisioning session. We’re now beginning the fundraising phase.”

Shipley and Harrison are confident they can raise $20 million to create a nationally known attraction. They’ve identified a building at the base that will be used for an initial exhibition while the money is raised to transform the alert center.

One of the documents handed out at the envisioning session included this quote from famous architect and planner Daniel Burnham: “Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans. Aim high in hope and work.”

After the base closed, the Blytheville-Gosnell Regional Airport Authority created what’s known as the Arkansas Aeroplex to redevelop part of the property. Aviation Repair Technologies established an operation in 2008 to do aircraft maintenance, disassembly and storage. Westminster Village of the Mid-South purchased some of the military housing and began a retirement community. A $2.5 million youth sports complex was built. An annual Christmas show known as the Lights of the Delta attracts people from throughout the region.

Harrison and Shipley find it amazing that no museum devoted to the Cold War exists. They think Blytheville is the best place to start one. They can even see a day when buildings at the former base will serve as the home of a National Cold War Center that would contain extensive archives. Lectures could be held there, and visiting scholars could be housed at such a facility.

“This will be the only one of the former alert centers that will be open to the public,” Shipley says. “That makes us unique.”

A walk through the alert center allows visitors to see the possibilities. There were nine parking positions for planes—five bombers and four tankers—just outside. There’s a briefing room with theater-style seats where an introductory film could be shown in such a museum. There’s a recreation hall with a basketball court and swimming pool outside. There are no steps attached to the building. There are only ramps. Personnel could have run at full speed toward their planes had a nuclear war begun.

Elsewhere on the grounds of the former base are bunkers where nuclear weapons were stored, the facility where guard dogs were kept and other reminders of the Cold War.

“We think we can attract 150,000 people per year,” Shipley says.

Some might scoff at that number, but Shipley has put Blytheville on the map before. Just ask John Grisham.