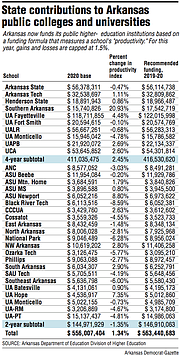

The 2019-20 academic year is the second in a row in which the state's public colleges and universities as a whole will receive more state money, after years of frozen funding that has left the state's higher-education institutions behind pre-recession levels.

This year also marks the first in which some schools will lose money after years of steady, if arguably insufficient, funding. Most schools -- 18 of 32 -- will lose money this year compared with their base funding.

The increase in state contributions is attributable to Arkansas' new formula for funding higher education. The formula measures school performance against previous years, multiplies the difference by the school's base funding and caps gains and losses. It redistributes funding from schools with productivity losses to those with productivity gains.

Overall, the schools' "productivity," according to the state's method of calculating it, increased. The state was 1.34% more "productive" during the 2015-2018 school years than during the 2014-2017 school years, although four of 10 public universities were less productive and 14 of 22 public community colleges were less productive.

The new productivity funding formula, which the state implemented as part of a national trend changing how higher-education institutions receive government money, is in its second year. It will be slightly different for the next year because of tweaks in how certain metrics are weighted.

The formula accounts for school "effectiveness," affordability, efficiency and research. "Effectiveness" includes the number of credentials awarded, the number of students reaching progression points, the number of students passing gateway courses and the success of transfer students.

Metrics are often weighted. For example, certificates of proficiency are multiplied by 0.5, and doctoral degrees are multiplied by 6. Schools also get to multiply progression figures for underserved race, income or academic backgrounds or for people from 25 to 54 years old by 0.29. Those metrics comprise only a certain percentage of a school's overall productivity score.

The formula caps funding gains and losses at 1.5% for each school. The caps will be 2% for the 2020-21 school year and will remain at that level indefinitely. The state won't provide less funding for higher education under the formula; lost funds from schools are redistributed to schools with productivity increases.

"We're trying to keep the drama to a minimum," said Maria Markham, director of the Arkansas Department of Education's Division of Higher Education. "Things like what happened in Alaska happen when you don't have any kind of cap."

The state of Alaska and local funding sources spend more than double the national average per student -- more than $16,000, compared with just more than $7,000 -- according to the College Board. (Arkansas spends slightly less than the average.)

Some argued that was a sign of the University of Alaska System's over-reliance on money from an oil-dependent state, while others contended it was a necessity in an extremely rural state. In an effort to reduce the state's deficit and increase an annual state resident payout to $3,000 without raising taxes, Alaska Gov. Michael J. Dunleavy cut the University of Alaska System's budget by $130 million for this fiscal year, according to articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The state Legislature cut another $6 million.

The cuts left students worried about losing state scholarships and affording school. Last week, regents moved to consolidate the system's three universities into one.

For years, Arkansas higher-education leaders requested funding based on school needs, largely factoring in the number of enrolled students. The amounts would have required tens of millions more dollars from the state's Legislature and were consistently rejected in favor of keeping the funding the same.

During that time, some schools grew by hundreds of students and others declined in student enrollment. That means schools' base funding, used in the formula, is calculated off a figure that assumes a different student population. Schools that now have higher enrollment may still receive significantly less money than schools that once had more students. However, students from underserved populations have always counted for more in funding formulas because of the higher cost of ensuring their success.

While implementing Act 148 of 2017, the Arkansas Legislature authorized a one-time cash influx of $9.4 million when it approved the productivity-based funding formula. This year's increase is entirely based on the formula -- $861,551 more than the $562,579,132 contributed last year.

The law prompted state higher-education leaders to change not just how they calculate needs but also how they track certain information. Markham called some of the schools' information a "hot mess" before leaders streamlined and cleaned the data.

For this year, the biggest dollar increase from base funding will go to the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville -- $3.3 million. The school increased its productivity almost 4.5%, largely by awarding more credentials and having more students hit major progression points, such as 15 credit hours or 30 credit hours. But because the university had an even larger incentive under the state's one-time cash influx -- $3.8 million -- last year, its state funding will actually be nearly half a million dollars less than last year, when it received $122.5 million.

The biggest loss from base funding -- and last year's funding -- is at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, which spent less money on research in recent years, spokeswoman Tracy Courage said. The school will lose $383,948, which was factored in during fiscal 2020 budget cuts this past spring. That means it will get about $56.3 million from the state.

"I believe ADHE recognized this as an unintended consequence of the current funding formula," Courage said in an emailed statement to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, "and I understand they are adjusting the formula so that small changes in the research expenditure metric do not have the unintended consequence of reducing the points an institution receives under the funding formula."

The biggest percentage increase among universities is at Southern Arkansas University, which had a 20.9% productivity increase. The university's index rise stands out next to all public higher-education institutions, none of which had increases of more than 8.8%. SAU was the only university to have a productivity increase that surpassed UA's 4.5% rise.

SAU awarded 54.8% more credentials during the 2015-18 school years, compared with the 2014-17 school years. The school awarded about 11,000 credentials -- up from about 7,000. More students hit major progression points, although fewer students passed gateway courses. The university will get $17.5 million from the state, up from close to $16 million.

Donna Allen, SAU's vice president for student affairs, attributed the large increase to a growth in credentials offered at the school during the past 10 years, as well as to graduates working in science, technology, engineering and math fields. The university also has added advisers and career and mental health counselors, Allen said, and has improved its graduation rate by 6.5%.

The university also grew by about 1,100 students between the fall of 2014 and the fall of 2017, which saw 4,643 students enrolled. The university enrolls a smaller number of high school students than most of Arkansas' other public universities, counting only 268 high school students among its enrollees last fall.

Among community colleges, Arkansas State University-Newport had the biggest productivity increase after improving in all effectiveness categories -- credentials awarded, students hitting major progression points, students passing gateway courses and transfer student success. The college's productivity index rose 8.8%. It will receive $921,406 above its base this year, and $252,458 more than last year, for a total of nearly $7 million.

In some states, schools can only gain money, not lose it.

But in Arkansas, the state implemented the recommendations of the Indiana-based Lumina Foundation, which has championed productivity funding models across the country, Markham said.

"Ours is probably the most aggressive that we've seen," Markham said. "Most places don't redistribute money among institutions."

But how can schools turn things around when they don't have as much money? Markham said the data can help them know what to do differently.

When schools lose money three years in a row, they must submit plans to reverse the losses. They won't lose any more money while officials attempt to right their ships.

A Section on 08/05/2019