Century-old minutes of American Legion meetings in Helena are providing some insight on the Elaine massacre, said Brian Mitchell, assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Joseph Alley, curator of the Helena Museum of Phillips County, said he found the minutes in early July in an American Legion ledger book. The book contains the minutes of Post 41's meetings from its inception in 1919, the year of the Elaine massacre, through 1925.

The Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history, according to an entry in the Central Arkansas Library System's Encyclopedia of Arkansas written by Grif Stockley. The riot stemmed from tense race relations and growing concerns about labor unions.

"A shooting incident that occurred at a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union escalated into mob violence on the part of the white people in Elaine and surrounding areas," wrote Stockley. "Although the exact number is unknown, estimates of the number of African Americans killed by whites range into the hundreds; five white people lost their lives."

Mitchell said the ledger book "sheds light on the post's involvement in the massacre from their own perspective."

"We know that the first interaction that the sharecroppers union had after the Hoop Spur shooting came from a group of deputized American Legion members who had just returned from World War I," he said.

"They were first mustered to arrest the shareholders in the union after the shooting in Hoop Spur but some led posses in the days that followed."

The find was announced in a news release from UALR.

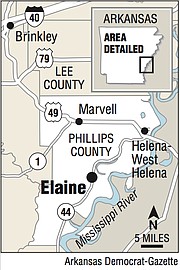

On the night of Sept. 30, 1919, about 100 black people, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of white landowners, attended a meeting of the union at a church in Hoop Spur, 3 miles north of Elaine, to try to get better payments for their cotton crops, Stockley wrote.

Armed guards were stationed outside the church. A shootout took place in front of the church between the black guards and three people, resulting in the death of W.A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and the wounding of Charles Pratt, Phillips County's white deputy sheriff, wrote Stockley.

The next morning, the Phillips County sheriff sent a posse to arrest those involved in the shooting, wrote Stockley. But a mob of 500 to 1,000 armed white people had gotten word of the shootout by then and swept through the area, killing many black people.

On Oct. 1, 1919, Phillips County authorities requested that federal troops be sent to Elaine. The troops arrived the next morning, and the white mobs began to leave the area, wrote Stockley.

Stories differ on who fired the first shot, but hundreds of black people were arrested in the wake of the massacre.

In the 1919 ledger book, under a section titled "Post in action," the entry reads: "On Oct. 1st, Wed., the members of the post were summonsed to the court house as a result of the assassination of Special Agent Adkins near Elaine Tues. night, Sept. 30th. Among those responding were James A. Tappan, Clinton Lee & Ira Proctor. They were among the first to arrive on the scene of the murder, and in the subsequent fighting with Negro rioters the first two were killed and the latter was seriously wounded but will recover."

Two weeks later, the American Legion post adopted "Resolutions of Respect to the Memory of James A. Tappan and Clinton Lee."

The first "whereas" read: "There has been an insurrection of Negroes in Phillips County, and the lives and property of our citizens have been placed in jeopardy."

"One of the things that minute book reveals are the efforts that were made by the general populace to ensure, even before trial, that the leaders of the Progressive Farmers and Household Workers Union would be sentenced to death," said Mitchell.

An account of an American Legion meeting on Oct. 19, 1920, indicates a vote was held and "motion carried to demand execution of Negroes convicted," said Alley, who was reading from the document.

"The same people who were in the mob that hunted down people during the massacre then made demands on the governor that the men would be given the death penalty," said Mitchell.

"They wanted the death penalty because they wanted to send an example for other sharecroppers that might consider legal action against them for stealing their wages."

"By Nov. 5, 1919, the first 12 black men given trials had been convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair," wrote Stockley. "As a result, 65 others quickly entered plea bargains and accepted sentences of up to 21 years for second-degree murder."

Ultimately, none of the 12 black defendants charged with murder was executed, and all 12 had been released as of 1925 after appeals to the state and U.S. supreme courts, wrote Stockley.

The ledger book is too fragile to display, but a digital copy has been made by the Arkansas State Archives. It has yet to be made available online.

Metro on 08/14/2019