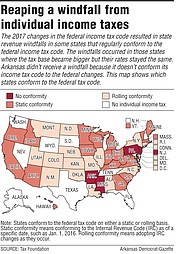

Many states in the country last year received a windfall of state tax revenue, thanks to changes brought on by the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

But Arkansas wasn't one of them.

"Some states have announced that they expect to experience a windfall in revenues as a result of the TCJA because those states' law conforms automatically to the Internal Revenue Code," said Paul Gehring, an assistant revenue commissioner for the state Department of Finance and Administration.

"Arkansas is not an automatic conformity state," he said. And, according to a department spokesman, the Arkansas Constitution won't allow automatic conformity.

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have rolling conformity with the Internal Revenue Code, meaning that they conform to relevant provisions of the new federal law automatically. Nineteen others conform when their laws are updated to adopt the new provisions by a specific date, the Tax Foundation said in a report last year.

States that made changes broadened their tax base and typically reaped a windfall if they kept their individual income tax rates the same, the foundation said.

A handful of states conform only selectively, incorporating certain federal provisions or definitions by reference, but omitting large swaths of the federal tax code and forgoing the use of federal definitions of income as their own starting points for calculation, the Tax Foundation reported. Those changes, if they occur, are made by lawmakers.

Arkansas is one of four states with selective conformity to the federal individual income tax code, according to the Tax Foundation. The others are Mississippi, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington and Wyoming don't levy individual income taxes, while New Hampshire and Tennessee tax only interest and dividends, according to the Tax Foundation.

After passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, the debate on tax overhaul shifted from Washington, D.C., to the states because states incorporate provisions of the new federal tax codes into their own tax codes to varying degrees, meaning the federal tax changes have implications for state tax revenue, according to the Tax Foundation. But the federal changes don't include the rates that states use to determine taxes.

"Because the base-broadening provisions of the new federal tax law often flow through to states, while the corresponding rate reductions do not, most states will experience a revenue increase from federal tax reform, although several states could see decreases, largely due to the new federal pass-through provisions," the Tax Foundation said.

The enactment of the federal tax overhaul at the end of 2017 was the most pressing and widely addressed tax issue during 2018 legislative sessions, said Jackson Brainerd, a policy specialist for the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Arkansas lawmakers are now meeting in a regular session that started Jan. 14. They will consider Gov. Asa Hutchinson's proposed cuts in state individual income taxes, but they won't be looking at conforming with certain 2017 federal changes that would raise an estimated $28 million a year.

WINDFALLS, TAX CUTS

States estimated that they stood to gain several million to hundreds of millions of additional state tax dollars because of their expanded state tax bases.

For example, New York projected increased revenue of $1.1 billion in fiscal 2019, while Vermont projected $30 million more the same year, according to the Tax Foundation.

Similar estimates have been made in fiscal estimates that accompany a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June 2017 that opened the door for states to start collecting sales taxes from out-of-state retailers without a physical presence in their state, Brainerd said in an article posted on the conference's website.

"The prospect of this new money seems to have given states an opportunity to look into cutting tax rates themselves, specifically for personal income and corporate taxes," Brainerd said.

Between 2008 and 2015, 14 states reduced personal income tax rates, and these cuts were frequently paired with increases in consumption taxes, he said.

"But now after a brief hiatus, income tax cuts are surging again," Brainerd wrote. "Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky and Missouri all enacted legislation to reduce personal and corporate income tax rates and at least seven other states considered cuts as well."

For example, Missouri eliminated the top income tax bracket of 5.9 percent for income of more than $9,000 and replaced it with a new top rate of 5.4 percent for income of more than $8,000, starting in tax year 2019, he said.

Missouri maintained a provision from a 2014 law that provides for a 0.1 percent reduction in tax rates annually, contingent on net revenue from the previous fiscal year exceeding the largest amount of general revenue collected in any of the three previous fiscal years by $150 million. Missouri also reduced the corporate income tax rate from 6.25 percent to 4 percent, starting in January 2020, Brainerd wrote.

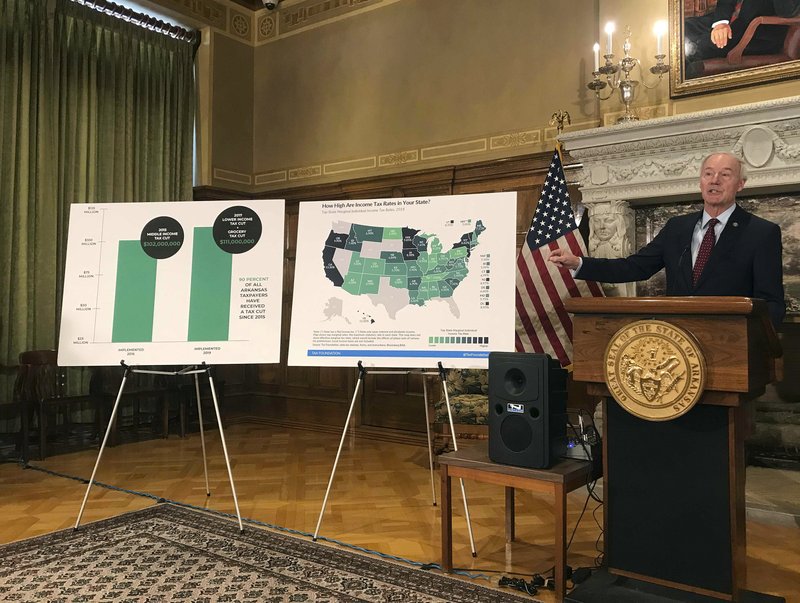

ARKANSAS CUT

In Arkansas, Hutchinson on Wednesday unveiled his latest plan to cut the state's top individual income tax rate from 6.9 percent to 5.9 percent. He described this as an effort to make the state more competitive in attracting industry, capital and talent.

The Republican governor said his plan would reduce the number of individual income tax rates in the upper-income tax table from six to three; trim the top rate from 6 percent to 5.9 percent in the middle-income tax table; be implemented over a two-year period; and reduce state tax revenue by about $97 million a year, after it's fully implemented.

The current top rate of 6.9 percent applies to people with at least $79,300 a year in 2018 taxable income, said Scott Hardin, a spokesman for the state Department of Finance and Administration. Under the latest proposal, the 5.9 percent rate in the upper-income tax table would apply to those making at least $80,500 a year.

The governor's plan also would reduce the maximum rate for the top tier of income in the middle-income tax table for individuals who make from $22,500 to $80,500 a year. In that table, a 5.9 percent income tax rate, rather than the current 6 percent, would be applied to the portion of income that is at least $37,500 a year.

In 2015 and 2017, the Legislature enacted the Republican governor's plans to cut individual income tax rates for people with up to $75,000 a year in taxable income. The cuts are collectively projected by state officials to reduce state revenue by about $150 million a year.

CONSTITUTIONAL LIMIT

Arkansas' tax code doesn't automatically conform to the federal tax code because "an unconstitutional delegation occurs when the General Assembly attempts to delegate the authority to tax an entity other than one of those specified in the Arkansas Constitution," Hardin said.

The Arkansas Legislature cannot delegate its power to tax or fix the tax rate except as provided under Article 2, Section 23, of the Arkansas Constitution, Hardin said.

Article 2, Section 23, states, "the General Assembly may delegate taxing power, with the necessary restriction, to the State's subordinate political and municipal corporations, to the extent of providing for their existence, maintenance and well being, but no further."

For example, the tax rates for a corporation's income may not be dependent on a federal law or rule that may be changed, Hardin said.

UNKNOWN EFFECT

Department of Finance and Administration officials "don't have an overall total of what would happen if we perfectly mirrored the federal code to my knowledge," he said.

Gehring, the assistant revenue commissioner, said, "Most notably, there are two areas that Arkansas is very far off from federal conformity.

"The first is the expensing of assets purchased by a business, and also depreciation," he said.

For example, the state would collect $94.5 million less in the first year and $106 million less in the second year if it adopted the federal provision for 100 percent of depreciation of qualifying assets so they may be written off completely in the year of purchase, said Joel DiPippa, legal counsel for the finance department's Revenue Division.

Gehring said, "We were, prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, not in conformity with the federal government just because of the amount of the revenue impact that would result if we were to become into conformity with the Internal Revenue Code.

"Following the Great Recession, a large part of Congress' efforts to jump-start the economy were to provide incentives for businesses to acquire and invest in capital improvements. The federal government is much more generous when it comes to expensing and depreciation of business expenses," he said.

PLAN SHELVED

In November, Hutchinson proposed changing the state income tax code to conform to certain changes in the federal income tax code to raise about $28.8 million a year in state revenue. The governor shelved that proposal last week. The proposed changes were related mostly to unreimbursed employee expenses and other miscellaneous expenses.

Last year, Gehring told the Legislature's tax overhaul task force that the $28.8 million raised could be used to help offset the estimated $192 million-a-year reduction in state revenue that would result from a now-abandoned income tax cut of the governor's.

Hutchinson's decision to shelve these proposals to conform to the federal code were based on discussions between his office and lawmakers, said his spokesman, J.R. Davis.

"For the time being, there is no plan to push for federal conformity to our tax code at this point," Davis said.

Senate Revenue and Taxation Committee Chairman Jonathan Dismang, R-Searcy, said in an interview, "Originally, we had conformity [along with Hutchinson's previous tax plan], and it made sense because you were increasing the standard deduction with that" earlier individual income tax cut plan.

"And that kind of coincided with what the feds did, so they capped some of the itemized deductions but increased the standard deduction," he said. "However, as the [governor's] plan changed to the '5.9 plan,' we were no longer increasing that standard deduction, and it didn't make as much sense to put those limitations in place on the itemized deductions schedule," said Dismang, who is an accountant.

"One more piece to that is the limitations [on itemized deductions] that the feds put in place are temporary and have a sunset date and will have to be renewed or extended at some point, so it wasn't a permanent change in the federal tax code," he said.

SundayMonday on 02/03/2019