Happy bicentennial, Arkansas! You don't look a day over 190.

OK, settle down. This isn't the state's 200th birthday. That's not until June 15, 2036.

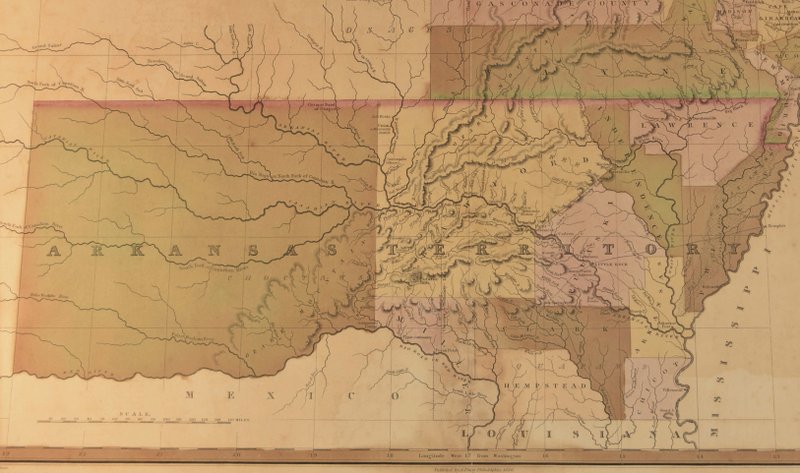

Saturday, though, is the 200th anniversary of the creation by the United States government of a little space called the Arkansas Territory. Stretching from the bottom of Missouri to the top of Louisiana, and from the Mississippi River almost all the way to the Rocky Mountains, the territory came to be on March 2, 1819.

The Department of Arkansas Heritage will have a bicentennial celebration at 10 a.m. Friday on the second floor rotunda of the state Capitol with birthday cake, history displays and special activities. The Arkansas State Archives will distribute free territory maps, and Gov. Asa Hutchinson will speak.

[RELATED: Ways to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Arkansas Territory]

So, how did this piece of earth become part of this nation?

Well, let's start with the Louisiana Purchase, the 1803 land deal between the United States and France in which the fledgling country paid about $15 million for around 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River.

In the aftermath, Arkansas was part of the District of Louisiana. In 1805, it became Louisiana Territory with a capital in St. Louis.

"The first official use of the name Arkansas came in 1806, when the southern portion of New Madrid County in Louisiana Territory was designated as the District of Arkansas. In 1813, it became Arkansas County in Missouri Territory," according to an entry in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture written by Charles Bolton, professor emeritus of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Bolton is an expert on this period in Arkansas' history. He's the author of the 1993 book Territorial Ambition: Land and Society in Arkansas 1800-1840 and of Arkansas 1800-1860: Remote and Restless from 1998.

It was a sleepy sort of place at the time, Bolton says during an interview amid a bustling crowd in search of caffeine at Mylo Coffee Co. in Little Rock.

Arkansas Post, the first significant European establishment in Arkansas, had been active since 1686 and was a trade headquarters for the Spanish and French. Located between New Orleans and St. Louis, it was a convenient stop for travelers and traders.

"There were a few English speaking settlers who had moved into Arkansas even before the Louisiana Purchase. A few more came after that, but Arkansas Post had a white population of about 200-300 people. It didn't really change much."

In 1805, settlers and slaves numbered around 500 people.

Things started to change in 1810.

'SIGNIFICANT MIGRATION'

"A significant migration out of Missouri settled the interior portions of Arkansas and provided a basis for the organization of the area as a separate territory in 1819," Bolton writes in Territorial Ambition.

Immigrants were entering the territory via the Southwest Trail, an Indian path also used by the French and Spanish that stretched diagonally from Arkansas' northeast corner down to its southwest corner. The trail connected people to places other than Arkansas Post and its environs.

"You've got these people coming down the Southwest Trail and they settle a place called Poke Bayou that becomes Batesville," Bolton says. "And people keep coming. Where the trail crosses the Arkansas River near Cadron there was a settlement by 1810. Between here and Cadron there were maybe 100 or so people living as early as 1810."

The trail also passed through Davidsonville, site of the state's first post office, established in 1815. Davidsonville, which was abandoned by the 1830s, is now Davidsonville Historic State Park.

The census of 1810, which covered only eastern Arkansas and not other populated areas along the Southwest Trail, counted 1,062 white settlers and their few slaves.

Cherisse Jones-Branch, history professor at Arkansas State University at Jonesboro, says that enslaved people had been here since at least 1723.

"They could have come from anywhere, particularly after the Revolutionary War. It's entirely likely they were with the French and Spanish. It's also likely they were sold from the upper South — Virginia, Maryland and that area."

By 1820, she says, the population included 1,617 enslaved black people and 59 free ones.

The War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom, which lasted until 1815, helped stall the territory's progress as attention was diverted to the east, Bolton says.

After the war, though, western migration was inevitable.

'DEMAND FOR LAND'

"There is this pent up demand for land, and that's when people really begin to come down the Ohio River Valley," Bolton says. "They settled a lot of Kentucky. Ohio has become a state. Indiana, Illinois have become states. People are looking for land, and Missouri is a real desirable place. Now this pattern of people coming down the Southwest Trail becomes much more important."

When Missouri applied for statehood in 1819, the northern border of what would become Arkansas Territory was set.

"If Arkansas wasn't going to be part of Missouri anymore, it had to be something else," Bolton says.

Congress created the territory in 1819, with Arkansas Post as its capital. Slavery was nearly banned in the territory, but wasn't. Even if it had been, Bolton believes, slaveholders would have found a way to persist.

"That land in eastern Arkansas is some of the best cotton land in the world. Keeping people from crossing into Arkansas and growing cotton and doing it with slavery would have been impossible," he says.

James Miller of New Hampshire, a brigadier general during the War of 1812, was appointed the first governor of the Arkansas Territory and served as superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Arkansas Territory. Kentucky-born Robert Crittenden was named the first secretary of the territory and was often acting governor in Miller's frequent absences.

Also in 1819, William Woodruff began printing the Arkansas Gazette at Arkansas Post and later in Little Rock, which became the territorial capital June 1, 1821.

Bolton stresses also the impact of the steamboat, which brought goods and people from the east to the wild Arkansas land and pulled it into the nation's economic ranks.

"The earliest steamboat got to Arkansas Post around 1819, and a year or so later was at Little Rock," he says. "It was tremendously important. Arkansas was in the middle of nowhere to a degree ... it was a frontier with all sorts of violence and bandits, and the steamboat made Arkansas. The larger point is that the development of the entire lower Mississippi valley was made possible by the steamboat ... it integrated the Mississippi valley into the national economy."

NUMBERS DWINDLED

The numbers of indigenous people, like the Quapaw, Caddo and Osage, had dwindled by 1819. The western Cherokee, though, flourished. They left the St. Francis River Valley around the time of the New Madrid earthquakes in 1811-1812 and settled around present-day Russellville.

"They built homes, cleared fields, and developed a flourishing society that may have numbered as many as 5,000 people by 1819," Bolton writes at encyclopediaofarkansas.net.

Woodruff's Gazette regularly railed against the Cherokee presence.

"White people wanted the land," Bolton says at the coffee shop. "Someone in the Cherokee settlement wrote a letter to the Gazette saying, 'Well, we may be uncivilized, but we have two churches, a school ...' They made it clear that they were living better than most of the people in Little Rock. It was very funny."

By 1828, the Cherokee, under pressure from the territorial government, relinquished their claims in Arkansas and moved into Indian Territory (which became Oklahoma).

Bolton dedicates a chapter to the role of women in Territorial Ambition, which includes some less-than-flattering descriptions from male visitors of that time.

Jones-Branch, who co-edited the 2018 book Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, says, "Living was so difficult here, their labors in this frontier space are important. They're contributing to the economy and in some cases owning property, often because they've inherited their husband's property. They're not just sitting home knitting, they're occupying very critical roles."

A BOOM TIME

The 1820s-'30s were a boom time for the state's population.

"There is a massive migration, and that changes the whole character of Arkansas," Bolton says.

The census of 1820 counted 14,273 people (minus the Cherokee) in the territory. By 1830 there were 30,388.

"One of the most important things to becoming a territory ... the government has a responsibility. You're sort of a ward of the government, and the government starts spending money, which they did in Arkansas, and that made an important difference," Bolton says.

There was also a desire for land.

"More public land was sold in the 1830s, I think, than at any other time in American history," says Bolton. "It was $2 an acre, pretty much. People wanted new land."

By 1836, the territory, which had a western border after the Cherokee were forced out, was on the verge of becoming part of the Union.

Bolton writes of the debate that was stirred by the possibilities of statehood:

"A group of Jackson County petitioners for statehood made it plain that they had come 'from old and organized states' and wanted to be once again 'upon a footing of equality with our brethren from whom we have separated.' Statehood was simply another form of territorial ambition."

Style on 02/25/2019