One hundred years and one day ago, the Arkansas Legislature ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ensuring that no citizen can be denied the right to vote on the basis of sex. The Susan B. Anthony Amendment sailed through a special session convened by Gov. Charles Brough on July 28, 1919.

The vote was 29-2 in the Senate and 75-17 in the House.

That doesn't mean there was no opposition. And I wouldn't be too quick to declare the state's rapid ratification of Susan B. Anthony as some sort of finest hour. But let's see what you think, Friendly Reader.

Arkansas was the 12th state to ratify women's right to vote, which was remarked upon at the time, as was the apparently even more remarkable fact that Arkansas was the second former Confederate state to ratify, after Texas. Louisiana, Alabama and Georgia already had said no, and the rest of the old South also would say no — for a decade or more. Mississippi wouldn't come around until 1984.

So what were the antisuffrage reasons? That ugly politics might sully woman's virtue and that babes would be left unfed and dirty-toed while Mama traipsed to the polls? Yes, and we know this because the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat quoted everybody in sight. Also, they reported arguments made for the official record, out loud and on the floors of both legislative chambers.

In the state Senate, Sen. Houston Emory of Garland County proposed that, instead of mere men ratifying the 19th Amendment, the state's women should be asked whether they wanted the men to ratify it. He proposed waiting to do that during the general election of 1920.

He had it all figured out. White women could be given a separate ballot on which would be printed "For Suffrage" and "Against Suffrage." Election commissioners would keep separate poll books upon which would be recorded the names of the women voting on the question. Those women would only include all the white women who had been residents of the state for one year and of the county for six months and of the township or ward for one month and who were older than 21.

After Emory explained his plan in the fine language used for such things, Sen. J.S. Utley of Saline County rose on a point of order to ask the president of the session, Sen. Benjamin E. McFerrin, whether Emory's motion could be entertained legally when the session had been called specially to consider ratification. McFerrin ruled that no, it could not.

Next, Sen. Harry L. Ponder of Walnut Ridge paid high tribute to women for their work in the recent struggle for worldwide democracy and said they would have a good moral influence in elections.

Ponder was interrupted over and over by applause from the gallery, which was full of women.

Emory then asked for time to explain why he — such an ardent supporter of suffrage — wanted to let the women decide. He declared that the place for the women was at home, where they had more influence. "The hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world," he said.

Sen. W.L. Ward of Lee County spoke for 20 minutes against ratification. His arguments boiled down to this: "If this amendment is ratified by this legislature today, there will be a domination of the negro race in the South."

Sen. R.L. Collins of Drew County, who supported ratification, advised Ward not to fret: "We'll attend to the negro vote all right."

Ward asked him, "You say you will attend to the vote of the negro — well, how are you going to attend to the vote of the negro except through unfair tactics?"

"Well, there may be several ways," said Senator Collins. "I remember one time I was in charge of a ballot box in which there were 319 negroes' votes and only 17 white men's votes. I was riding mule-back. Just as I got about in the middle of the bridge while crossing a creek, my mule suddenly became frightened, pitched me off and I accidentally let the ballot box drop into the creek. Neither box nor the votes have been seen since."

Note here, Horrified Reader, that this was an argument in favor of allowing women to vote.

Sen. W.H. Latimer opposed ratification, saying intelligent women in his district would stay home and the unintelligent ones would vote.

Meanwhile, in the House, Rep. J.A. Choate of White County said he refused to impose suffrage upon women, because it would force white women to serve in juries with "negro wenches." He would rather double every man's poll tax and give him two votes because the women would vote with their husbands anyway.

Other senators said that was nonsense. Rep. Charles E. Sullenger of Mississippi County spoke for ratification, saying he had no patience with the "bugaboo of negro domination" because "the Anglo-Saxon" would take care of that: "The best friend the negro has is the white man of the South," said he, "but we insist that the negro shall stay in his place." By dropping his votes into the creek, of course.

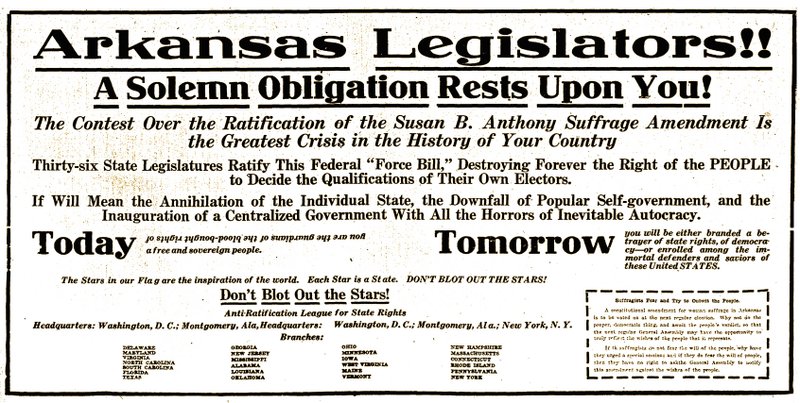

The Gazette reported that messages opposed to ratification also were read from out-of-state advocacy groups. These warned that the amendment was a "force bill" that would take away state's rights, that women didn't want to vote, that the haste to ratify was "unseemly" and partisan and related to the 1920 presidential election.

My favorite anti-suff was Miss Charlotte Rowe of Yonkers, N.Y., field secretary of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Unfortunately, the photo the Gazette published of her is too much like mud to bother reprinting. But contemporary images can be found by searching Newspapers.com for her name and the word “suffrage.” Look especially at the May 26, 1915, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, The Evening Public Ledger of April and May 1920, and The Brooklyn Citizen of Aug. 9 1920.

This willowy, witty, probably 35-year-old professional activist protested at length against being "thrust from the quietude of our homes into the contaminating atmosphere of political struggle."

Rowe declared that the 700,000 home-loving, quiet women she represented as well as a million even more quiet women "look with confidence to you, in whom the high traditions of the South still live, to protect us from this device of Northern abolitionists, which, if adopted, will, it seems to us, be not only debasing in its effects upon woman character, not only productive of discord in the sweet harmony of the family circle, but will inevitably result in striking down the barriers which you and your fathers have raised between Anglo-Saxon civilization and those who would mongrelize and corrupt it."

Men were enslaving themselves to a "petticoat government," she said. And suffragists were bad people. During the war they never praised the Army. Instead they used the Socialist and the coward slacker vote to win their cause.

The League of Women Voters was politically immoral, she said, being based on sex. And women voting would lead to a sex war, too. The Civil War had proved that votes sometimes needed to be enforced by guns. Were women going to back up their votes with guns? Were they going to ask men to do that for them?

"But suppose there aren't enough men to support the side for which the women have voted? You can imagine the confusion that will result."

I found more than 800 reports on Rowe's activism in various states between 1911 and 1920 by searching Newspapers.com. I've read her testimony before congressional committees. But her name isn't unique, and I haven't been able to follow her beyond the end of her fight against her right to vote.

Her lost cause heaped upon The Lost Cause, whatever did a charming, unmarried woman from Yonkers do with the rest of her life once thrust from the quietude of home into the contaminating atmosphere of political struggle?

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

Style on 07/29/2019