The pilots of the flight school at Eberts Field who began trying to make a living in the stunt business when the first world war ended were not the only aviators determined to stay aloft in 1919.

The "birdmen" envisioned peacetime applications for flight. They didn't want to give it up, no matter that it was a seriously risky occupation even without anybody trying to shoot them down.

They could deliver the mail. They could deliver cargo. They could deliver the newspaper. The Denver Post bought an airplane in June 1919 to deliver papers to suburbs.

And the public was thrilled by the spectacle of flying machines, so there were advertising applications. Crowds would turn out to watch a publicity stunt flight and scurry around picking up any marketing litter the pilots tossed down.

The word "aviators" appeared 343 times in the Arkansas Gazette in 1919 (in 17 of those instances, the next word was "killed"). Arkansans looked up, literally, to aviators in part because of commercial ventures by Eberts Field aviators, but also because aviators everywhere were blazing a trail of glory through the sky.

Flying clubs, newspapers and wealthy enthusiasts offered prizes to encourage distance records. The most heavily covered was the London Daily Mail's offer, dating from 1913, of $50,000 to the pilots of the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean — without stopping.

The prize inspired three big achievements in early 1919:

On March 19, the Arkansas Gazette reported that British pilot Harry Hawker and his navigator Commander Mackenzie Grieve had arrived from England at St. John's, Newfoundland, with a secretly built airplane that they intended to fly back to England.

The machine is a Sopwith two seater biplane, with a 375 horsepower engine. The fuselage is boat-shaped and will support the machine in the water.

They had shipped it across the Atlantic so their prize flight could take advantage of west-to-east prevailing winds.

Hawker predicted the flight would take 19½ hours. He said the plane was capable of flying 100 mph for 25 hours.

Other British teams arrived about the same time to try the same thing, but Hawker and Grieve made the biggest splash — as it were. After weeks of delay due to bad weather, they took off May 18 and managed to make it about halfway across before the water filter choked and they were forced to set down in mid-ocean.

For nearly a week Hawker and Grieve were believed lost, but they had been rescued. They turned up safe aboard a small craft and were almost to Ireland before news reached shore. A British destroyer sailed out to carry them in amid journalistic rejoicing.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy also had its eyes on the prize — though not quite the same prize.

Commander John H. Towers, who had been in charge of the Naval Reserve Flying Corps, was ordered in February to make a trans-Atlantic flight happen. A report in the Gazette reminded readers that, during the war, the Navy had developed a "monster seaplane" with three Liberty motors giving it about 1200 horsepower.

This machine has as its body a substantially built boat and has carried 51 persons in flights of considerable lengths. It has been within the last few weeks repeatedly tested out along the Atlantic coast with great success.

The Navy wasn't interested in crossing for the sake of crossing first, and it didn't build a plucky little fat-belly biplane for the task. Its goal was conveying submarine hunters overseas without having to pluck off their wings and pack them into a ship first. The "Monster" NC-4 and two sister seaplanes had machine guns.

Towers planned rest stops along the route the big birds would fly. The plan was to make "the hop" a 19-day series of hops. On May 8, three planes left Rockaway, N.Y., and touched down in Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and the Azores before continuing to Lisbon, Portugal, and from there to Spain. A chain of ships stationed along the route shone their lights to mark the way through the nights.

Two of the planes, NC-1 and NC-3 had to set down midocean because of dangerous fog. The NC-3, with Towers as pilot, taxied to the Azores and was towed home. The NC-1 was too damaged during the rough landing to restart; the crew were rescued, but the plane sank while being towed.

THE SIRS

Two weeks later, another team from England set out from Newfoundland.

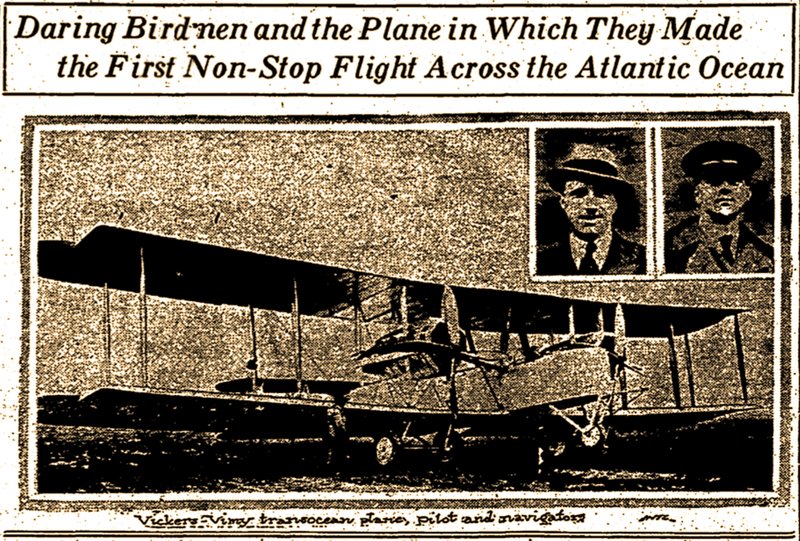

A two-line, banner headline in the Gazette reported the outcome: "Non-Stop Flight Across the Atlantic Achieved By English Pilot and American Navigator in 16 Hours."

Captain John Alcock and Lieut. Arthur W. Brown actually needed 16 hours and 12 minutes to fly their Vickers-Vimy twin-engine biplane to Clifden, Ireland. The Vimy, a warbird, carried extra fuel tanks where its bomb racks had been, and the engines were Rolls-Royce 360 hp. The cargo included sandwiches and coffee, a bottle of whiskey, a 4-pound sack of mail and two toy cats — "Lucky Jim" and "Twinkle Toes."

Other lucky charms on board were a small silk American flag in Brown’s wallet, a horseshoe under Alcock’s seat, a wee silver kewpie doll and little ragdolls named "Ran-tan-tan" and "Olivette."

The landing was made at 9:40 o'clock, British summer time. In taking the ground the machine struck heavily and the fuselage ploughed into the sand. Neither of the occupants was injured.

Much of the flight was made through a fog with occasional drizzle. They had worried supporters by not radioing back reports of their progress. Alcock explained that what the newspaper called "the wireless propeller" blew off soon after the airplane left Newfoundland.

Alcock planned to fly the plane the rest of the way to London, after repairs.

A few days later, the men met King George V at Windsor Castle, and he made them Knights Commanders of the Order of the British Empire.

Sir Arthur Brown went on to a career in commercial aviation and served in the Royal Air Force for a while during World War II — until his health declined and he had to retire. His son, an RAF pilot, crashed and was buried in the Netherlands in June 1944.

Brown's health worsened until he died of an accidental overdose in October 1948. He was 62.

Capt. Sir John Alcock crashed in a fog in December 1919, in France, and died in a hospital there. He was 27 years old.

Email:

cstorey@arkansasonline.com

Style on 06/10/2019