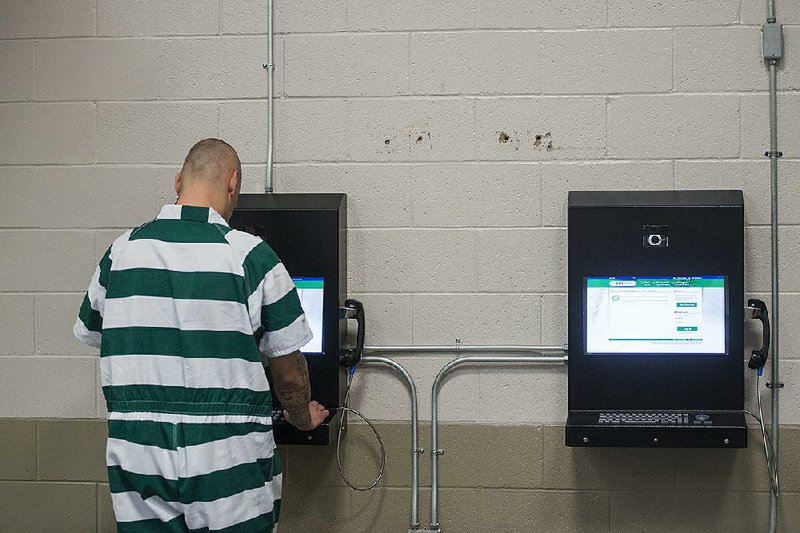

BENTONVILLE -- The Benton County sheriff's office did away with prisoners' in-person visits with loved ones last year. Instead, visits are conducted electronically, some through kiosks using equipment installed at the jail.

The system also allows someone to visit a detainee using a computer, smartphone or tablet through the website smartjailmail.com. The user must set up an account and log in to set up visitation times.

But some visitors and prisoners complain that the system doesn't always work.

Barbara Harris recently logged in using a kiosk at the jail to visit her son but couldn't connect. She went home without seeing him.

"It's sad what people have to go through," Harris said. "The families are also being punished, and they did not do anything wrong."

Each video visitation costs the user 50 cents per minute, and visits must last at least 15 minutes. That means the minimum cost for a video visitation is $7.50. The visits at the jail kiosk are free.

Prisoners are allowed two visits per week, just not in person. They can visit via kiosks in their jail pods. They can also use the machines to send email to friends and family members.

Sgt. Shannon Jenkins, a spokesman for the sheriff's office, said there was no cost to the sheriff's office for installing the kiosks and equipment. All of the proceeds go to Smart Communications, a Florida-based firm that installed and operates the system.

Jenkins said there may have been glitches with the system when the jail first switched to it last fall, but she hasn't received any complaints since then.

But Harris and others complain about not being able to connect to the system, or about lacking audio or video feeds when they do. Harris said she told workers at the jail's front desk about the technical problems.

Adam Flores, a prisoner earlier this year, sent an email saying inmates would prefer in-person visits over electronic ones.

Flores said technical issues sometimes prevented scheduled visits from happening. He had family members drive from Oklahoma to visit, but they had to leave without seeing him because they could not connect with him through the electronic system, he said.

He said he told deputies about the problems.

"I know I put myself here, but that doesn't mean punish our families," he said.

Jon Logan, chief executive officer of Smart Communications Systems of Apollo Beach, Fla., said he understood the frustration visitors feel when technical problems arise.

"No system you can make is going to be 100% reliable all the time," Logan said. "If local Internet goes out, we can't do anything about that. If you lose a connection at your home, we can't do anything about that either. We know when it happens, though, because we are monitoring the system all the time. If something goes wrong and we can fix it, we will."

"This is a fee-based system. If people aren't using it, we go out of business," he said.

The jail staff has turned in 13 maintenance tickets since the beginning of the year, and the company has sent out two technicians this year, once to replace a kiosk, he said. He added that the jail logs hundreds of visits each month.

Smart Communications contracts with 100 jails across the United States, Logan said.

Last year, the Washington County jail also switched to a video system. People can visit a Washington County detainee for free via a jail lobby kiosk up to two visits per week and can make phone calls for a fee.

Video visitation is in hundreds of jails and prisons across the country, said Wanda Bertram, a spokesman for the Prison Policy Initiative. Use of video visitation systems for jails and prisons began to grow five or six years ago, and it's common for jails to eliminate in-person visits after implementing video visitation, she said.

Bertram opposes jails eliminating all in-person visits, though. "It is more likely that people will return to jails without a solid family foundation," she said.

Jenkins said last year that video visitation would help reduce contraband getting into the jail. Fewer people at the lockup means there's a smaller chance of contraband getting through.

Video visitation also means less work and risk for deputies because inmates are no longer moved from their cells for in-person visitations, she said.

Ron Stanfill visited his son earlier this year in the jail. He said he's not a fan of the video visitation and would rather sit and talk with his son through a glass pane. He also doesn't like the quality of the video.

Harris said she prefers in-person visits so she can see her son face-to-face through the glass pane and can talk with him over the telephone.

At least one sheriff in the nation agrees with them. Sheriff Garry McFadden restored in-person visitations Jan. 16 at the Mecklenburg County lockup in Charlotte, N.C.

"Allowing our residents to stay connected to family and loved ones through in-person visits improves public safety," McFadden said.

"This simple step alone has been shown to significantly lower the chances that a person will commit another crime after they get out. It also reduces the chance a person will commit an infraction inside the jail, which could adversely impact their release. In addition, it improves mental health outcomes and strengthens family units and community ties," he said.

Metro on 06/10/2019