Arkansas' fastest-growing higher-education student population also goes to high school.

These students don't live in dormitories, have meal plans or maybe even go to the campus at all. They aren't eligible for financial aid under federal Title IV, either.

Yet, colleges and universities are increasingly reaching out to high schools and their students to capitalize on students' desires for cheaper college credits and their potential loyalty to the institutions that made the credits available to them.

The high school-based instruction, called "concurrent courses," has drawn criticism as not being rigorous enough and enrolling disproportionate numbers of white students with higher income levels.

Information analyzed by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette shows that when compared with high school and higher-education demographic data, white students are overrepresented among the state's concurrently enrolled students, while black and Hispanic students are underrepresented.

Little data exist to determine the value of concurrent courses to colleges, and few laws or regulations govern how the partnerships must work. Arkansas high schools and higher-education institutions collectively operate under hundreds of partnerships.

Governmental definitions across states and the federal government don't even match on concurrent enrollment and its cousin, dual enrollment. (In Arkansas, concurrent courses count for both high school and college credit. "Dually enrolled" students take courses counting only for college credit.)

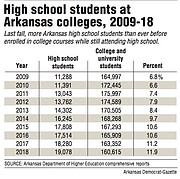

Despite the patchwork setup, the number of high school students enrolled in college is growing, and fast, according to Arkansas Department of Higher Education reports. About 7,500 high school students took college courses in the 2005-06 academic year. This year, more than 19,000 did.

It's a boon to the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope-Texarkana, even though high school students pay a discounted tuition, said Brian Berry, vice chancellor for finance and student services.

"They're coming into classes and they're filling seats that might otherwise go unsold," he said.

In recent years, the state Higher Education Department and lawmakers have added rules on concurrent enrollment to hold course teachers to minimum college faculty requirements, and to hold the courses to the same college and university curriculum requirements.

This year, the Arkansas Legislature passed Act 456 to offset tuition for high school juniors and seniors, under certain conditions.

Some school districts help students pay for concurrent courses and some don't, said Sen. James Sturch, R-Batesville, the act's sponsor.

"To me, that wasn't fair or equitable at all," he said.

COST AND EQUITY

The University of Arkansas Community College at Hope-Texarkana isn't like the other community colleges, at least not right now.

It's the only Arkansas school among 44 nationwide participating in a Pell grant pilot program for high school students.

Pell grants cover tuition and other costs of attending college up to about $6,000 per year for low-income students. The grants are restricted to students with high school diplomas or equivalency degrees.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Education temporarily waived that requirement at those 44 institutions.

The change covered 207 of the community college's concurrent students, and its concurrent enrollment grew by more than 100 students.

Cost has been a "huge issue," even with the discounted tuition, Berry said.

Colleges and universities typically reduce tuition for high school students. Sometimes school districts or philanthropic organizations cover the costs of tuition or books. Often, students and their families must pay.

The Pell grant pilot program is ongoing, and some people are skeptical about whether the program is the right way to expand financial aid.

Arkansas Department of Higher Education Director Maria Markham said Pell grants come with strings attached -- such as suspension for poor academic performance -- and a high school student may be too young to fully understand the consequences of signing up.

If the student takes courses in high school that they don't end up needing in college, she said, they may waste valuable Pell grant eligibility, which lasts 12 semesters, or six academic years.

"It puts a lot of responsibility on the high school student to think about their future," Markham said.

Better guidance from school counselors or college advisers for high schoolers would help them understand what college courses they need, Markham said. Right now, some students sign up for every college course with little thought of what they will need once they become undergraduates, she said.

Summer Pauley, a psychology and sociology major at Arkansas Tech University, said she didn't think all of the concurrent courses she took at the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope-Texarkana were necessary for her degree program, but they all transferred at least as electives.

Pauley arrived at Arkansas Tech from Hope High School with 51 concurrent credits -- more than three semesters -- all paid for by a Pell grant. If she graduates next spring as planned, she will have spent five semesters at Tech, not including a semester she took off to take part in the Disney College Program.

A Pell program helped Justin Brown, 19, take 15 credit hours while he was still at Lafayette County High School, which will help him spend two years at the Hope-Texarkana college taking extra prerequisites for nursing programs in the state.

"If I had to pay for those classes, it probably would have been difficult to even take those courses," he said.

Brown was born prematurely, and when he was 16 and 17, he spent his summers volunteering at the hospital that saved his life, Wadley Regional Medical Center in Texarkana, Texas. He had known for years that he wanted to go into medicine -- much earlier than most people pick out their careers. He's worked with his counselor to take only necessary courses.

The Arkansas Concurrent Challenge Scholarship, created by Act 456 of 2019, has no bearing on federal financial aid eligibility, Markham said.

The scholarship is third among Arkansas Lottery funding tiers. Money is available after funding has first been provided to the Academic Challenge Scholarship and then to the Workforce Challenge Scholarship. It's unclear how much money would be available.

The funds, up to $125 per course, are available only for two courses per semester to academically qualified high school juniors and seniors. Arkansas rules allow ninth- through 12th-graders to enroll in unlimited concurrent courses, but Sturch wanted to rein that in for the scholarship.

Juniors and seniors are more college ready and are thinking more about what they'll study if they go to college, he said. The scholarship requires a "student success plan" to prevent "willy-nilly choosing of classes," Sturch said.

"I didn't want to set anybody up for failure," he said. Sturch also wanted his bill to help standardize how the programs are run across the state.

Data on concurrent student income levels aren't available. Markham said the Higher Education Department may be able to measure that in the future.

In Oregon, federal researchers found that concurrent course participants were disproportionately white, female, high-achieving and above the income eligibility for the federal school lunch program.

The National Center for Education Statistics reported in February that high school students whose parents had higher education levels and students who were white or Asian more often enrolled in college courses.

White students, who make up about 62.1% of Arkansas high school populations, represented at least 72.1% of the students taking the concurrent college courses, according to 2018-19 data. The vast majority of concurrent students attend public institutions.

Black students, who make up about 19.8% of high school populations, comprise no more than 10% of concurrent students. Hispanics make up 12.7% of high school students but represent no more than 8.2% of concurrent students.

Bills like Sturch's offer some promise for poorer students, said Rep. Vivian Flowers, D-Pine Bluff, immediate past chairman of the Arkansas Legislative Black Caucus. But in Flowers' experience, equity-focused programs are more successful when they target diverse populations.

Sen. Joyce Elliott, D-Little Rock, the current caucus chairman, called for "intrusive outreach" to reach those students who may be the first in their families to attend college and are unaware of opportunities.

Rey Hernandez, state director of the League of United Latin American Citizens, said the disparity could be traced back to "too few teachers of color in school districts."

"So there is little representation or understanding of what the capabilities are for nonwhite students," he said.

The ACT score requirement of 19 for the Arkansas Scholarship Lottery can leave out minority-group students, too, Elliott said. Black and Hispanic students average scores below that, she said.

Colleges and universities, mostly private, across the country are moving away from using standardized test scores as admission criteria because of evidence that those scores pose an advantage for certain students, such as those who can afford preparation courses.

RIGOR OF SERVICES

Arkansas rules for the concurrent course program stipulate that students must have completed the eighth grade and have at least a score of 19 in reading on the ACT.

Schools set their own admission conditions for grade-point averages, ranging from 2.0 to 3.5 on 4.0 scales, and they can raise ACT score requirements.

General education courses taken at or from public colleges and universities are transferable to all other public institutions, by state law, but private institutions can be pickier about the course transfer credits they accept.

Concurrent courses are typically taught in two ways: On the college campus with other college students, or on the high school campus with certified teachers. Those teachers may be college instructors but are often high school teachers approved by the college to teach the course. Arkansas Tech offers courses online with the Virtual Arkansas program, but only within its 13 partner school districts.

To teach a nonvocational concurrent course at a high school, an instructor must have either a master's degree in that subject area or a master's degree alongside 18 credit hours in that subject area.

That's long been the standard in Arkansas and required at the National Association for Concurrent Enrollment Partnerships, an accrediting agency for more than 20 Arkansas colleges' concurrent programs.

When the Higher Learning Commission, the accreditor for Arkansas' public institutions and others across a 19-state region, added that standard in 2015, schools across the region couldn't meet it. The commission delayed the rule to 2022 for many colleges.

The commission is not planning to make more rules but is interested in seeing if more 10th-graders and below start getting more concurrent credits, spokesman Steve Kauffman said.

Many higher-education officials contend that high school instructors are not as qualified as college or university instructors (who often have master's degrees or above in the subject area), that many of the students taking concurrent courses aren't ready, or that the courses lack the uniform oversight and assessment of Advanced Placement courses.

Supporters of concurrent courses argue that new rules are standardizing the programs and that existing Arkansas policy requires textbooks, syllabuses and exams to be the same as the college course.

That doesn't mean a ninth- or 10th-grader is ready to take college history, Arkansas State University history professor Erik Gilbert said. Sophomores who take concurrent history or science courses may be unable to adequately build on that knowledge base once they get to college years later, he said. Some may have to repeat those courses.

In a 2017 Chronicle of Higher Education op-ed, Gilbert wrote that, because of concurrent enrollment, he now teaches fewer students in lower-level history courses, including honors history. One semester, three students enrolled in honors history. The ones who enroll miss out on the lively discussion that once filled the often overflowing classes, Gilbert told the Democrat-Gazette.

They also are more often from backgrounds that are less represented among concurrent course enrollees.

"The students in my [general education] classes are disproportionately minorities, adults, and graduates of rural high schools," Gilbert wrote in the Chronicle. "I am teaching fewer middle-class, suburban, white students. So what's happened? For middle-class students who attend well-funded high schools, general education at less- and moderately-selective state universities is increasingly a thing of the past."

Gilbert said the best solution "to level the playing field" is to eliminate concurrent courses and even Advanced Placement, although he said Advanced Placement is much more controlled and monitored by an outside agency. Or, colleges could eliminate general education requirements, as European institutions have done.

The University of Arkansas at Little Rock's Institutional Effectiveness Committee reported concern that concurrent accreditation is "not based on student learning outcomes, but rather processes."

Elliott, the state senator, said concurrent offerings have drifted from high school enrichment to competitive assets.

Many college leaders see themselves as providing a necessary product to Arkansas students.

"We see this as a service," said Blake Bedsole, vice president for enrollment management at Arkansas Tech University. "There's no financial benefit to Arkansas Tech to do this."

Arkansas Tech staff members occasionally drop by high schools to see if courses are being taught as instructed.

As he crafted his bill, Sturch said he heard criticism from lawmakers, and college and university presidents about the courses not being rigorous enough.

"It's not always the case," he said.

Arkansas higher-education leaders will help ensure that the courses are rigorous, Sturch said. They don't want anyone repeating a concurrent course once they go to college, he said.

THE FUTURE?

Soon, Markham said, the Higher Education Department will seek more data from colleges and universities so it can better measure participation (by race and income) and outcomes, such as whether students who participate are completing college faster, or whether students who take college courses on college campuses perform better as undergraduates than those who took college courses on their high school campuses from qualified high school teachers.

Markham also wants to know if those who took concurrent enrollment courses perform better in college because of their concurrent course work or because they are higher-achieving students who were more likely anyway to go to college than their peers.

As Arkansas awaits more robust outcome data, Markham believes it may end up, initially, outperforming other states because it's had stricter course requirements for longer.

But Markham doesn't think community colleges have been successful in using concurrent enrollment as a recruiting technique, based on national research.

Many of those colleges in Arkansas haven't measured whether it's benefiting them.

"It's hard to answer whether or not we are reaping the true benefits [that] I guess we are supposed to be looking at, which is: Do they enroll here after graduation?" said Erin Dail, director of academic partnerships at the University of Arkansas-Pulaski Technical College.

Pulaski Tech began offering the courses in 2015, Dail said, to fill in the gaps where some schools were not being served with concurrent opportunities.

The role played by four-year universities can be different, as most -- other than Arkansas Tech and Henderson State University -- enroll far fewer high school students than do two-year colleges.

Leaders at the University of Central Arkansas don't see the university's role as being like that of Pulaski Tech.

"Our priority here at UCA is not on expanding our concurrent program but just on ensuring the students who enroll in UCA concurrent courses are getting a legitimately high-quality experience and credits," said spokesman Amanda Hoelzeman, attributing the sentiment to UCA President Houston Davis.

The UALR committee recommended more investment in concurrent programs to attract four-year recruits or the elimination of the programs because they were competing well against other schools' programs.

Whether or not students are enrolling at Pulaski Tech after high school, it's clear that the college's enrollment decline has been mitigated by counting high school students, Dail said.

"It's been a growing area for us," she said.

How numbers were calculated

To calculate the racial representation among Arkansas’ concurrently enrolled high school students, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette estimated ranges using data that included blacked-out records of enrollment by race.

The newspaper obtained enrollment by race and grade data from the state Department of Education’s Statewide Information System Reports, as well as data on the identified race and ethnicity of concurrently enrolled students by school from the Department of Higher Education. The higher education department redacted amounts of fewer than 11 students in any category, citing privacy reasons under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

For the concurrent data, the newspaper calculated the highest possible and lowest possible numbers of students in a race category where data were withheld and the highest possible and lowest possible overall total concurrent enrollment figures. It then calculated highest possible and lowest possible racial percentages by dividing the race estimates by the overall enrollment estimates. It compared the results to the state’s race data for grades 9 through 12.

No matter the scenario, white students, who make up about 62.1% of Arkansas high school students, represented at least 72.1% of the concurrently enrolled high school students and possibly as much as 75.3%.

Black students, who make up about 19.8% of Ar

SundayMonday on 06/23/2019