The creators of this film were not interested in the truth. They never interviewed a single solitary soul who knew Michael except the two perjurers and their families.

-- statement from Michael Jackson's family about the two-part HBO documentary Leaving Neverland

For a lot of my lifetime, Michael Jackson was arguably the most famous person on the planet.

We were born in the same year. (A cluster of iconic pop stars, including Prince Rogers Nelson and Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone, were born in the Great Lakes region in 1958.) By the time we were 11, Michael Jackson was famous as the youngest member of the Jackson Five, who would have seven Top 10 singles in 1970 and 1971. By the time I was in high school, he'd had three solo hits.

I wasn't a fan back then. My crowd dismissed the Jackson Five as bubble gum. Secretly, I imagine we all liked the music (how could you not?) but it wasn't until I became an adult -- not long after the release of 1979's Off the Wall -- that I genuinely started to appreciate what could be characterized as his genius.

I became a fan when Jackson took control of his career, started working with Quincy Jones, and started performing his own material, and stayed one through the 1980s. There was crossover sublimity available in tracks like "Beat It" and "Billie Jean." Jackson was a master of rhythm and groove; his sometimes unintelligible lyrics were best taken as an emotive current, the whoops and wails of a shamanistic performer.

But anyone who cared to examine the artist could tell something was amiss. If Jackson was a mature artist at the onset of his solo career, like the Peter Pan with whom he famously identified, he never grew up. He was always a junior member -- as well as the prime star -- of the family group. Younger brother Randy never supplanted him as the cutest of the moppets, sister Janet made her own way as a sitcom regular. At the cusp of the 1980s, Jackson was a young man, seemingly as naive as he was famous. He seemed to consciously adopt the aura of an alien, to be an asexual and untouchable creature. An E.T.

It says something about our collective wishfulness that we could embrace such a synthetically sweet being. The Michael Jackson of Thriller and "We Are the World" was always a fantasy -- divorced from messy carnality, suspended in a chilly self-constructed image cocoon. In the decade of the AIDS plague, Jackson provided the safest sex of all, a vague, prepubescent tingle of mysterious longing.

Had Jackson possessed a different quality of talent -- if he had, say, David Bowie's canniness -- he might have positioned himself as an avant-garde artist, and his experiments in cosmetic self-abnegation might have passed for commentary on the intractable American problem or the commercially driven urge to perfect one's body and visage. But as it was, his well-documented transformation from natural man to Diana Ross manque was a real horror movie. Less reversible than Bowie's serial identities, they were driven more by some pathology or inner vacuum than by a showman's desire to provoke.

Bowie was role-playing. He shed his costumes as he went along and ended up all right -- a fascinating and ultimately generous artist who was able to survive the early zeitgeist-bending power of Ziggy and the Spiders.

Jackson's behavior, his childlike mien, the way he seemed to be slowly transforming himself through surgery, made it apparent even in the mid-1980s that the man was mad. And sad.

I know this because in 1987 I wrote a critical evaluation of Jackson's career up to that point. I called it "Loving the Alien," copping the title of the Bowie song because that was how I felt about Jackson, whose increasingly odd behavior seemed on the verge of eclipsing an especial musical intelligence. Jackson was strange, but his music was irresistible to anyone with ears -- he was an authentic king of pop, maybe the most marvelous song and dance act to emerge since the Beatles.

At the time Jackson seemed nothing less than a kind of anti-Elvis, the black kid who could revitalize American pop by obliterating racial boundaries -- an acceptable, purifying filter through which the raw and voodoo dark roux of black sound could be forced. With an assist from Kramer-strangling Eddie Van Halen, Jackson single-handedly ended MTV apartheid with "Beat It," opening up the network for black or, as they had it, "dance" artists -- and he seemed capable of transcending race in a way that prefigured the globalization of Michael Jordan, who at the time was certainly the other M.J.

Those Quincy Jones-produced albums from the '80s must be considered some of the finest American pop music ever made, as important and influential as Presley's Sun recordings. Hear those albums now and they sound better than they did then, like a dose of the real thing after a couple of decades of imitation funk rock.

Except they don't. Because for obvious reasons, Michael Jackson's music doesn't make us happy anymore.

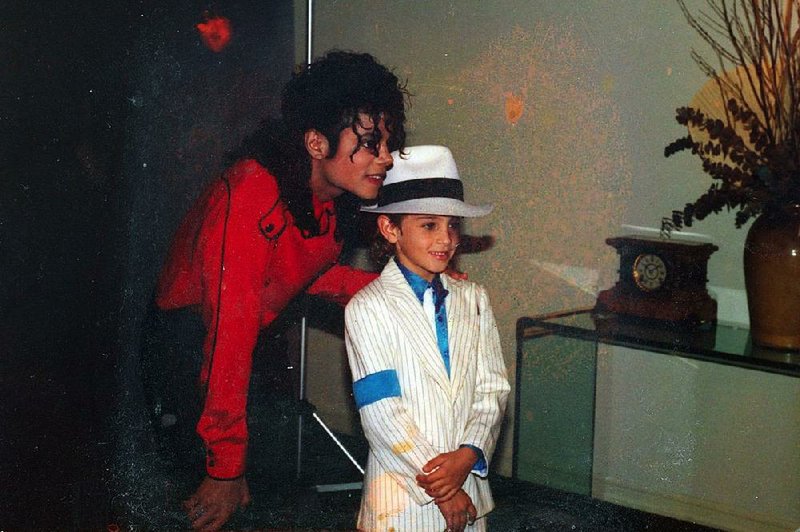

For the last 15 years of his life, Jackson was dogged by allegations of child sexual abuse. In 1994 he made an out-of-court settlement with the family of an alleged victim. From January 2004 until June 2005, Jackson stood trial on charges related to child molestation. He was acquitted by a jury. But if you paid attention to that trial, you might have taken into account how difficult it was to meet the state's burden of proof. You might have agreed that the jury did its duty, and still held grave doubts about Jackson's character and mental health and the advantages of deep pockets.

None of the revelations of Leaving Neverland surprises me.

I don't know if I should still enjoy Jackson's music, although I do. But I don't play it often, and I will probably play it less in the future, and when I do I will keep in mind that it is music made by a species of monster.

It is not unreasonable to see Jackson's affinity for prepubescent boys and his surgical experiments as attempts to escape himself. He never escaped the pop star trap -- when your work is essentially a juvenile form, the mere fact of getting older can render you ridiculous. He had the money to finance his attempt, to buy the silence of abettors and the assent of stooges. He made himself into a monster -- but he had help.

Other people have suffered lost childhoods and abusive parents and managed to be gentle and kind and honest in their dealing with others. I don't know Jackson's heart, but I can imagine it was broken. Just like the rest of him.

MovieStyle on 03/08/2019