VERDIGRE, Neb. -- Ice chunks the size of small cars ripped through barns and farmhouses. Calves were swept into freezing floodwaters, washing up dead along the banks of swollen rivers. Farm fields became lakes.

Such were the scenes the past week in Nebraska, Iowa and Wisconsin, which have declared states of emergency after the most powerful late-winter storm in a decade unleashed torrents of rain that melted snow, inundated rivers and topped levees.

The record flooding in the Midwest has taking a toll on farmers and ranchers at a time when they can least afford it, raising fears that this natural disaster will become a breaking point for farms weighed down by falling incomes, rising bankruptcies and the fallout from President Donald Trump's trade policies.

"When you're losing money to start with, how do you take on extra losses?" asked Clint Pischel, 23, of Niobrara, Neb., whose lowland fields were flooded by the ice-filled Niobrara River after a dam failed. He spent Monday gathering 30 dead calves from his family's ranch in this northern region of the state, finding their bodies under boulders of ice.

"There's no harder business to be in," Pischel added. "But with death and everything else, you've got to answer to bankers. It's not our choice."

Vice President Mike Pence surveyed flooded areas in Nebraska on Tuesday, where he viewed the raging Elkhorn River, talked to first responders and visited a shelter for displaced people. He promised expedited action on presidential disaster declarations for Iowa and Nebraska.

"We're going to make sure that federal resources are there for you," Pence told volunteers at Waterloo, a town of fewer than 1,000 residents about 21 miles west of Omaha that was all but cut off by the floodwaters.

The Nebraska Farm Bureau says farm and ranch losses in that state could reach $1 billion, and the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services warned that dirty floodwaters may have contaminated private wells.

Floodwaters washed away roads, making some communities unreachable in parts of the Midwest.

Flooding has closed more than 100 roads in Missouri. Seventy miles of Interstate 29 is closed from St. Joseph to the Iowa border, complicating efforts to access the Cooper Nuclear Station along the Missouri River in Nebraska.

A third of Offutt Air Force was underwater at one point as airmen raced around the clock to fill sandbags at the installation south of Omaha, where the military oversees nuclear deterrence and global strike capabilities. More than 3,000 feet of runway was submerged.

Airmen abandoned their efforts after the floodwater inundated buildings and hangars at the home of the U.S. Strategic Command.

"It was a lost cause. We gave up," said Tech. Sgt. Rachelle Blake, a 55th Wing spokesman, the Omaha World-Herald reported. No aircraft were damaged, and the command said it would ensure that its mission would continue uninterrupted.

Flooding also submerged a number of BNSF railway lines, with the railroad anticipating that tracks on its Hannibal and River subdivisions along the Mississippi River will possibly be out of service through today, according to its website. The Union Pacific railroad has also reported a number of rail lines out.

In February, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had to open the Bonnet Carre Spillway 28 miles upstream on the Mississippi from New Orleans to take flooding pressure off the city. The spillway, finished in 1931, has been opened only 13 times, and this is the first time it has been used in back-to-back years, said Matt Roe, spokesman for the Corps of Engineers New Orleans District.

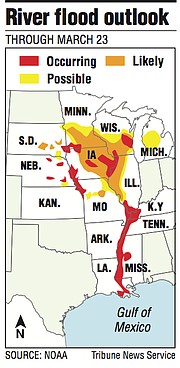

While floodwaters remain steady in some areas and recede in others, some regions are bracing for more flooding as rivers continue to crest this week, fed by rapid snowmelt throughout the Missouri and Mississippi River Basins, the National Weather Service said.

Nebraska was struck particularly hard. Of the four people killed in the flooding, three died in Nebraska. Two-thirds of the state's 94 counties and four tribal areas declared states of emergency. It was "the most extensive damage our state has ever experienced," Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts said Monday.

In Verdigre, the Ruzicka family has farmed for five generations, dating back to the homesteading days of the 1800s. The family's farmhouse is a total loss, a prized branding iron is missing and the family's first tractor, a 1930s model that was still used sometimes, now sits overturned in a pond of mud, its red wheels raised to the sky.

"There's not many farms left like this, and it's probably over for us too, now," said Anthony Ruzicka, whose alfalfa and corn fields were filled with giant ice chunks. "Financially, how do you recover from something like this?"

Last year, farms filing for Chapter 12 bankruptcy protection rose by 19 percent across the Midwest, the highest level in a decade, according to data compiled by the American Farm Bureau. Now, many of those farmers have lost their livestock and livelihoods.

The rail lines and roads that carry Midwest crops to market were washed away by the rain-gorged rivers that drowned small towns and forced thousands of people to evacuate. Some farmers say they have been cut off from their animals behind walls of water, while others cannot get to town for food and supplies for their livestock.

Farmers in the South are also bearing the brunt of the insistent rain and flooding, with many falling behind on planting corn, soybeans, cotton and other crops.

Some Midwest farmers were enlisted to use heavy equipment in recovery and rescue efforts, with at least one tragic outcome.

Working under the guidance of emergency crews in Columbus, Neb., James Wilke, a farmer in Platte County, was speeding in his tractor to help a person trapped in a car when a bridge collapsed.

"James and the tractor went down into the floodwater below," family friend Jodi Hefti wrote on Facebook.

In Holt County, Neb., Jerry Kohl, a rancher with 1,600 cows and 5,000 yearlings, lost dozens of cows over the past week, a loss in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Kohl, 60, said he had not slept for more than two hours at a time in nearly a week and had not tried to leave his ranch.

Farmers and ranchers also said they had lost miles of fences that pen in their livestock and hay bales that feed them.

Kohl said he had lost about 40 calves during the subzero cold and then the flooding.

Farmers said the losses are especially troubling because many cows give birth at this time of year, and the newborn calves arrived just as the blizzards started and floodwaters rose. Calves born under such conditions are at immediate and dire risk, Kohl said. If ranchers didn't get them to shelter within 10 minutes of being born, they probably didn't make it, he said. "And we had all those babies out there."

It is unclear when the waters will recede and reveal the full extent of devastation across the region.

A weak rain system is expected to move through the region over the next five days, according to Don Keeney, a meteorologist with Radiant Solutions in Gaithersburg, Md. "But amounts will be really light," Keeney said by telephone Tuesday. "It is not going to add to the flooding."

Information for this article was contributed by Mitch Smith, Jack Healy and Timothy Williams of The New York Times; by Alex Horton, Mark Berman and Reis Thebault of The Washington Post; by Brian K. Sullivan and Michael Hirtzer of Bloomberg News; and by The Associated Press.

A Section on 03/20/2019