On a recent March morning, the beautifully landscaped campus of the Beaver Water District headquarters is overrun with school-age kids, all darting to and fro while clutching sheets of paper in their hands. The morning holds a chill, but it doesn't deter the students, who are frantically trying to be the first to check off all of the items on the scavenger hunt-like lists in their hands. Inside the light-filled lobby area, more kids huddle around the model of the BWD's plant facilities, and a hum of young voices fills the space.

Just a typical day at the Beaver Water District, says retiring CEO Alan Fortenberry.

Through Others’ Eyes

“Dad is a very smart man and takes his job seriously and actually cares about what he is doing and is passionate about it. He enjoys his job and finds satisfaction in knowing that the BWD is producing and delivering a high quality product. Dad never just rushes into a situation without knowing all the facts. Dad is a planner and is always prepared for whatever task is at hand. He is very meticulous in his planning and preparation, so that he can develop the most appropriate plan of action for the best result. Dad is a very likeable guy, he is honest, trustworthy, dependable, caring and friendly.” — Josh Fortenberry

“If the founders of the Beaver Water District, Joe Steele, Clayton Little, Hardy Croxton, W.R. Vaughn, J. McRoy and Hal Douglas, had not had the vision to see the need for a long-term supply of clean, safe water for Northwest Arkansas 50 plus years ago, then the Northwest Arkansas we enjoy today would not exist. If Allen Fortenberry and his team had not had the vision to see the importance of educating our current population about the value of clean, affordable, abundant water, our most important natural resource could be being taken for granted. Remember that more than one half of the people living in Benton and Washington county were not born in Arkansas. So to them Beaver Lake has always been here and the question is there abundant, clean, affordable water has always been answered yes.” — Steve Clark

“He has very high expectations for his staff. He encourages them to set high standards for themselves. He provides a challenging yet rewarding workplace. He encourages multi-tasking and promotes networking.” — Stacy Cheevers

Next Week

Mike Poore

Little Rock

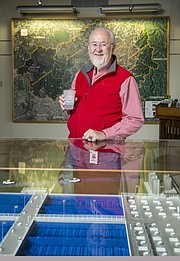

"We've developed an educational curriculum that teachers can use, and it's accredited by the State Board of Education," says Fortenberry with a note of pride in his voice as he drinks from a mug with "No water, no coffee" on its side. In Fortenberry's 28 years with the Beaver Water District -- serving as chief executive for 18 of them -- he's spearheaded a lot of successful initiatives, including the education outreach efforts. "These are sixth graders here today, I believe. If you can get them to understand the rain and where the rain goes, then you can get into a little bit deeper subjects. This is a K-12 program that we're doing today, but we go all the way up through adult education. Then we have a program for a much smaller group that we do annually for area leaders. With that, we go into pretty deep detail regarding the lake and Beaver Water District, what type of entity we are."

Fortenberry is scrupulous about passing on credit for many of his accomplishments over the years. He gives nods to the district's director of public affairs, Amy Wilson, and its education coordinator, Dot Neely, for their efforts in expanding the education program. The idea to emphasize education, Fortenberry says, came from former board member John Lewis. A quote by Lewis, who served on the board for more than three decades, graces the wall of the entry way to the main district building, reading: "Beaver Lake -- we need to preserve this great resource for future generations."

"It was his idea that, if you can educate children in regard to water and the importance of water and keeping it clean, it would be a generational thing," Fortenberry explains. "If you educate the children, number one, the parents will have to be educated themselves to answer the kids' questions. And, as that generation grows up, they're much smarter than we are in regard to water. And that's why we expend the resources to do that -- we feel it's very, very important."

Addressing young students on a regular basis has honed Fortenberry's ability to explain the purpose of the Beaver Water District in the most simple of terms.

"There was a little girl out there, she was kind of shy -- I saw her with some other girls, and she was the little one who wouldn't say anything and was just watching. We have a scale model of the plant out there, and I said, 'Would you like me to tell you how we clean the water up for you? The water you get out of your tap, at home in the kitchen?' And she said, 'Yes.' I said, 'When it gets to this big old tank here then we pump it to some tanks through some very big pipes, and then it goes to your house. We take all of the bad things out of the lake and clean the water up, and we deliver it to you.'"

Start 'em young

"For years, Alan has invited and educated the Fayetteville Chamber teen leadership classes and adult leadership classes at the offices of Beaver Water District," says Fayetteville Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Steve Clark. "So, we have had hundreds of identified Fayetteville leaders from the ages of 17 to 55 get a front row seat to the importance of water... [Alan] is the voice of science; he is the voice addressing current and future needs; and, finally, he is the voice reminding us all that water is the lifeblood of any community. All of this education is important because we must never forget that the amount of water for human use is finite, not infinite. Approximately 70 or 75 percent of the earth is covered by water, but only approximately 1 percent of that is available for human use."

If you want an example of how successful Fortenberry has been in his mission to educate future generations, just chat with his son, Josh.

"My dad always kept me up to date on what was going on at the Beaver Water District," he says. "Whenever there was an expansion or new construction project at the plant, he would explain why it was needed and how it would make the plant better. There were many times when Dad would take me to the plant and give me a tour while explaining each step in the water treatment process. He really enjoyed his job and would talk about the value of good clean water to the livelihood of Northwest Arkansas. I was always aware of why Beaver Water District existed, because Dad was very passionate about his job, and he knew how important it was to be able to provide affordable clean, safe drinking water to the people in Northwest Arkansas."

The result? Josh's career now follows in similar footsteps to his father's.

"While I am not an engineer like my dad, I did become very interested in water quality at an early age because of his influence," says Josh. "I went on to pursue environmental soil and water science at the University of Arkansas, and I currently work for the Natural Resources Conservation Service, focusing on land management to protect our natural resources. We have had numerous conversations about the many factors impacting water quality and the challenges that we face moving forward to maintain and improve the water quality of Beaver Lake and its tributaries."

Water and soil

Water and soil: Those are the two items that occupy Fortenberry's days and have, in fact, been a huge part of his life since he was born on a farm in northeastern Arkansas. He lost his mother when he was just 12 years old and grew up helping his father, who was a row crop farmer. When he landed at the University of Arkansas, he naturally migrated to a major in agricultural engineering. His high school sweetheart -- now his wife -- Patricia Rose had gone to college with him, and she moved to Little Rock to finish her degree in medical technology. Fortenberry followed immediately upon graduation, going to work for the Arkansas Soil and Water Conservation Commission.

"I was lucky to get that job and very lucky to have a great boss, John Saxon," says Fortenberry. "I worked for some great people and got a great, great education in Arkansas politics and Arkansas water issues and expanded my network."

The path that would eventually lead him to the Beaver Water District was, he says, pure "happenstance."

"You've trained yourself, you've created situations, but what you end up doing is more happenstance than it is by design," he says. "It's taking advantages of opportunities when they present themselves, and sometimes, that's just being in the right place at the right time, knowing somebody, finding out who is in your network."

Fortenberry had moved to Northwest Arkansas and to the private sector as a consultant when one of those matters of happenstance occurred: Richard Starr, engineering manager (the title would later be changed to CEO) of the Beaver Water District, invited him to lunch.

"I took him up on the offer -- a free meal," say Fortenberry with a chuckle. "Usually, it was the consultant buying the lunch for the client. So I figured something was up."

Starr recruited him for a position as an engineer at the district. He served in that position for 10 years, spending nearly half of that time overseeing a major expansion -- the building of a second water treatment plant. When Starr retired, Fortenberry was appointed as his replacement.

"I never dreamed, when I was picking cotton [as a child], that I would be what I am, in regard to this position," he says. "Even at college, I'd never dreamed of this. Even when I was consulting. "

And though the path may have started with happenstance, it ended with Fortenberry finding his passion.

"A lot of that [passion] came from the mentoring that John [Lewis] gave," he notes. "John continually encouraged me to look out, to envision -- he would say, 'What is this place going to look like in five years?' And then, after you kind of frame that in your mind, he would say, 'OK, what about 25 years?' And that's an intriguing exercise.

"I grew up in the time of wrist radios, Dick Tracy and Buck Rogers and that sort of thing, that was science fiction. And it's reality now. So I don't know if you can absolutely envision it, and it might not turn out how you would envision it, but if you have a passion for something, and you want to make it better, then you start dreaming about ways to make it better."

Educating the folks who get their water from the Beaver Water District was a goal for Fortenberry from the beginning of his tenure, which has coincided with the rise of the internet, making it easier for people to access information about their drinking water online. Unfortunately, says Fortenberry, that information is not always accurate.

"Utilities used to take the philosophy that they would rather fly under the radar, so it's been a tremendous challenge for us," he says. "That's what the kids being out here and adults coming out and the Citizens Water Academy is all about. That's just tremendously important for our business. And if you do fly under the radar, then we don't have these conversations -- and you would think that people would want to know what they're drinking. So we started bragging on ourselves -- we want people to know about the Beaver Water District. We want them to know what we do and how we do it. We want them to understand it, so they'll trust us.

"You can go on the internet, you can Google any subject, and you will get information -- but that doesn't guarantee the information is good. We want people to trust us to look out for their welfare. We're protecting your health when it comes to drinking the water, even though [it's] probably less than 1 percent [that] you're actually going to consume. We have to treat every drop. Even if it's going to wash turkeys -- they use 2.2 million gallons of water a day down at the Cargill plant in north Springdale. And those birds don't care what it smells like, tastes like. We would like folks to trust us that we know what we're doing in regard to their health."

Clearing the water

Fortenberry has taken great pains to communicate his message of potable water safety to Northwest Arkansas residents who might have immigrated from countries where water and sanitation issues are more fraught with potential danger than they are here. For example, the Beaver Water District has worked with Al "Papa Rap" Lopez, a Springdale activist who helps bridge communication with the Hispanic population in Northwest Arkansas. Also under his tenure, the staff of the district has grown, additional projects have been completed, and the district has expanded its affiliations with national organizations like the American Water Works Association, allowing local engineers to share best practices with other water districts across the country.

Not content to improve communication between the district and the general public, Fortenberry has made sure that the message of open communication lines is present within the organization, as well.

"I invite questions from the staff," he says, adding that the employees of the district "have a deep commitment to producing good drinking water. I've held monthly meetings with five or six people at a time, and those keep rolling. I tell them, 'Ask any question you want to ask me.'"

"The Q and A sessions serve to provide transparency," notes plant manager Stacy Cheevers. "This has been an opportunity for Alan, in his plan for succession, to share with the staff stories of history and to share why our policies and practices are important."

For nearly three decades, Fortenberry's focus has been on providing Northwest Arkansas with healthy water. But, he says, he knew the signs of change when they started popping up. It was time for him to turn over the reins so that someone else could champion the cause.

"I'm just wearing out," he confesses. "The travel, the responsibility, the decisions, the stress. ... I have pretty much exhausted my ideas. Somebody else with new vision needs to take it on. We're in good financial shape, we're in good staffing shape, we've got some excellent, excellent people working here. Very dedicated people. So from those standpoints, the district is in good shape."

Ask Cheevers what is Fortenberry's legacy for the Beaver Water District, and he has a ready answer.

"Modernization -- use of technology. Branding the district, to make the district known in our industry. Pushing us to the forefront to make us known -- public relations. Probably one of the biggest is the development of the watershed protection plan and the funding of such plan through work with the Northwest Arkansas Council."

"First, know that I believe Alan Fortenberry has done more than a first-rate job leading Beaver Water District," says Clark. "Through his efforts and leadership abundant, affordable, clean water has never been an issue when discussing growth and/or economic development in Northwest Arkansas. That is not the case in many areas of our country and not the case in every section of Arkansas. A report in 2010, almost a decade ago, indicated up to 24 Arkansas counties, primarily in the eastern part of our state, are considered to be 'extremely at risk' of a water shortage by or before the year 2050. When there is talk of a water shortage, there is very little talk of growth or economic development. Water is the lifeblood of any community or region. Alan knows that and lives it. That is why he is so persuasive when talking with others about the importance of water."

Moving on

In the end, says Fortenberry, it's the people that he will miss the most. He doesn't anticipate missing the daily grind. He hopes to increase the time he gives to his church, Johnson Church of Christ -- where, says friend and fellow church member Charles Couch, he's already pretty active.

"He's one of the elders at the church, and he takes an active role in his job," says Couch. He teaches classes on Sunday morning and on Wednesday night. He's an excellent teacher. It will be great to have him spend more time at the church."

Also on the retirement agenda: spending more time with his wife.

"I look forward to my wife and I working in the garden, pruning the roses when we should be pruning them, mowing when I should be mowing," he says with a smile. "I don't have any grand plans."

But it's unlikely that retirement will stop Fortenberry from proselytizing on his favorite subject. The lifelong student of soil and water remains in awe of the marvels that are Beaver Lake and the Beaver Water District. Much of Northwest Arkansas, says Fortenberry, doesn't realize what a gift the lake and the water that comes from it is.

"I've tried to convey [in my small group sessions], for the past year or so, the story," he says. "That's one of the things that's tremendously important, as I walk out the door. 'How did Beaver Lake get here? Why did Beaver Lake get here? What did it take for Beaver Lake to get here?' That story needs to be told, again and again."

The dry facts are: Beaver Lake was created by the Army Corps of Engineers during the first half of the 1960s by building a dam on the White River. The human aspects of the story, the feats that had to be accomplished in order to make it a success, go far beyond that, says Fortenberry.

"The vision that it took, the luck that it took, the design of how they went about even getting the lake built in the first place, and the things that fell in place -- and if that lake wasn't out there, we wouldn't be selling water to 350,000 people. There wouldn't be the large processing plants down here in the northern part of Springdale. I don't know if Walmart's corporate office would be here or not. I don't know if J.B. Hunt would still be hauling rice or not. Poultry couldn't have developed. The university couldn't have the student population that it has. The lake was the first regional effort up here. It wasn't XNA, it wasn't the interstate -- there would be no need for the interstate had you not had this project.

"Some of it was luck, yes, but it had to be put together really well. And then they had to pass federal and state law in order to pull this off. Throughout the history of Beaver Lake, there has been a tremendous effort from tremendous people to pull this thing together."

NAN Profiles on 03/31/2019