Most of the time at film festivals, I try to stick to a steady diet of movie screenings, and keep the other special events and parties to a bare minimum. But every year, by dint of their location in Manhattan and their patron saint and co-founder Robert De Niro, Tribeca's special showcases are indeed noteworthy, and this year, in particular, was an absolute deluge of high-caliber possibilities, including a screening/discussion of one of the funniest films ever made; a conversation between a towering colossus of modern cinema and one of his muses; and a world-premiere screening of a new cut of one of the major achievements of '70s-era American cinema, offering a post-screening discussion with the film's now-80-year-old director as an enormous bonus.

These possibilities, I could not pass up. So I forswore my normal working methodologies to attend them, each held at New York's ornate Beacon Theatre on the upper west side of Manhattan. Here's what happened.

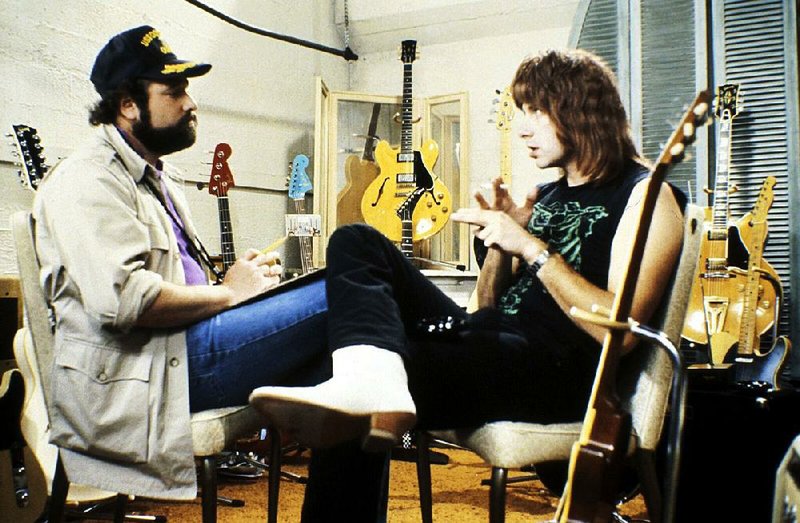

This Is Spinal Tap: 35th Anniversary

Writer/director Rob Reiner, and stars Michael McKean, Christopher Guest and Harry Shearer were on hand for both a post-screening discussion, and an abridged acoustic concert by the erstwhile Tappers.

The Beacon Theatre, around since 1929, is an ornate wonder: Three tiers of seats, with fancy, neo-Grecian plumage and elaborate, colorful decoupage covering the walls and ceiling. In keeping with its gold-leafed sumptuousness, the former first-run movie theater has housed some of the biggest and most venerated musical acts in entertainment.

So it's precisely the kind of place you would expect to see a fake, legendary band whose biggest hits include "Hell Hole," "Clam Caravan," and "Sex Farm." Spinal Tap, the gloriously fictitious group, whose story of managerial miscreancy and spontaneously combusting drummers is so beautifully memorialized in Rob Reiner's 1984 classic fake documentary (yes, before the term "mockumentary" was even utilized), began as a total gag only to actually tour with actual live dates in response to the film's cultlike following.

In the film, Reiner plays Marti DiBergi, the straight man director of the documentary, which follows Tap on a late-career U.S. tour in support of their newest album, Smell the Glove (the cover of which is so offensive to the label, that they instead release it in a totally black, blank sleeve, prompting the two best friend frontmen, David St. Hubbins (McKean), and Nigel Tufnel (Guest) to muse: "It's such a fine line between stupid ... and clever" -- Reiner's favorite line from the entire film).

By now, of course, Tap has long since been entered into the lexicon of pop culture lore (indeed, the ribald audience laughed uproariously in anticipation, before some of the film's signature moments even happened). Reiner's creation, mostly improvised by the killer cast, was wildly misunderstood upon its initial release: The director recounted a particularly painful test-screening in Dallas in which audience members came up to him to say "'Why would you make a movie about a band that nobody ever heard of? And one that's so bad?'"

After the screening, and an uproarious, unmoderated Q&A, the band got to the business of rocking out -- at least, acoustically speaking. Among their set, they included the aforementioned "hits' package, but also some other winks to the assembled throngs of superfans -- "Listen to the Flower People," a pre-metal Tap tune from the mid-'60s, designed to pander to the hippie set; and a riotous version of "Gimme Some Money" with none other than Elvis Costello backing them ("He still dresses better than us!" McKean announced).

Robert De Niro talks with Martin Scorsese

On the eve of the release of their ninth collaboration, The Irishman, celebrated director Scorsese met with the primary muse of his first three decades of work, De Niro, as the two talked about their projects working together, and some of Scorsese's work on his own.

It turns out that Bobby De Niro has at least one limitation. Easily one of the most celebrated actors of his generation, with a pair of Oscars, and an oeuvre that includes some of the best American films of the 20th century, Mr. De Niro, who also serves as one of Tribeca's original founders, didn't appear entirely comfortable on the other side of the microphone.

The pair, good friends since the '60s, offered an easy banter from time to time, but De Niro too often was guilty of staring at his notes and not actually listening to what his longtime director was saying (more than once, Scorsese would elaborate on an interesting point only to be met with an awkward silence before De Niro eventually stammered out a vaguely affirmative "Uh-huh").

Still, viewing a variety of clips from Scorsese's career (including King of Comedy, Casino, The Wolf of Wall Street, and Silence), it slowly became clear on project after project, that De Niro often provided his friend with a key service: pushing him to make the films in the first place. It was De Niro who got Scorsese to make Raging Bull, often considered a masterpiece, and likewise for The King of Comedy, as well as their forthcoming Netflix-released Irishman.

In describing his technique, Scorsese was at once passionate and articulate: Of his penchant for overhead shots, the director explained it wasn't intended to be a Godlike perspective, but rather the one he himself had, looking out forlornly from his apartment window as a young, somewhat sickly boy in New York's Lower East Side: "It looks great from up there."

Their best exchange came when, after a fight scene from Raging Bull, Scorsese described how he, a complete boxing neophyte (his term: "boring"), came to so memorably shoot those fight sequences. The key was to keep them subjective, from fighter Jake LaMotta's viewpoint, showing only those things he could see himself in the ring, and putting the audience in the middle of everything.

One point both of them could agree on was the talent of Scorsese's more recent leading man, Leo DiCaprio. De Niro recounted how he contacted Scorsese from the set of This Boy's Life, DiCaprio's debut feature, suggesting the director should try and work with him sometime. Since then, Leo has made five films with Scorsese, with two more in the works. "He's a really good kid," said De Niro, with Scorsese then calling out into the audience for Leo, who reluctantly raised his hand and stood up to thunderous applause.

Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut

In the film's 40th anniversary year, Francis Ford Coppola has released another cut of the movie that famously was one of the more difficult productions in modern cinema. After the screening, the director sat down with fellow filmmaker Steven Soderbergh to discuss the film, from its difficult production issues, and working with a famously unprepared Marlon Brando, to this new version of the Vietnam War classic.

Francis Ford Coppola had a run in the '70s unlike any other director in history: In 1972, he made The Godfather, long believed by many to be the best American movie ever made, which won the best picture Oscar; in April 1974, he released The Conversation, a classic paranoia thriller starring Gene Hackman that was nominated for best picture, but lost out to Coppola's The Godfather: Part II, released in December of that same year, which went on to also win five other Academy Awards, including best director. Then, in 1979, he released Apocalypse Now -- a film so difficult to make it gave his leading man a heart attack, and nearly lead to Coppola's total financial collapse -- which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes.

As with many brilliant artists, he sometimes hasn't known how to leave well enough alone. As absolutely fantastic as the theatrical cut of Apocalypse was (at 147 minutes), his turgid Redux (196 minutes), released in 2001, felt bloated and meandering, by his own admission, "too long." The newest version, he dubs optimistically The Final Cut (183 minutes), melds the two existing versions into something a good deal more cohesive than his earlier attempt at expansion.

He regrettably does include the nonsensical scene of otherwise grim and brooding Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), joyously stealing the beloved surfboard of the fiercely intense Lt. Col. Kilgore (Robert Duvall, who is absolutely indelible in the role), and giggling about it like a naughty teen; but the other added footage, mostly concerning a French plantation the bedraggled crew meet shortly after a deadly attack, has been sagely trimmed and shaped. So, while still didactic, it works much better in the flow of things than the previous version.

To my eye, the sequences with Col. Kurtz (Marlon Brando, of whom Coppola said "was a wonderful man") have mostly been retained from the original, which keeps the central mystique around the Colonel intact. Coppola, now 80, speaks lovingly of this film, which very nearly derailed his career (see his wife, Eleanor's, doc about the production, Hearts of Darkness, to find out why), and now, 40 years later, it's clear that all his pain and suffering weren't for naught. Of the misery of the shoot itself, Coppola is nothing but philosophical: "Extraordinary things happen to you," he says, "and it's up to you to make it positive because in this there is no hell, this is heaven, so make it be heaven. It's up to you."

MovieStyle on 05/10/2019