Earth has gone through some changes over the last billion years, give or take a million. Over the last couple centuries, artists have tried to capture those changes in nature. And the work of some of those artists is on display in Bentonville.

It's no small secret that Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art is a treasure for the state. And this weekend, Nature's Nation: American Art and Environment opens to the public. It'll remain there until Sept. 9. That'll give Arkansans and everyone else plenty of time to make the drive up Interstate 49.

At the start of the exhibit tour we were greeted by co-curators Karl Kusserow, the John Wilmerding Curator of American Art at the Princeton University of Art Museum, and Alan Braddock, Ralph H. Wark Associate Professor of Art History and American Studies at William & Mary.

These men with the impressive credentials know exactly what they are talking about with each and every piece they introduce. But the best part is how they relay that information with passion and enthusiasm in an understandable way to us folk without art degrees.

Mr. Kusserow wasted no time in setting the stage. The exhibit contains 300 years of American art showing how nature is represented, along with ecocriticism. That's the central idea in the exhibit: artwork that helped invent "ecological consciousness," according to Mr. Braddock. What visitors see is essentially a combination of science and art.

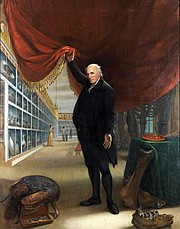

At the front of the exhibit stands a large painting titled The Artist in His Museum. It is a self-portrait of Charles Willson Peale, artist, scientist and founder of the Philadelphia Museum. Who better to introduce such a combination of science and art? Before ecology had officially been coined as a scientific term, Mr. Peale was using science and imagination to recognize man's impact on nature and tackle future environmental challenges.

Not far from Mr. Peale's portrait is a Native American robe woven some time ago in the Pacific Northwest that features a killer whale design. It was made around the same time as Mr. Peale's portrait and shows Native Americans' vision of order in nature.

People like Charles Willson Peale and the artist who designed the whale garment are visionaries, capable of seeing what would become ecology before the study's invention and from opposite sides of the country and different cultures. That's truly an amazing realization to share.

One of the displays that caught our eye came not long after Mr. Peale's portrait: three paintings from three artists, each of the extinct Carolina parakeet. Mr. Braddock uses them to illustrate how scientific attitudes began to change around the early 1800s as scientists started to recognize extinction could and was happening. Prior to that, he said, the common belief was that species couldn't disappear after first being created by a divine source. The mindset was that Earth existed in a mostly unchanging state. We know today that isn't the case. See: Ivory-billed woodpecker.

The Carolina parakeet became extinct due to hunters, farmers and loss of habitat. And the extinction contributed to the a change in mankind: For the first time, we realized as a species that we could change environments with our habits. Scientists and artists began to ask what responsibility Homo supposed sapiens had to prevent extinction, and that prevailing thought echoes throughout the exhibit.

Mr. Braddock introduces us to paintings by Homer Dodge Martin that epitomize the slow realization that humans can change Earth. Pieces like The Iron Mine, Port Henry, New York show how barren a mountain can look after being mined. There are also pieces that show a negative impact on the land as petroleum was discovered in West Virginia and began to spread as an industry. It's a startling thing to imagine how different certain areas of the world once looked, mind-boggling to imagine being there when these great innovations in technology are discovered and then watch as the land slowly responds to harvesting.

There are pieces detailing everything from the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to the nuclear bombs of World War II. Each reveal how the scale of mankind's effects on the world were increasing.

Our favorite piece looks toward the future: The artist is Alexis Rockman, and his painting shows mutated birds perched on a metal tree. It ponders what could be a bleak future where man's meddling in nature causes these birds to change, and the only habitat left for them is an artificial nature made by man. Mr. Braddock said the artist consulted with evolutionary scientists to get a picture of how the animals might look in the future.

It's difficult to walk through Nature's Nation and not feel aware of how man has changed the planet. Sometimes for the good; often enough, however, for the bad.

Isn't that what art is supposed to make us do? Think? Ponder our existence in the universe and how to better shape our immediate surroundings through changes? The change doesn't have to be dramatic. It can be incremental. We're thinking of getting some of those cloth grocery bags. That should make the sea turtles happy at least.

Editorial on 05/25/2019