As federal prosecutors see it, a series of $7,500 payments to former Arkansas Sen. Jeremy Hutchinson in 2013 and 2014 constituted bribery.

Hutchinson family members and supporters have argued that those checks and others like them were lawful compensation for services performed by the Little Rock lawyer outside of his legislative duties.

The payments by former executives of Preferred Family Healthcare Inc. of Springfield, Mo., totaled $60,000 over one seven-month period, according to a federal indictment in U.S. District Court in western Missouri.

Prosecutors say Hutchinson deposited the money before he filed an amendment to Arkansas House Bill 1129 that appeared to benefit the Missouri nonprofit, which supplied mental and behavioral health services to Arkansas Medicaid patients.

When the House bill became law in mid-March 2014, a former Preferred Family executive sent an exuberant email to other managers, court records show.

"Now we can breathe and live to fight another day! It's over!" the executive and Arkansas Capitol lobbyist Milton "Rusty" Cranford wrote. "Thank you Senator Jeremy Hutchinson and all! It[']s a great day!"

How Arkansas legislators might or might not profit from their public service is a sensitive subject around the Capitol these days.

After a string of federal political corruption investigations in the past three years targeted a half-dozen former state legislators, the Senate in recent months has adopted new ethics rules and the Legislature has embraced new ethics-related laws.

One focus has been a relatively unregulated practice in Arkansas politics: payments by lobbyists and their companies to lawmakers' businesses, including their law and consulting firms, as well as nonprofits, including churches.

In the past, ethics rules required state senators generally to disclose "any compensation he or she may have" related to a legislative proposal before lobbying or voting in committee or on the Senate floor. But the requirement was vague.

Additions last year to Rule 24.07 of the "Senate Code of Ethics" now specify that legislators who are business owners, lawyers, consultants or church and nonprofit executives must disclose by Jan. 31 each year clients and income through their businesses "derived from a registered lobbyist, or an individual or entity that employs a registered lobbyist."

The ethics rules were adopted last year, before Hutchinson's bribery conspiracy indictment was made public April 11 in federal court in Springfield, Mo. He's charged alongside former Preferred Family Healthcare top executives Tom and Bontiea Goss. Charges include conspiracy, fraud and federal funds theft and bribery.

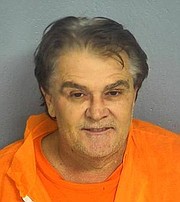

Hutchinson, nephew of Gov. Asa Hutchinson, and the Gosses have pleaded innocent and await trial.

Their indictment includes six pages detailing the making of Arkansas House Bill 1129 of 2014.

Citing emails, bank deposits and other records, that section of the indictment charges that payments to the lawmaker's legal work were tied to efforts by Preferred Family executives to influence Arkansas laws and regulations.

A guilty plea last year by another former legislator, state Rep. Henry "Hank" Wilkins IV, D-Pine Bluff, included charges that he accepted bribes through his place of work.

Wilkins admitted receiving more than $80,000 from former executives of Preferred Family Healthcare and others in exchange for legislative favors. Payments were disguised as contributions to the Pine Bluff church where he was pastor, St. James United Methodist, the plea agreement shows.

'ON A MISSION'

House Bill 1129 was a seemingly routine appropriations bill to help fund the state's Department of Human Services, which regulates Medicaid programs, health departments, nursing homes and more.

Then came Jeremy Hutchinson's amendment to the bill, filed in February 2014. Federal prosecutors say it was written by former Preferred Family Healthcare executives, whose company was then named Alternative Opportunities Inc.

The amendment aimed to postpone or kill three new initiatives by state regulators to contain costs for Medicaid services and measure how well the Missouri nonprofit and other service providers did their jobs.

During that time, Preferred Family paid Hutchinson a monthly retainer "purportedly as the Charity's attorney" even though he "often performed little, to no, legal work," the indictment charges.

Federal prosecutors say this is how the plan unfolded:

In April 2013, Cranford emailed other former Preferred Family executives that he had contacted Hutchinson and Wilkins to discuss three legislative proposals that would affect Medicaid service providers. All were measures proposed by the Department of Human Services.

"I have been on a mission with our Favorite (2) Legislators," Cranford wrote to Bontiea Goss, who served as Preferred Family's chief operating officer. "They jumped on the mission."

On May 30, 2013, Cranford told Goss: "we have Jeremy issuing a freeze in every committee of any Medicaid proposal."

She responded: "Jeremy rocks."

On June 10, 2013, Hutchinson deposited into a Bank of America account $7,500 received from a subsidiary of Preferred Family, Dayspring Services of Arkansas, the indictment alleges.

About two weeks later, Cranford emailed Jeremy Hutchinson with talking points to use in lobbying against one of the state's proposed cost-containment measures, "Episodes of Care."

Between June 10, 2013, and Jan. 7, 2014, Hutchinson deposited seven additional $7,500 payments from Preferred Family's Dayspring into bank accounts at Bank of America and Arvest Bank, the federal indictment says.

On Jan. 17, 2014, Cranford emailed Hutchinson an attachment, saying "Here is the bill." It aimed to suspend or stop all three regulatory efforts that Preferred Family opposed, according to the indictment.

The next month, Cranford emailed Hutchinson a new version, saying "it covers us for everything." Legislative records indicate that Hutchinson sent the draft to the Arkansas Bureau of Legislative Research, which writes proposed laws for lawmakers.

Cranford asked Hutchinson for daily progress updates: "Don't forget we need this each day [please]," according to the indictment. He also praised: "We know you are working hard on the bill. I have kept Bontiea in the loop every step of the way."

Then in mid-February 2014, a top administrator with the Human Services Department approached state Sen. Jonathan Dismang, R-Beebe.

The administrator asked for Dismang's help to revise the Hutchinson amendment to make it less problematic for the department's planned initiatives, Dismang said in an interview. Dismang is identified in the Hutchinson indictment as "Senator F."

At the time, Dismang told the Democrat-Gazette: "I didn't know Jeremy was working for" Preferred Family.

Dismang helped state regulators draft a revised amendment that was more favorable to the human services agency.

But the Hutchinson indictment said the revised bill still contained provisions "that were desired by" Preferred Family related to the three initiatives its executives opposed -- "Episodes of Care," "Health Homes" and "Youth Outcome Questionnaire."

Dismang said he believes his efforts succeeded in helping the state agency with the bill. The Hutchinson-Goss indictment doesn't accuse him of wrongdoing, and he says he is not under federal investigation.

Amendment 1, the revised Hutchinson amendment with Dismang's name listed as sponsor, was adopted by the Joint Budget Committee and became part of House Bill 1129.

Hutchinson and Wilkins voted in favor of the bill as it passed in the state House and Senate, the federal indictment against Hutchinson notes.

Not knowing then about Preferred Family's reported payments to Hutchinson, the political fight between the Human Services Department and the Missouri nonprofit didn't stand out as unusual, Dismang said.

"Service providers often had concerns," he said. "I wouldn't have seen what was happening as something extraordinary."

'CULTURE OF GREED'

Today's Arkansas Senate ethics rules likely would have required Hutchinson to submit a disclosure form showing his income as an attorney or consultant for Preferred Family Healthcare.

Legislators can report violations to the Senate Ethics Committee. Senators can hold hearings and levy penalties that range from a letter of caution to expulsion.

However, the Arkansas Senate ethics rules apply only to that chamber's 35 members.

The rules aren't a factor in the 100-member Arkansas House.

A pastor like Wilkins still wouldn't have to report contributions to his church of $1,000 or more from lobbyists or their employers, as he admitted accepting in his guilty plea.

House Speaker Matthew Shepherd, R-El Dorado, didn't respond to questions, but said this through a spokesman: "I have and will continue to consider what improvement may be required of House Rules. However, it is important that whatever we implement address an issue and provide clarity both to the members and the public."

Shepherd and Arkansas Senate Pro Tempore Jim Hendren, R-Gravette, said they hoped to pass a bipartisan package of ethics laws during this year's session.

In opening the 2019 legislative session in January, Hendren addressed the wave of political corruption charges against former legislators, saying "the culture of greed and corruption is over."

At that time, five former state House and Senate members had pleaded guilty or been convicted in ongoing federal probes -- former Sens. Jon Woods and Jake Files, and former Reps. Micah Neal, Eddie Cooper and Wilkins.

Hutchinson, Hendren's cousin, already had resigned his Senate seat after being charged last year in federal court in Little Rock with wire and tax fraud, accused of misspending campaign donations and underreporting his income on federal tax forms.

By the legislative session's end last month, state lawmakers had passed three of six proposed bills. None of the new laws require Arkansas House members, along with state senators, to reveal their business incomes from lobbyists.

"We've made progress," Hendren said at session's end. "We can make more progress."

Information for the article was contributed by Michael R. Wickline of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

SundayMonday on 05/26/2019