The circus was coming! The circus was coming! But not until later in 1919. In the first week of November, Little Rock's scheduled excitement was grand opera.

The famous Chicago Opera Company visited Camp Pike's 3,000-seat Liberty Theatre in North Little Rock for what the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat dubbed "the season," the very short, two-show season. It was no circus, but still it was very grand.

First, the company staged Verdi's Aida, starring famous songbird Rosa Raisa. Then came Puccini's Madame Butterfly, with the excellently Japanese prima donna Tamaki Miura as Cio-Cio-San. She was tiny, and she was totally Japanese and also famous. Singing with her would be the famous Clarence Whitehill as Sharpless — "and he is said to be the best in that role on the operatic stage," the Democrat said.

Sixty musicians in the orchestra, 60 in the chorus. Famous Pavley Russian Ballet with the famous Anna Ludmila, premiere danseuse. All of it arriving at Union Station on a special train with nine coaches and seven baggage cars.

The timing could not have been better for art appreciators. A statewide convention brought 3,000 teachers to town, and the new Fine Arts Club had an exhibit of paintings by reportedly famous artists hanging at the American Bank and Trust Co. downtown. Stores were offering specials on fancy opera clothes. Poe's Shoes even had $10 Grand Opera Pumps in the "Miura" style.

The Liberty Theatre at Camp Pike is described in a 1921 report by the U.S. House Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department as one of 42 Liberty Theatres built by the government in training camps. They varied from 1,000- to 3,000-seat buildings. "And they are equipped in every particular with scenery, drop curtains, special lighting apparatus for stage effects and, indeed, all necessary machinery to give any type of theatrical performance," the report states.

Touring companies were engaged by an office in New York and routed from camp to camp on a percentage basis of the gross receipts. The government built the theaters, but funds for the circuit came from admission fees and the sale of ticket coupons called "smileage booklets."

First up was Aida on the night of Nov. 1, a Saturday. The Democrat and Gazette published their reviews Monday, but the Sunday morning Gazette carried a news report on Page 1:

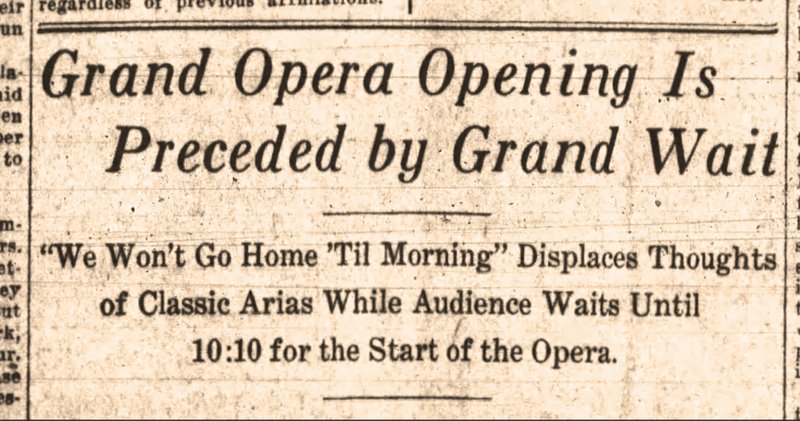

Grand Opening is Preceded by Grand Wait

The performance was set to start at 8 p.m. sharp "with lots of emphasis on the sharp," the report noted. And so the audience rolled in at 7:30.

Big limousines drove up in front of the theater, and fashionably dressed women and their escorts stepped out. Persons from all over the state, including about 1,000 schoolteachers, poured into the large auditorium.

At curtain time, a stage manager appeared onstage. The scenery had been late in arriving. The production would not begin "for several minutes."

After 30 minutes in which the audience buzzed to itself, the official reappeared. It would be "about 30 minutes" before everything was ready.

Everybody who has had anything to do with grand opera knows that it requires three to four hours for completion. The audience began to wonder when it would get back home — that eight-mile drive to town stared them in the face.

Thirty minutes later, the company decided to raise the curtain to help the crowd pass the time. For the next hour and 10 minutes, they gazed upon the overall-bedecked stagehands making an honest living. Women lined up at the theater phone to call home.

At 10 p.m., someone started singing, "We Won't Be Home Till Morning," and the whole audience joined in.

Ten minutes later, the grand opera commenced. It ended at 1:30 a.m.

The Democrat's review by editorialist Paul R. Grabiel, who had been a boxing promoter at Camp Pike, began:

If the spirit of Guiseppe Verdi still haunts the world, and broods over the production of his heaven-born "Aida," it must have gone back to its Elysian bower Sunday morning with a rich contentment.

The audience had bathed and reveled in languorous sweetness spiced with tragedy, and "were thankful to have lived to such an hour."

The Gazette was equally if less grandiloquently grateful.

Today we have YouTube, and we can hear recordings of these voices by searching for their names. I found Raisa singing songs from Aida and also a 1917 recording of Miura singing Butterfly.

The company staged Butterfly that Monday night. While both Grabiel and the unnamed Gazette reviewer praised the "rare" excellence of the orchestra and the "fine" and "splendid" everything else, the Gazette tried to analyze how Miura had made an effective heroine despite not being the best singer. There had been "notes that are harsh here and there." But any defect in her voice was fully atoned for by her natural acting:

She lives the part of the unfortunate Japanese victimized by the perfidy of her lover. She acts and talks with her hands — and the tiniest, prettiest little hands imaginable — and so enlists the sympathies of her audience that there were women last night furtively wiping their eyes in the final act when she realizes that she is deserted and ends her life.

Despite "here and there notes not wholly agreeable," she had "some beautiful tones."

Grabiel, on the other hand, was enraptured.

Rare, truly, is the actress with such superlative art. ... The critic who could find harshness or discord in such a voice, or do aught but wonder at its beauty, range and power, must be captious indeed. ...

Here was a diminutive flower of the Orient, a scant four foot ten in height, exquisitely dainty and charming, transplanted to the American grand opera stage and there measuring up to and exceeding its most exacting standards. ... Here was a real "Butterfly" from the Land of Cherry Blossom, bringing to the Puccini opera all the beauty and charm of Oriental femininity ...

It is worth noting that the Gazette was a morning newspaper and the Democrat came out in the afternoon.

Grand opera. Purple prose. Paintings, limousines, editorial disagreement!

And the circus would arrive in just two weeks.

WE BE @

The standard email address has two parts, a username and a domain name. Between and linking them is the "at" sign, @. Experts debate how and why this (possible) ligature of the letters e and a arose. A case is made for its origin having been retail practice: According to Smithsonian Magazine, the first documented use of the snail-ish character was in reference to quantities of wine in a list by a 16th-century Italian merchant.

In my dad's Firestone store a million years ago, clerks used @ to mean "each at": four 6.95x14 tires @ $31.53.

For email uses, @ might as well mean at as in "where."

Where I, user cstorey, am — the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette newsroom — has a new domain, and so my email address has changed. The old one will work for a while, but as of now my inbox is at:

cstorey@adgnewsroom.com

Style on 11/04/2019