Well I hope we're not too messianic or a trifle too satanic

We love to play the blues

-- Mick Jagger, "Monkey Man"

There are no outtakes, no bonus tracks, on the just-released 50th anniversary edition of the Rolling Stones' Let It Bleed.

So to justify the $124.99 suggested retail price, the set offers newly remastered (by Bob Ludwig) stereo and mono versions of the album on vinyl record and Super Audio CD (SACD), along with an 80-page hardcover book with text by David Fricke and photos by the band's tour photographer Ethan Russell.

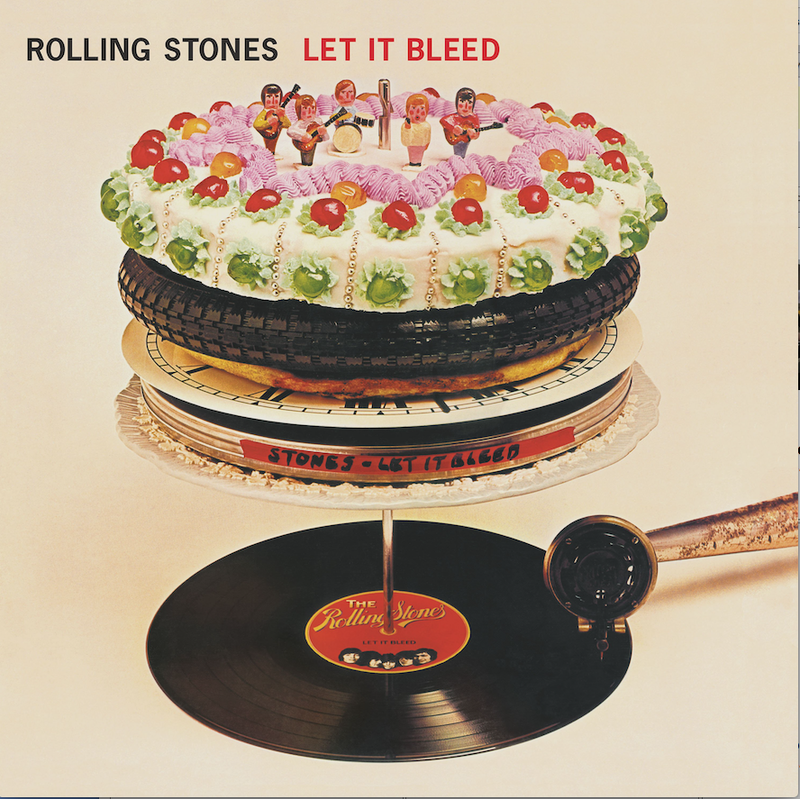

There's a big poster and some hand-numbered auto-signed lithographs printed on embossed archival paper of the album's cover concept art. In his 1969 review in Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus decried it as "the crummiest cover art since Flowers, with a credit sheet that looks like it was designed by the United States Government Printing Office."

The Ludwig mix is fine but not revelatory, which is probably as it should be since Let It Bleed has always sounded fine. It is one of the Stones' best records from what is arguably their best period.

While Brian Jones' loyalists will dissent, the Stones were at their peak from 1968 to 1973 and their run of Beggar's Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street might be the best consecutive four-album run ever.

Certain audiophiles might be excited about the mono versions, as the original mono LP is a fairly rare artifact, but this excitement should be tempered by the knowledge that the original mono mix of Let It Bleed was simply a folded-down version of the stereo mix, which was always meant to be definitive.

Let It Bleed was originally mixed not for car radio speakers but for home stereo systems, and that highly-sought-in-some-quarters monaural mix was an afterthought. But if you want mono, they've got mono here.

It's more appropriate in the replica seven-inch single 45 ("Honky Tonk Women" backed with "You Can't Always Get What You Want") that also accompanies the set. That single was mixed in mono, and "Honky Tonk Women" wasn't included on the album but released as a single five months before the LP was released on Dec. 5, 1969.

The album does include "Country Honk," a countrified version with slightly altered lyrics. (Instead of meeting a "gin-soaked bar-room queen in Memphis," the protagonist of "Country Honk" is "sittin' in a bar, tipplin' a jar in Jackson.")

It has been alleged that "Country Honk" was arranged by Gram Parsons in exchange for the Stones' allowing the Flying Burrito Brothers to record and release the first commercially available version of "Wild Horses," but this seems to be an overstatement. Parsons' sole contribution to "Country Honk" is recommending that the Stones enlist future Burrito Byron Berline to play fiddle on the song. Berline recorded his part on a Hollywood sidewalk, which accounts for the traffic noise and car horn heard on the track.

I used to think that "Country Honk" was a cruel joke the Stones played on their fans or an attempt at maximizing profits. I thought they left "Honky Tonk Women" off Let It Bleed so that people who wanted the song would have to buy the single or the inevitable Greatest Hits package which would include it.

But after almost 50 years, I'm ready to concede the discreet charms of "Country Honk," like Mick Jagger's cockney hillbilly vocals and especially the acoustic snap and shuffle of Keith Richards' acoustic guitar. (Mick Taylor is on there too, playing slide on a Selmer Hawaiian guitar that was little more than a toy.)

But while "Country Honk" might well be the earlier version of "Honky Tonk Women," and the version most obviously in debt to Hank Williams' "Honky Tonk Blues," it's not the game-changer that the single was. Famously, "Honky Tonk Women" was the coming-out party for Taylor, Brian Jones' replacement in the band, and his lead guitar on the single, Richards admitted, elevated the track from studied homage to a country master to the template for a new generation of Stones material.

This was the song on which Richards first applied the open G-tuning he'd learned from Ry Cooder (though Keef isn't sure whether or not he removed the superfluous low E-string on the track) and the scales fell from his eyes and fingers. "Honky Tonk Women" is the point where, for better or for worse, the Rolling Stones left Jones behind.

While Jones was officially a member of the Stones throughout most of the Let It Bleed sessions -- he was officially fired from the band on June 8, 1969 -- he appears on only two tracks. He plays autoharp on "You Got the Silver" and percussion on "Midnight Rambler." Taylor also appears on only two tracks, the aforementioned "Country Honk" and "Live With Me," which was the first time he played electric guitar on a Stones record.

So Richards plays most of the guitars on Let It Bleed, lightning-forking through a dark muddy soundscape of earth-toned blues. Jagger slurs and stumbles more than prances, weaving his drunken, murderous, priapic path, wearing his Mick Jagger mask.

(Marsha Hunt met Mick Jagger about that time; the Stones had contacted her about posing for the sleeve of the "Honky Tonk Women" single, and while she didn't want to do that, she did want to meet the singer. When she did, she was taken aback by his bad complexion, dirty hair, social awkwardness and shyness. They became lovers and had a child, and she probably inspired the song "Brown Sugar.")

And at times, the record gets really real.

Like right from the beginning, with "Gimme Shelter" where backup singer Merry Clayton -- who contributed overdubs from Los Angeles -- determined to "blow [Jagger] out of the room." When she howls, "Rape, murder/It's just a shot away, it's just a shot away" you can feel the walls crumbling, the very foundations of society shaking.

Much has been written about the maleficent end of the '60s -- it's instructive to note that the Stones took the stage in Altamont on Dec. 6, 1969, the day after Let It Bleed was released (though it wasn't this song or "Sympathy For the Devil" they were playing when Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death but the causally misogynistic "Under My Thumb," which sounded like bubble gum compared to the Stones' new material).

"Gimme Shelter" is followed by a remarkable, poignant version of Robert Johnson's desolate "Love in Vain," fleshing out Johnson's skeletal work with Ry Cooder's mandolin and extra chords, and beautifully pealing electric slide work by Richards (who also played an acoustic instrument).

That's followed by "Country Honk," which in the context of the album, seems to make perfect sense (even if "Honky Tonk Women" still seems the superior track) and then "Live With Me," which is notable for being both Taylor's and saxophonist Bobby Keys' first track with the band, as well as being the only Stones track that Leon Russell ever played on.

'BLEED' TALES

The song "Let It Bleed," while providing the album its title, is simply solid Stonesy rock -- the sort of semi-evocative, sub-Dylan lyric ("I was dreaming of a steel guitar engagement/When you drank to my health in scented jasmine tea") Jagger seemed to turn out effortlessly in those days, backed by a sturdy, confident band. It's not the best song on the album, much less of the period, but if you wanted to let someone know what rock 'n' roll sounded like in 1969, you could do worse than play them "Let It Bleed."

(The line "let it bleed" doesn't appear in the lyrics. Richards said Jagger wrote a line that contained the phrase, but they later dropped it and took it for the title after trying some others. And while a lot of people assume that Let It Bleed is either a jibe or inside joke playing off the Beatles' Let It Be, the Stones' release came out five months before the Beatles album. While it's possible, maybe even likely, that the Stones had heard the track "Let It Be" while recording Let It Bleed, it's not inconceivable that the similarities in the album titles are a complete coincidence.)

Side Two kicks off with "Midnight Rambler," Chicago blues about Albert DeSalvo, who confessed to being the Boston Strangler, that Jagger and Richards had written in sunny Italy the year before. (Jones is credited with playing congas, but if you can hear him you've sharper faculties than most of us.) That's followed by "You Got the Silver," which is in the running for Richards' best vocal performance as a Stone. (I'd rate it just behind "Before They Make Me Run.")

Then it's back to Jagger with "Monkey Man," a rocker that splits the difference between Chuck Berry and David Lee Roth.

All that's left is the finale, "You Can't Always Get What You Want," a William Burroughs-esque story of frustration and resignation punched up by the off-kilter stylings of the London Back Choir.

Al Kooper remembered the session this way:

"[Producer] Jimmy Miller sat down at the drums and remained there playing on the take. Charlie [Watts] was not happy but was graceful about it. Mick and Keith played acoustic guitars, I played piano, Bill [Wyman] was on bass and Brian lay on his stomach in the corner reading an article on botany throughout the proceedings. I then overdubbed the organ."

"You Can't Always Get What You Want" remains one of the most outrageous and ambitious productions ever committed to a rock 'n' roll record, a mini-opera that opens with a stately choral section, a kind of U.K. parody of a black gospel choir that gives way to one of Jagger's least-affected vocals, supported in turn by waves of Kooper's throbbing organ, Richards' discursive electric guitar and some lovely piano work.

It feels autobiographical -- this is Mick's song; he had it all worked out in his head -- and elliptical, a cinematic story of a resigned rock singer who is way past expecting satisfaction. After encountering a strung-out girl -- an old flame or drug buddy -- at a party, he goes down to the demonstration, "to get my fair share of abuse" and eventually ends up in a drugstore talking with Mr. Jimmy (misheard sometimes as "Mr. Jitters") with whom he has a soft drink -- cherry red:

I sang my song to Mr. Jimmy

And he said one word to me

And that was death

Yeah, you can't always get what you want. But in the end, we all get what we need.

If you want to mark the spiritual end of the Sixties (as opposed to the 1960s) with the murder of Meredith Hunter at Altamont -- or when the last helicopter filled with American personnel lifted off a Saigon roof in 1975 -- you'd be hard-pressed to find a better soundtrack than Let It Bleed.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 11/10/2019