A number of Arkansas dams whose failure would have the potential to cause death are in "poor" or "unsatisfactory" condition, and some have no emergency action plan for such a failure, according to state data obtained by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Specifically, the state found 23 dams in sub-optimal conditions, although some dam owners told the newspaper that they have addressed issues raised in their most recent inspection reports. The state also found four such dams without emergency action plans, which include projections of where flooding would occur in the event of a failure. One person told the newspaper that his neighborhood's dam had developed an emergency action plan since it had last been inspected.

The state has data on more than 1,300 dams but regulates only about one-third of them. Only 114 of them are high-hazard, which means a failure has the potential to kill. Those 23 poor-condition dams are high-hazard.

Most of Arkansas' dams are earthen dams. A plurality of them are built for recreation. About half of them are older than their 50-year design life.

"The infrastructure, as it relates to dam safety, is not great across the country," said Stephen Smedley, an engineer in the dam safety and floodplain management section at the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission.

The state's dam condition ratings are subjective, and there's no nationwide guidance or standard for how dams are assessed. A Federal Emergency Management Agency grant to every state requires a condition assessment, so states apply the same ratings using varying methodologies. In Arkansas, points are based on conditions, spillway design, seismic zone, potential hazard and whether an emergency action plan is in place.

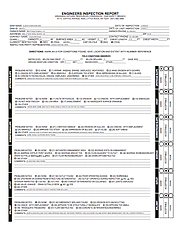

In addition to the condition assessment, the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission fills out engineering inspection reports with alternate evaluation categories. It then sends letters to dam owners, which at times contrast with what the condition assessment data says about the dams.

One dam owner told the newspaper that he was sure state officials would say his dam is in "great" shape, when in fact the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission has rated his dam as "poor."

In the June 26 letter to the dam operator, Lakewood Property Owners Association in North Little Rock, the commission doesn't use the words "poor" or "great" but states that the dam "has a few defects that are cause for concern."

Several letters to the owners of problematic dams characterized the dams as being in "good condition," while noting a few issues the owners should work on.

Smedley acknowledged the discrepancy in how conditions are communicated.

But nearly every time, dam owners respond to whatever deficiencies are identified in those letters, he said. Those that don't can be served consent forms that would give the commission greater oversight and control of how the owners repair the dams. The caveat, he said, is that the owners must sign the forms.

The newspaper requested the most recent inspection reports and letters to dam owners for each of the 23 dams, but it sometimes received letters referencing more recent inspections than the ones in the obtained reports, or vice versa.

The newspaper attempted to call each of the 23 dam owners. It reached several, who explained how their dams' conditions may have changed since the last inspection reports or how they intended to fix the defects. Several other owners could not be reached. Some did not respond to messages, and others did not have current contact information within state records.

NATIONWIDE PROBLEM

A more than two-year investigation by The Associated Press has found scores of similar dams nationwide. They loom over homes, businesses, highways or entire communities.

A review of federal data and reports obtained under state open records laws identified 1,688 high-hazard dams, rated in poor or unsatisfactory condition, as of last year in 44 states and Puerto Rico.

The actual number is almost certainly higher. Some states declined to provide condition ratings for their dams, claiming exemptions to public record requests. Others simply haven't rated all of their dams because of a lack of funding, staffing or authority to do so.

Deaths from dam failures have declined since a series of catastrophic collapses in the 1970s prompted the federal and state governments to step up their safety efforts. Yet about 1,000 dams have failed over the past four decades, killing 34 people, according to Stanford University's National Performance of Dams Program.

Built for flood control, irrigation, water supply, hydropower, recreation or industrial waste storage, the nation's dams are more than a half-century old on average. Some are no longer adequate to handle the intense rainfall and floods of a changing climate. Yet they are being relied upon to protect more and more people as housing developments spring up nearby.

"There are thousands of people in this country that are living downstream from dams that are probably considered deficient given current safety standards," said Mark Ogden, a former Ohio dam safety official who is now a technical specialist with the Association of State Dam Safety Officials.

The association estimates it would take more than $70 billion to repair and modernize the nation's more than 90,000 dams. But unlike much of the nation's other infrastructure, most U.S. dams are privately owned. That makes it difficult for regulators to require improvements from operators who are unable or unwilling to pay the steep costs.

"Most people have no clue about the vulnerabilities when they live downstream from these private dams," said Craig Fugate, a former administrator at FEMA. "When they fail, they don't fail with warning. They just fail, and suddenly you can find yourself in a situation where you have a wall of water and debris racing toward your house with very little time, if any, to get out."

INSPECTIONS IN U.S.

The Arkansas Natural Resources Commission tries to inspect each high-hazard dam annually, although FEMA only requires it every five years.

Some states never inspect low-hazard dams -- though even farm ponds can eventually pose a high hazard as housing developments encroach.

Ratings are not always publicly disclosed. The U.S. government will not disclose conditions, but states often will.

The AP examined inspection reports for hundreds of high-hazard dams in "poor" or "unsatisfactory" condition. Those reports cited a variety of problems: leaks that can indicate a dam is failing internally; unrepaired erosion from past instances of overtopping; holes from burrowing animals; tree growth that can destabilize earthen dams; and spillways too small to handle a large flood. Some dams were so overgrown with vegetation that they couldn't be fully inspected.

Georgia led the nation with nearly 200 high-hazard dams in unsatisfactory or poor condition, according to the AP's analysis.

In Arkansas, one owner had three dams among the 23 rated as a high hazard: the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

That was a surprise to Kevin Mullen, the Game and Fish Commission's operations chief.

Mullen has never received a condition assessment from the state for the Game and Fish Commission's 40 dams, only the letters from either the state or the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resources Conservation Service. (The federal Natural Resources Conservation Service inspects some dams in Arkansas, but most are inspected by the state Natural Resources Commission.)

Nonetheless, the Game and Fish Commission knew of the issues with its dams and has taken steps to address all of them, he said. In Washington County, the Game and Fish Commission has finished the engineering design on a new spillway for Lake Elmdale, replacing the current undersized one. Construction is pending.

Some unregulated -- and thus, uninspected -- dams can pose concerns to state officials, too.

The Lake Sandy dam, located in a Saline County subdivision, was about to burst a couple of weeks ago, Smedley said. Officials have been monitoring it and visiting it for months. It's 2 feet too short to be regulated in Arkansas, although it would be regulated under the laws of most of Arkansas' surrounding states.

The dam avoided a breach this fall after water levels dropped, but Smedley said he's still concerned about the dam because of the winter rainy season. He plans to petition the county judge of Saline County to destroy the dam through a controlled water release. That would turn the lake -- around which the subdivision developed decades ago -- back into a creek.

"It's a big deal to do something like that," Smedley said. Many property owners may not be happy, he said, and their property values will decrease.

The newspaper reported on the Lake Sandy dam last fall. It had long been neglected by a divisive property owners association.

Smedley said he appreciates what dams can do, such as building lakes for drinking water. But sometimes it's better not to have one, he said.

"The safest dam is one that doesn't exist," he said.

SPENDING ON DAMS

In a 1982 report summarizing its nationwide dam assessment, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said most dam owners were unwilling to modify, repair or maintain the structures, and most states were unwilling to spend enough money for an effective dam safety program.

Since then, every state but Alabama has created a dam safety program.

But the recession a decade ago forced many states to make widespread budget and personnel cuts. Since a low point in 2011, states' total spending on dam safety has grown by about one-third to nearly $59 million in fiscal 2019 while staffing levels have risen by about one-fifth, according to data collected by the Corps of Engineers.

California, which runs the nation's largest dam safety program, accounts for much of that gain. It boosted its budget from $13 million to $20 million and the number of full-time staff members from 63 to 77 after the failure of the Oroville Dam spillway in 2017.

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials said almost every state faces a serious need to pump additional money and manpower into dam safety programs.

A new $10 million grant program run by FEMA will fund projects for high-hazard dams that have fallen short of safety standards and pose an unacceptable risk to the public.

The first round of grants announced this fall will go to projects in 26 states. They will pay for preliminary steps such as risk assessments and engineering designs, but not the actual repairs. State or local entities are to provide a 35% match.

Over the past decade, FEMA's various programs have provided more than $400 million for projects involving dams, mostly to repair facilities damaged by natural disasters. Until now, no national program had focused solely on improving the thousands of dams overseen by states and local entities.

The new Rehabilitation of High Hazard Potential Dams Grant Program was authorized by a 2016 federal law to supply $445 million over 10 years to repair, improve or remove dams. But Congress didn't fund the $10 million authorized allotment for fiscal 2017 or 2018, and it funded just $10 million of the $25 million authorized for fiscal 2019.

Smedley said he hoped to discuss potential projects with dam owners once a new round of funding comes along.

Currently, the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission receives less than $100,000 annually in FEMA grant funding. That pays for inspections, Smedley said, but not much else.

Information for this article was contributed by David A. Lieb, Michael Casey and Michelle Minkoff of The Associated Press.

A Section on 11/18/2019