Brian Smith, of Winter Park, Fla., never knows what's going to come in the door. Customers have brought in dead scorpions, locks of hair, broken plates, bricks from famous places, pawprints, President Bush's socks, and a metal bell from a Yemeni yak's neck, all for him to display.

"I've seen some weird stuff," said Smith, owner of Corners Custom Picture Framing, who's been framing you name it for 20 years. "The strangest was the lady who brought in three umbilical cords."

It is a Saturday afternoon. I am perched on a stool in Smith's workshop watching him ply his craft and chatting about the under-appreciated art of custom framing, not expecting this. I scooch forward because no one can hear about the time a customer walked in with three umbilical cords and not want the rest of the story.

The dried-up (thank heaven) cords accompanied photos of the woman's three sons, Smith continued. She wanted their pictures framed with their corresponding umbilical cords.

"How did she know whose was whose?" I asked.

"Oh, she knew!" Smith said, adding that he entered the project that year in an industry contest for who framed the weirdest thing.

"Who could top that?"

"I lost!" he said, still stunned, "to someone who'd framed the remnants of a circumcision."

"I bet that kid's in therapy."

The point of this little narrative is that if it means something to you, it can probably be framed, and also that meaningful is relative.

"I don't judge," Smith said. "I would never say not to frame something, but I do once in a while wonder."

On most days, however, Smith frames more expected items: prints, paintings, posters, photographs, fine art, and sports memorabilia. On this day, two college diplomas sit on his worktable, waiting for mats and frames. Next up is a 24-by-36-inch oil painting on stretched canvas, which he plans to float mount.

"Half the fun of my job," he says, "is hearing the stories. And when you've been doing this as long as I have, you get to know the families. I've framed the booties of kids who are now customers."

The other half of the fun is witnessing the transformation. A good framer can elevate the ordinary and make it extraordinary, can make tired art look new again, and can refresh a whole room by simply reframing its art.

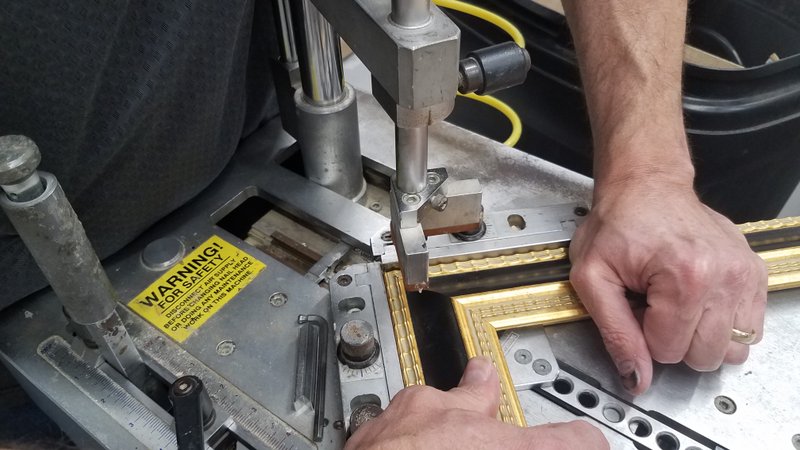

As we talk, he uses a black Expo marker -- because black Sharpie ink turns purple over time -- to color the inside corner edges of a black frame he's building, so when he miters the corners no white line peeks through.

"I'm known for my corners," he said.

"I can see why."

"Little imperfections drive me nuts."

I like that in a framer.

During my afternoon in his workshop, I learn more trade secrets:

What's in a mat. A well-chosen mat not only enhances art, but also separates glass from art. "You don't want to put art, especially photos, directly against glass," he said. "You want a spacer or a mat in between." Mat color, texture, layers, and thicknesses are also considerations. While a well-chosen colored mat can marry art to decor, 75% of mats are neutral for good reason. The wrong color can backfire. That great yellow mat might work with the art but not with the room. It can also make art harder to relocate.

The outer edge. Frames should complement, not overpower what's in them, Smith said. "If the frame takes your eye away from the art, it's a failure." That said, if you have the room, don't be afraid to go big. Skimpy is wimpy.

Keep it clean. Dust, dirt and fingerprints inside the glass are a framer's nightmare. Use ammonia-free glass cleaner to wipe the glass until it is streak free and clean. Clean the side that faces the art first. Catch the outside later. Next make sure the art and mat you're covering are also dust and debris free before marrying the pieces.

Go acid free. If you want what you're framing to last, use archival-grade materials, which are acid free. Regular matting, cardboard and foam core contain acid, which will cause pieces to discolor and deteriorate faster. "This is not just a ploy to charge more," Smith said.

Make a clear choice. Most framers offer a choice of regular, nonglare, or museum quality (least reflection, most expensive) glass. For large pieces, plexiglass is also an option because it weighs less. Each of these choices comes with or without UV coating. While UV or conservation coating will tint the glass slightly, it protects what's inside from light damage. (Even indoor lights can cause fading.)

Consider the room. When done right, a great frame should complement the art and the room it's in. Because most framers see only the art, customers need to make sure the frame fits the room's decor, in color and style, and the wall it's going on. Bringing a picture of the room to show the framer helps a lot, said Smith, who suggests using painter's tape to outline the dimensions on the wall.

The price tag. Because of all that's involved, custom framing adds up. For instance, an 11-by-14-inch college diploma, like the ones on Smith's worktable, will cost $200 or more to have custom framed, a small price considering what that education cost. And the cost of framing that umbilical cord? Priceless.

Syndicated columnist Marni Jameson is the author of five home and lifestyle books, including Downsizing the Family Home -- What to Save, What to Let Go

HomeStyle on 10/05/2019