BENTONVILLE -- Consider the crystal.

A crystal is a solid in which constituent molecules or atoms are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern, distinct from the arrangement of atoms in an amorphous solid. The surface geometry of a crystal reflects its internal geometry.

“Crystals in Art: Ancient to Today”

Through Jan. 6, Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Hours: 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday, 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Wednesday-Friday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday, closed Tuesday

Admission: $12.24. Admission to the permanent collection is free.

(479) 418-5700. crystalbridges.org

All crystals are transparent in the sense that the outside reflects the inside. Aluminum oxide crystal appears completely clear because the spacing of its molecules allows all visible light to pass through it; other crystals are aligned so that only certain wavelengths of visible light can wiggle through without being absorbed. These crystals appear colored.

We might think of crystals in terms of gemstones and heavy expensive glassware, but those glass products are not crystal. The nomenclature derives from 16th-century Murano glassmakers who used select quartz pebbles from the banks of the Ticino and the Adige rivers instead of sand to make what they called cristallo, an extraordinarily clear and colorless glass.

For our purposes, and for the purposes of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, we can think of crystal as quartz, a mineral compound made from silicon and oxygen that naturally occurs as a glassy stone. Pliny the Elder and other ancient Greeks believed quartz was a special kind of unmeltable ice, forged in the fires of Hephaestus.

Some of us believe that crystals have magical properties, that they can heal and protect and realign our chakras. Some of us associate them with roadside attractions and hippy-dippy incense inhalers. But human beings have always believed there is something special about these shiny things with their unnatural-appearing symmetry that look like they must have been carved in heaven.

No wonder we have treasured them and used them to decorate ourselves. No wonder some feel something like pulse or breathing -- some vibration -- when they hold them in their hand.

At first, and even on second thought, "Crystals in Art: Ancient to Today" seems like an odd exhibit for Crystal Bridges to tackle. With 75 objects including artworks and artifacts, as well as 10 crystal specimens, it feels more like something one might encounter in a museum of natural history, something science-y. Yet when you consider Arkansas' special relationship to "rock crystal" (the transparent, colorless variety of macrocrystalline quartz) it begins to make sense.

American geographer and geologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft wrote the first European account of Arkansas rock crystal in 1819. In the Ouachita Mountains, he discovered places where quartz covered the ground: "very pure and transparent, and beautifully crystallized in six-sided prisms, terminated by six-sided pyramids."

Something like 80% of the planet's rock crystal now comes from Arkansas, which, as Lauren Haynes, the museum's curator of contemporary art, says "has often been called the quartz crystal capital of the world."

So why not gather artifacts and artworks from all over the world to tell the story of human romance with these stones? One of the things a museum ought to be able to do is contextualize art and demonstrate how materials and utility interact with artistic expression. A dithering of boundaries is always a good thing -- though crystals serve to remind us that straight edges and defined points of delineation do occur naturally.

As might be said of most of the major exhibits mounted by Crystal Bridges, there's something for everyone here. It's accessible but not dumbed down (although some supplemental explanatory text remained to be added on the press preview day). It contains paintings, sculptures and pieces of a conceptual nature, including an installation (Dozing Consciousness, 1997) that consists of a looped video of the face of provocative Serbian-born performance artist Marina Abramovic as she seems to sleep submerged in a bath of discrete crystals.

It's divided into five sections, each featuring art and artifacts from different periods that approach the ways various civilizations have related to crystal. The first, "Sacred and Transcendent," is concerned with the ways qualities of crystal have sparked spiritual devotion and includes one of the exhibit's oldest man-made relics, an Egyptian Taweret figure dated from between 532-332 B.C.

Taweret ("the Great Female") is the ancient goddess who protected pregnant women. This depiction, a sliver more than 4 inches tall, represents her in human form with the head of a hippopotamus.

Nearby sits a Thai Buddha of similar size, carved from rock crystal with a headpiece of gold and rubies. It's much younger than the Taweret figure, said to be from the 15th or 16th century, but one imagines it was cut from the stone in much the same way, with the same rounded shoulders and softened arms and suggested features.

Contrast this with a Mexican rosary pendant, also from around the 16th century, which features a stylized crystal skull. Later, the gallerygoer will encounter a Roman statuette from the first century B.C., presumably of Venus, its limbs and head snapped off.

All of these unknown artists were working much the same way, in different parts of the world, to produce works that feel imbued with a sense of the sacred. There is a universal perception of crystal as a material worthy of being ensconced in temples and handled by priests.

Abramovic is a believer in the mystic power of crystals; in an interview published in the exhibition catalog, she tells co-curator Joachim Pissarro: "Crystals send certain energy which is undeniable. Crystal was used in the Middle Ages and now it's used in technology. It has the power of conserving energy and light."

She plans on constructing a crystal chamber using "lots of crystals that will emit certain types of vibrations that will positively [affect] ... visitors."

The crystals "will purify their energy because we are all built from energy and light," she tells Pissarro, the great-grandson of impressionist Camille Pissarro and an art historian/theoretician. "It will be very special for the public right now, at a time when stress and unbalance rule our daily lives. It could create a nucleus where you can feed on the energy of the crystals and stabilize your own energy."

The second section of the exhibition, "Crystal Extravagance," examines the material as a signifier of wealth and status, as conspicuously consumed objets d'art. But among the House of Faberge cigarette cases and an elaborately jeweled flask from 17th-century India stands Marilyn Minter's remarkable Crystal Swallow, a large (96-by-60-inch) enamel painting on metal of a heavily lipsticked presumably female mouth, seeming to ingest (or expel) a number of faceted gems, which could be taken to be crystals or diamonds. Drops of perspiration on the lips and skin around the mouth echo the gems, and the painting seems to be in conversation with Abramovic's video installation in the previous section.

If the buried face in Dozing Consciousness can be seen as being animated by the crystals that lie on it; if the piece seems to transmit a certain peacefulness and relaxation, reinforced by the alternate soft sounds of breathing and tinkling stones on the soundtrack, Crystal Swallow suggests a kind of assault, a drowning of the face in these symbols of luxury. Minter's painting isn't of a woman relaxed and re-invigorated by healing stones. There is panic and horror in this sleek critique of fashion iconography.

Another striking thought-provoking piece appears a little later in the gallery; a large skull, carved from rock crystal, that looks like it might have come from the prop department of an Indiana Jones movie. It was alleged to be an ancient Mexican artifact, but it turns out it was made by a forger, probably in the 1950s. It's as cool as a tail-finned Cadillac.

The third section of the exhibit is titled "Science and Mysticism," and its highlight might be Albrecht Durer's famous 16th-century engraving Melencolia I, a symbol-rife engraving that depicts a brooding angel surrounded by tools and implements, including what appears to be a crystal ball and a large crystalline block.

There are two photographs in this part of the exhibit that prominently feature crystal balls: Jacque-Henri Lartigue's 1931 photo of Romanian fashion model Renée Perle holding a large glass globe while dressed in the stereotypical costume of a gypsy fortune teller, and Cindy Sherman's enigmatic Untitled #296, 1994, a self-portrait of the artist presented as a kabuki contemplating a mirror ball she holds in her left palm.

The star of the fourth chapter, Crystallic Form, is the largest crystal cluster yet found in Arkansas, a five-foot-tall chunk pulled from the ground by miners working the Zigras Mine in Blue Springs near Hot Springs in 1931. Considered the single most important quartz specimen mined in America, The Holy Grail, as it has been dubbed, features a four-foot-long point rising from its matrix and is estimated to weigh about 1,500 pounds. It's part of Crystal Bridges' permanent collection and has been moved from its usual location in the south lobby for this exhibition.

In counterpoint to this naturally occurring phenomenon, the curators have brought in contemporary works by the likes of Andy Warhol (a series of silk-screened prints depicting gemstones) and put forward the interesting idea that crystal forms might have inspired the spatial geometry of cubism. Pablo Picasso's 1918 painting Guitare and Juan Gris' 1916 painting Guitare sur une Table are presented as examples.

Ohio-born artist Daniel Arsham's whimsical sculpture Blue Calcite Column of Footballs, 2016, in which he strings some 20 ravaged footballs (cast from Hydrostone and embedded with blue calcite crystals) arranged into a kind of rosary chain and stands them improbably on end, made me wonder if his creation of this future relic is somehow informed by local enthusiasms for the college game and the late blues-rock band from Fayetteville that was led by Windy Austin and Mike Mohney, Zorro and the Blue Footballs.

(Probably not; Arsham, who lives in New York, was born in 1980, too late for first-hand familiarity with the band.)

The final section, "Crystal Universe," loops back to the beginning, and the imagined (or real) mystic properties of crystal and the way modern artists such as Ai Weiwei have engaged the material. (Typically, Ai's contribution, Chandelier, is both witty and obscure -- it's a working, crystal-dripping light fixture of Seussian complication that stands more than 13 feet tall.)

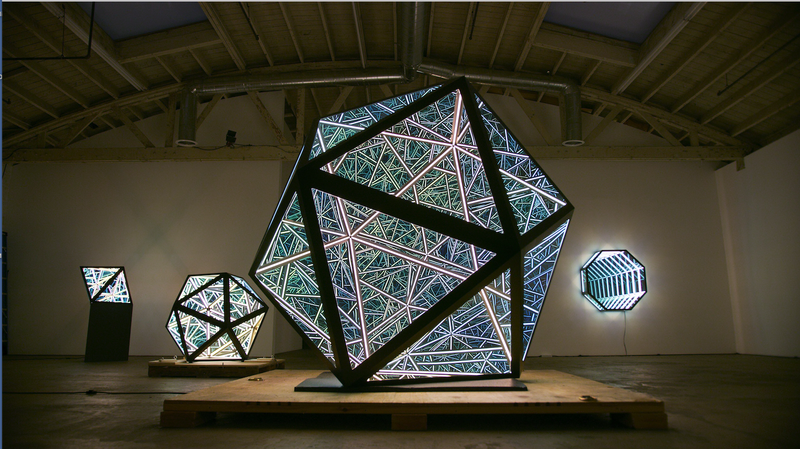

Multimedia artist Anthony James' Portal Icosahedron is sure to be one of the exhibit's more memorable experiences. It's a polyhedron with 20 transparent (one-way) mirror faces enclosing a lattice of LED light bars. Looking into the structure, one sees an infinite reflection of light. (There are actually two sculptures, one 80-by-82 inches, the other about half that size.)

More subtle, but perhaps equally fascinating, Olafur Eliasson's Your Lunar Nebula, a smattering of 100 or so partially silvered crystal balls of various sizes arranged in a loose circular pattern, plays with the viewer's sense of perspective and ability to focus, compounding the world into reversed and upside-down samples that change as one moves around the room.

Eric Hilton's Storm is a static beauty that echoes an exquisite piece of late 19th- or early 20th-century Chinese craftsmanship from earlier in the gallery -- another example of the way these carefully chosen works seem to be in conversation with one another. If the argument they collectively make is for the suitability of this naturally occurring, naturally beautiful material for being worked by human hands, their case was long ago made.

There are also chances to physically experience these crystals, to hold one in your palm or rub it with your thumb and see if you perceive the magic within. There's a small section where the more mundane and practical aspects of crystal are discussed -- the way they can perform as the heartbeat of a cheap but highly accurate wristwatch, the way they can be used in radios and electronic oscillators and piezoelectric pick-ups for musical instruments.

But is that art?

It doesn't matter. It's within the museum's mission of providing a place where wonder might be engendered and curiosity assuaged.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 10/20/2019