For some, it's about holding history in their hands, while for others, it's about holding onto Arkansas' history.

While opening the door to a large walk-in closet, historical archaeologist Jodi Barnes pauses before describing her lengthy involvement in the identification, inventory, research, writings and interpretation of the Native American collections of A.C. Looney and R.H. Kolb for the Drew County Historical Museum in Monticello.

Desha County Museum

264 U.S. 165, Dumas

Hours: 9 a.m.-3 p.m. Tuesday-Thursday; 2-4 p.m. Sunday

Info: (870) 382-4222 facebook.com/deshac…

Drew County Historical Museum

404 Main St., Monticello

Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturday

Info: facebook.com/drewco…

When asked about the amount of time needed for the project, playfully, she says, "Too long," and then explains that originally the museum staff thought it would only take about two months to complete it.

Not so.

It took about two years but her work resulted in the museum's exhibit titled, "Our Past: Arkansas Indians in Drew County," and includes many of the artifacts found by the two men in Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas during the last century.

Barnes is the Arkansas Archeological Survey Station Archeologist at the University of Arkansas at Monticello Research Station and a faculty member. She sees her professional relationship with local museums, teachers and amateur and professional archaeologists as one of educator and consultant.

Pausing before re-entering the closet to fetch a broken pot that's part of the collection but not on display, she admits upon first seeing the museum's disorganized Looney-Kolb collection, "It was overwhelming" and not in a good way.

But Barnes, refusing to shy away from a challenge, got busy.

The project started about five years ago with a student's independent study paper, which morphed into a collaboration between the museum and her office.

A second-story room renovation by museum staff for the collection and funding from the Arkansas Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities made it a reality.

"We had $2,000 in funding," says museum president Tommy Gray. The re-do came from in-kind and private donations, including a few dollars for paint and other supplies from Gray's own pocket.

Barnes says she feels the exhibit illustrates the educational potential of small museum collections, but it also highlights the challenges of interpreting artifacts without context.

"I am proud of the finished project. I think it tells an important story ... about the lives of the people who lived in Drew County for thousands of years," she says.

Amateur archaeologist Curtis LaGrone, who helped with the project, says, it's a "great collection."

THE MAKING OF A COLLECTION

During the last century, American Indian treasure hunting was celebrated. So it was in this spirit while living in Broken Bow, Okla., that Looney started collecting artifacts in 1920.

According to a May 23, 1962, article by Ernie Deane in the Arkansas Gazette, Looney first looked for stone objects in plowed fields, and later discovered "some grave locations, so old that natural forces had long since caused bones to disappear."

A few years later when transferred to Dierks, he met R.H. Kolb, a teacher and collector. Most of his artifacts, Looney told Deane, were "gathered around Dierks, De Queen, Nashville and Horatio," or Caddo country.

Together and no matter the weather, the men spent their weekends for nearly eight years digging together, and according to the article, Looney said, "The results were satisfying."

Upon Kolb's death in 1936, his artifacts went to Looney. Their combined collections included pieces such as small effigy bowls and a couple dozen effigy stones in the shape of animals or birds. A few of those are now included in the collections at the Desha and Drew county museums.

Looney found two ceremonial frog effigy bowls -- possibly made by the Kadohadacho people and included in a burial site -- in Lafayette County in 1962. These are now housed at the Arkansas Historical Commission in Little Rock.

The two men seemed to enjoy the American Indian artifact hunt, and at the end of the article, Deane wrote, "His greatest thrills came, he [Looney] said, from actually finding works of Stone Age Indians, by his own effort."

INSIDE THE MONTICELLO COLLECTION

It's a late morning in mid-July when Barnes is warmly greeted by Drew County Historical Museum president Gray. He's opening the museum to Barnes and her new station assistant, Lydia Rees, who is seeing the museum and the exhibit for the first time.

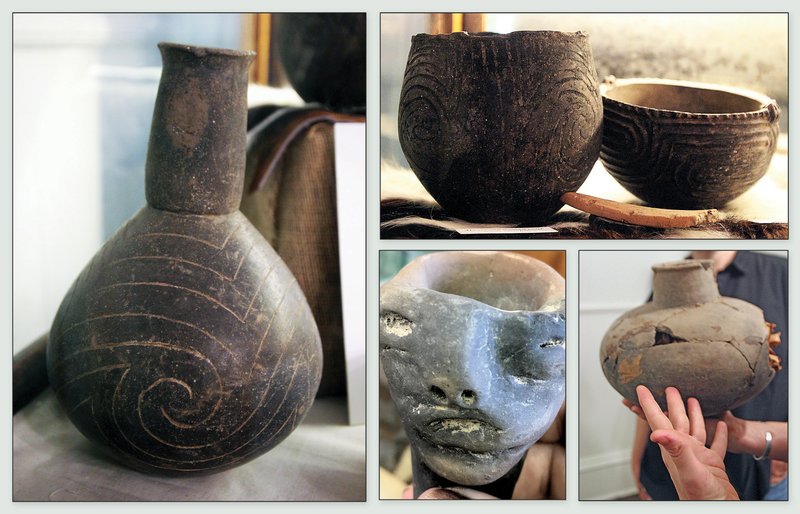

Peering into a case containing a variety of long-necked bottles and bowls, Rees says confidently, "It's Caddo," and judging by the design and elaborate decorations, she adds, "The bottles were most likely found in graves."

She explains the difference in appearance between designs carved into the bottle when the clay was wet as opposed to carving it dry.

It's a clue in determining its origins, Rees says.

Because there's no information about the dig site, Barnes adds, "It's tough to pinpoint an exact date [when the pieces were created]. It could range from about 1500 to 1700."

One of Gray's favorite pieces is a large bottle made from jade.

In addition to the pottery, the exhibit contains a collection of pipes and dozens of points attractively displayed. These come in a variety of colors, reflective of the rock used to fashion it. Dozens more are stored in small flat, glass-fronted display boxes in the closet.

Also kept there, are broken relics that are too fragile to display, along with modern pieces that were mixed in with the authentic ones. That meant Barnes had to ferret out the fakes early in the identification process. It's possible other artifacts became mixed in over time or that Looney or Kolb bought a few modern reproductions, but in Deane's article, Looney claims he didn't buy any.

Barnes says spotting a fake can be difficult for the amateur.

"There are stylistic differences that you notice after seeing the authentic ones, like the expression on the face. People have to be really good and knowledgeable to replicate Indian pottery," she says.

THE ALLURE OF THE PAST

"We encourage visitors," like the 80 Drew Central Elementary School sixth-graders who recently stopped in for a guided tour, Gray says. Most often, kids are first drawn to the points and spears and then to the pottery, and it's hard to miss their enthusiasm.

Barnes says this isn't surprising, "It's so exciting to think of all of the people who held that arrowhead or button before you ... People want to hold history in their hands."

The exhibit explores topics such as early foods, pottery production, flint knapping and includes some kid-friendly materials.

SAVING OUR HISTORY

From the mid-1960s through about 1975, a large portion of the Looney-Kolb collection was on display at the University of Arkansas Museum at Fayetteville, Barnes says.

But that wasn't the entire collection.

According to Deane's article, "At his home in Fordyce [during the same time], Looney has a collection of arrow and spear points, tomahawks and the like that runs into thousands of individual items."

After Looney's death, the family began selling his collection. That decision gave birth to two southeast Arkansas museums in the 1970s.

The Drew County Museum bought a portion of the collection in 1972 for $10,000, with possibly another third going to private collectors who managed to snag some of the best pieces. But no one's certain of what happened to these.

Around the same time, the future Desha County Museum board bought a portion, also for $10,000. It opened in 1979, touting the collection as a main attraction.

Award-winning newspaper publisher/writer Charlotte Tillar Schexnayder, then living in Dumas, was the driving force behind the founding of the Desha County Museum and was eager for the board to purchase the pieces.

"I felt it was absolutely necessary that the collection be kept here ... It's a part of our history," she says.

Her desire that the pieces remain in southeast Arkansas was influenced by a childhood event. During the late 1930s when a teenager, Schexnayder remembers spending days on end watching the excavation of the American Indian mounds located between Tillar and Selma, and often called the Tillar Mounds by locals. These were stored at the Jesse Prewitt family home and Schexnayder, who was studied history, spent much of her free time studying the pots and other pieces.

"I remember seeing those wonderful, amazing artifacts ... The Smithsonian Institution has them now but it was my reoccurring dream to have kept those pieces here," she says.

Now, the pieces are tightly squeezed into a couple of unlighted display cases at the museum while its larger artifacts spill out onto the surrounding floor. It gets lost in a building filled with odds and ends.

Recently, the Desha County Museum was named as one of the Deloris and Merle Peterson Trust beneficiaries and all the details have yet to be officially announced; however, the museum will receive $1.5 million.

Schexnayder says, "We have big dreams for when the Peterson money becomes available."

"It will be a game-changer, and," says Peggy Chapman, director at the Desha County Museum, "the gift will allow the museum to repair and restore some of the old buildings and build a new building."

Also, it will give her the means to redo the Looney-Kolb collection display cases, as well as have it categorized and authenticated. Through Barnes, she learned there were a few fakes or pieces that didn't belong in the collection.

Chapman describes it as "probably the most valuable collection in the museum."

FOR PROFITS OR PERSONAL GAIN

Not only has the verbiage archaeologists use to describe American Indian culture and its heritage changed, but it's no longer acceptable to dig willy-nilly on public or private lands, and it's illegal to unearth Arkansas graves no matter the location. However, it's still happening on private lands and government-funded dig sites.

Barnes says, "We deal with looting."

For example, Barnes is working with a timber company in south Arkansas, that insists on remaining anonymous, mapping the mound sites on their property. She has found about 50 old dig holes.

"People have been digging it for years. There's a newspaper article about Boy Scouts digging up human remains in the 1930s, but we have very little archaeological data from it ... So the bones of the people who built that site may be in someone's attic right now," Barnes says.

She believes the dig site has connections to Poverty Point in Louisiana and was occupied in the Late Woodland and Mississippi periods, or as late as 1400 A.D.

"So this site has the potential to provide all kinds of information about trade and exchange, the domestication of wild plants, and changes in foodways, technology, belief systems, burial practices, and social organization. If a collector was to come forward with the artifacts they recovered, this could tell us important information about the site," she says.

Here and at other locations, she says, it's hard to estimate how much of the state's historical story has been lost to looters and others.

Barnes wishes the dig-it-up-fast-while-trashing-the-site mindset would change, saying when the site information is lost, any interpretation is limited in scope.

"We have fewer stories to tell," she says.

Style on 09/08/2019