FAYETTEVILLE — The Wilson Springs wetland preserve in Fayetteville is officially on its way back to health.

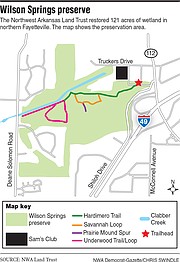

The 121-acre preserve, the largest in Northwest Arkansas, is home to a plethora of vegetation and wildlife. Rare species such as the Arkansas darter fish and Henslow sparrow share the space with deer, bobcats, coyotes, owls and ducks. Spring-fed streams converge to form Clabber Creek.

Native flora have re-sprouted and replaced non-native plants and trees like privet and honeysuckle that stifled the area’s natural beauty and deprived the streams and undergrowth of sunlight.

The transformation took seven years.

Volunteers with the Northwest Arkansas Land Trust removed the invasive overgrowth, by hand and, sometimes, using a contractor and heavy equipment.

Work happened in chunks as grants arrived from the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Future generations now will be able to experience nature amid the extensive development in the area, said Terri Lane, executive director of the land trust.

“It’s just a really magical, natural oasis in the middle of an urban matrix,” she said.

The land trust held a nature and arts festival Sept. 7 to celebrate the transformation.

“Here’s this preserve where you can find some peace and quiet and watch birds and butterflies,” Lane said, noting the value of getting out of urban environments and into nature. “There aren’t a lot of opportunities like this that are so close that you can be immersed in nature and a special environment like a wetland,” she said.

The land trust acquired the property through a deed transfer from a charitable trust established by developer Collins Haynes and Audubon Arkansas in 2011. The county assessor removed a tax lien against the charitable trust because the property’s deed restricted it from being used for commercial purposes. That action reduced the land’s monetary value to virtually nothing.

In 2003, Haynes bought 289 acres from the city for $5.2 million, which included the 121 acres of the preserve. Audubon Arkansas originally was going to manage the site, Lane said.

Much of the land to the south was developed into housing and car dealerships. Land to the northwest became a Sam’s Club in 2006.

Fran Alexander was among some local activists who tried to get the city to preserve the entire acreage before the 2003 sale. It proved difficult because of politics and competing interests at the time, she said.

Alexander said most people who drive by a wetland are likely to think of it as a weed patch or swamp. It can be a hard sell to galvanize support to preserve a wetland, as opposed to a mountain with hiking and biking trails, she said.

The most extensive areas of wetland in Arkansas lie along major rivers, according to the Association of State Wetland Managers, a national nonprofit group that promotes and enhances protection and management of wetland resources. The Bill Clark Presidential Park Wetlands in downtown Little Rock is one example. That wetland area consists of 13 acres along the Arkansas River near the Clinton Presidential Center.

Wetland is scattered throughout the state and is also associated with springs and seeps in areas like the Ouachita Mountains and the Ozarks.

Fayetteville has two other wetland areas. The World Peace wetland prairie consists of about 2½ acres, and the Woolsey wet prairie is a 44-acre restoration project that adjoins the city’s Westside Wastewater Treatment Facility.

Aside from providing crucial habitat for wildlife, wetland serves as a natural filtration system for stormwater. It removes pollutants before they reach the waterways. The Wilson Springs wetland enters Clabber Creek, which is a tributary of the Illinois River, Lane said.

Urban runoff flows right into Wilson Springs. The land trust has a mailing list of nearby homeowners so it can instruct them about ways to keep from harming the wetland preserve. The group recommends less use of pesticides and fertilizers, installation of rain gardens, and keeping drainage areas clear of vegetation and leaves.

The land trust will continually monitor Wilson Springs’ water quality and flora and fauna, in addition to providing general upkeep and maintenance, Lane said.

Visitors to the Wilson Springs preserve can walk the mowed trails on the northern end of the property, take pictures and just observe the wildlife. Doing much more than that would have a detrimental effect, Lane said. Dogs aren’t allowed in the preserve because of the danger of encounters with wild animals, she said.

It’s hoped that visitors will serve as stewards of the property, Lane said.

“When you first start getting onto the property, you can hear the highway,” she said. “But as you get in a little bit, that all melts away, and you really do feel immersed in nature. And that’s what we want people to have access to.”