It may seem like an ordinary Monday to anyone passing by the Richard Sheppard Arnold United States Courthouse in downtown Little Rock today.

But for those inside, it's a day that marks the end of an era.

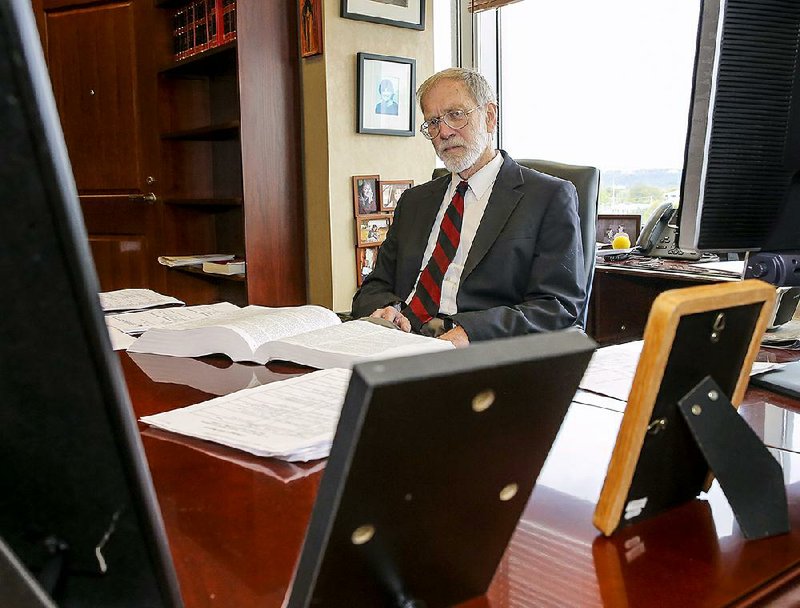

It's an era that officially began in July 2004, when Leon Holmes, then a 53-year-old attorney from Little Rock, was confirmed by the U.S. Senate as the newest U.S. district judge for the Eastern District of Arkansas. President George W. Bush had nominated him to the lifetime appointment 18 months earlier, but bickering in Congress helped slow the confirmation process to a crawl, at times making Holmes wonder if he should withdraw.

Fifteen years later, as he prepares to serve his final day as a federal judge before retiring, Holmes says he's glad he didn't withdraw.

If the silent tribute that played out Thursday in his fourth-floor courtroom is any indication, a lot of others are also glad he stayed put.

Holmes was presiding over his final hearing, a routine criminal sentencing, when a steady stream of attorneys, officials and courthouse employees quietly shuffled in and filled every bench and every inch of standing room. One observer said Holmes expertly masked his surprise, maintaining his "game face" throughout the proceeding, and once it was completed, calmly announced that he would return momentarily, before retreating into his chambers.

When Holmes re-emerged, it was to a standing ovation.

"It was emotional," U.S. District Clerk Jim McCormack recalled later in the day when asked about the unannounced event. He said the gathering of faces familiar to Holmes from the U.S. attorney's office, the federal public defender's office, the U.S. probation office, the U.S. Marshals Service and the clerk's office, as well as several private attorneys, was "a silent tribute and farewell, and a demonstration of the respect that all of us have for Judge Holmes."

The wordless, dignified nature of the tribute, McCormack said, "was symbolic of the reserved, quiet leadership Judge Holmes has shown over the last 15 years. I think Judge Holmes appreciated the spirit in which it was intended. We felt the message was received."

Also Thursday, at the monthly judges' meeting, Holmes' fellow judges presented him with a resolution: "The court thanks U.S. District Judge J. Leon Holmes for his more than 15 years of faithful service to the people of the United States of America and the rule of law."

"Judge Holmes will be greatly missed," Chief U.S. District Judge D. Price Marshall Jr. said later on behalf of the district's other six district judges and five magistrate judges. "He exemplifies in word and deed a judge as faithful servant of the law."

Marshall talked about the calm that has surrounded Holmes' work and "the quiet strength he exudes," noting, "The disputes that come through our doors need that."

"There are no small cases in Judge Holmes' mind," Marshall said. "They are all equally important, and he gives them all equal attention and comes up with the fairest answer under the law. He is a particularly good listener, which is a very important quality for being a judge."

FAMILY MATTERS

In an interview Wednesday in his chambers, Holmes revealed "one of the large factors" behind his decision to retire from judicial service at age 68.

"I have 17 grandchildren," he said, "including one yet to be born later this year. And all live out of state."

While Holmes' wife, Susan, has been free to attend family events in Arkansas and the four other states where their grandchildren live, Holmes said he doesn't want his official duties to keep him from participating any longer.

"I want to be able to have a relationship with my grandchildren," he said.

Holmes' retirement, like many aspects of his life, was well-planned, so it won't leave the remaining judges to juggle an extra load.

On March 31, 2017, Holmes advised President Donald Trump that he planned to take "senior status," a form of semi-retirement, on March 31, 2018. The designation allows judges who are at least 65 and who have been on the bench 10 to 15 years to continue serving, but with a reduced caseload. Once on senior status, he stopped accepting new cases, correctly anticipating that it would take 12 to 18 months to "work down the caseload."

By Wednesday, only one criminal defendant and three civil cases remained on his docket. The defendant -- a recent arrest in a multi-defendant case that had otherwise closed -- was the one being sentenced Thursday when the silent tribute began. The civil cases weren't ready for final adjudication yet, so they will be reassigned.

Asked if he will miss the job, Holmes said, "I'll miss the relationships with the people," referring to his secretary, courtroom deputy and law clerks, as well as his friendships with the other judges and employees of the clerk's office. Despite their varying places on the political spectrum, Holmes called the group of judges "very collegial."

Before becoming a judge, Holmes dealt strictly with civil law. But his judicial docket also included criminal cases, including the high-profile 2014 bribery and extortion trial of former state Treasurer Martha Shoffner, whom he later sentenced to 2½ years in prison.

Holmes became known for his soft-spoken manner, through which he gave everyone -- the accused, the accusers and victims alike -- the opportunity to be heard at length.

He said he liked the "more personal" nature of criminal cases, which were "eye-opening" to him, but he also enjoyed the challenge of civil cases that involved a lot of studying and analyzing the law. He said he couldn't classify either type of case as a favorite, since both are "so very different."

The trial that most stands out in his mind is a six-week non-jury trial that began in September 2010 as a result of a lawsuit the U.S. Department of Justice filed against the state over the care of residents of the Conway Human Development Center. The case was so complex and lengthy that Holmes presided over sessions on two Saturdays and a holiday.

The department alleged that the state had fallen below federal standards of care and was violating the civil rights of residents by favoring institutionalization of developmentally disabled adults and children, instead of helping them live in the least restrictive environment possible. The state, and many parents and guardians of the residents, countered that the residents were well cared-for and said they feared the lawsuit would cause the center to close its doors, leaving their loved ones without a safe place to live.

Eight months after testimony ended, Holmes issued his longest ruling ever, based on the testimony and subsequent voluminous post-trial filings. In the 85-page opinion, he ruled in favor of the state, saying the Justice Department failed to prove that the center violated the rights of its roughly 500 residents. The state hailed the ruling as "a huge victory."

WIT AND WISDOM

But despite the weighty matters that came before him, Holmes also demonstrated his witty side on occasion, such as his remarks when he closed a third week of testimony in the Conway case.

He solemnly told the attorneys, "I wanted to see if I'm understanding what you presented this week correctly," then read aloud from his notes, using the acronym-heavy language that the parties had been using prolifically.

"CHDC is an ICFMR, not an LEA, regulated by CMS, DDS and ADE, required to provide FAPE in the LRE," he began. By the time he was finished, attorneys and spectators throughout the courtroom were laughing.

Three years ago, in recusing from a civil case because of family ties that created a potential conflict of interest, Holmes wrote a three-page tongue-in-cheek recusal order explaining in excruciating detail the intricate connections linking his wife's grandmother to the plaintiff's grandmother.

He described how the focus of the lawsuit -- the mystery of how two teenage boys ended up on Saline County railroad tracks in 1987 -- was a regular topic of family reunions. He ended by saying that to an average person on the street, "assuming this person is a Southerner who knows about family reunions," there "ain't no way" a judge in such a circumstance would be considered impartial.

In 2005, just a few months after Holmes took the bench for the first time, he was named the chief U.S. district judge -- a seven-year mostly administrative position that follows a routine rotation based on age and seniority.

"For me, it was an awkward position," Holmes recalled Wednesday, "so I went around to all the judges and asked them for advice."

He said U.S. District Judge George Howard, who would die nearly three years later, told him that when he went off to the Navy, a particularly daunting endeavor as a young black man who had gone to segregated schools, he read Psalms 23 and 91 every day as reassurance of the Lord's protection.

Holmes, who would later move into the fourth-floor chambers that Howard had reserved in a new addition to the courthouse, said he has done the same ever since, and believes it has guided him through all his days as a judge.

He pointed to a wall of his chambers where a framed photograph of Howard and a framed copy of Psalm 91, both from Howard's funeral service, still remained hanging as of Wednesday.

"I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress; My God, in Him will I trust," the Scripture reads. "Surely He shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, He shall cover thee with His feathers, and under His wings shalt thou trust. .... Thou shalt not be afraid."

As for what else lies in his future -- another job, perhaps? -- Holmes said only, "I will leave it to the Lord to address me."

Metro on 09/30/2019