You lose a tennis match once a week for years to a guy, and you get to know him.

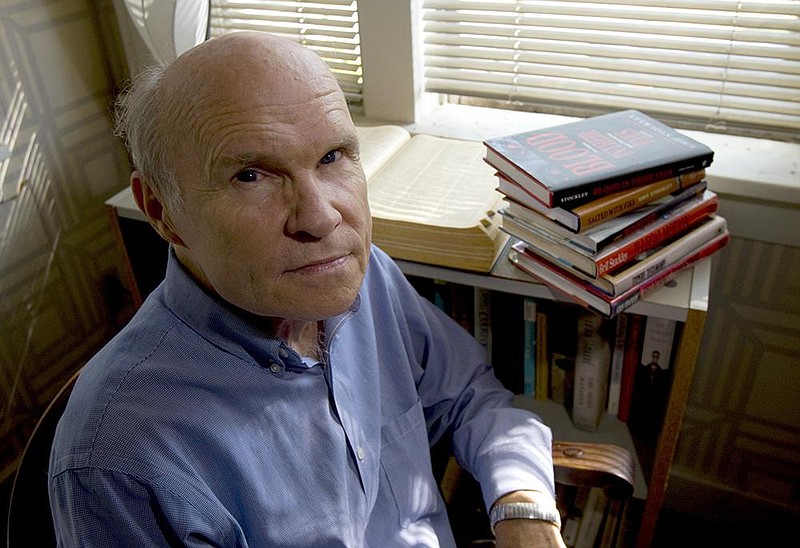

That's how I can tell you that Grif Stockley is focused, tenacious, purposeful and mentally tough. And it's how I can tell you that no one is perfect and that Grif might be a tad self-absorbed.

It's been 20 years since that fleetingly glorious but ultimately nightmarish weekday afternoon at the public tennis center in Little Rock. I led Grif by 5-0 in the third and deciding set of our weekly tennis battle. He'd won several hundred of these matches to my half-dozen.

About 45 minutes later, I sat beside Grif on the courtside bench. Sweat poured off me and rage boiled inside. Nothing was spoken, but everything was understood.

I said, "You do know this is the last time we ever play."

He said, "Yeah."

He'd won the set, 7-6, and match.

I hung my head and drug my feet to the car, hating and loving that focused and purposeful little sonofa ... gun. And myself.

Grif's broader purpose was to practice nonprofit law in behalf of the underprivileged, which he did for a modest living for decades. With the Center for Arkansas Legal Services, he participated in seminal cases that reached the Arkansas Supreme Court and reformed primitive services for children and the mentally ill.

His broader purpose also came to be wrestling with his white privilege from the glory Delta days in his native Marianna amid the racism that engulfed his formative years in the '50s and '60s.

There's another thing he did. Relatively late in life, he decided to become an author.

He wrote a series of lawyer novels featuring a character called Gideon Page who was a good man with issues and a daughter he lived for. He was rather like Grif Stockley.

Then he turned to nonfiction, to Arkansas' race history, and produced important works including a book about the Elaine race massacre and a biography of Daisy Bates.

He was not a scholar. He was not a gifted writer. He simply was focused, tenacious, purposeful and successful.

He would hit loopy defensive groundstrokes until you came to the net on him. Then he'd suddenly produce a directional shot with pace. That's a metaphor as well as an infuriating blankety-blank fact.

Grif now is beset by damnable cognitive decline, a disclosure made here by his and his nearest loved ones' permission. He's somewhere between functioning and not. He can leave a clear voice mail, but he'll want to know why you're calling when you return the call. He can competently send an email inviting you to provide a blurb for his forthcoming memoir. Then you learn that the book is long finished and due out soon and notably abundant in glowing blurbs already.

Janis Kearney, diarist for President Clinton, writes in her cover endorsement that Grif's memoir "paid witness to southerner-ness from a perspective of humanity rather than his whiteness." Guy Lancaster, editor of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, says in his that the book provides "a map from our perennial state of despair to a state that I would dare call enlightenment."

The important thing is that Grif got this chatty, funny, honest, meditative and compelling memoir written ahead of that decline, and now self-published with help.

It's the lightest and best writing of Grif's career, and it's called "Hypo-

grif in Bubbaville: A Memoir of Race, Class and Ego."

The book is the story of the iconoclastic 70-plus years lived by a scrawny, balding, drawling guy from the Delta who spent his life absorbing his place and determining to understand, explain, lament and challenge it.

And it's a work in which Grif accepts that an honest accounting requires that he devote thoughts to his own ego, arising from being "spoiled rotten," as he puts it, by sisters from his beginning. He came to understand he wasn't nearly as wonderful as he'd been led as a child to believe. But I wouldn't say he ever put aside entirely the defining formative message that he warranted a little pampering.

He writes of coming to understand in adolescence and young adulthood that his growing-up bliss of the '50s and '60s came from the lies that white people told themselves.

He surprised and then disappointed himself by getting invited to and accepting a fraternity offer at Southwestern of Memphis. He was not a frat boy. But he wasn't yet able to decline the invitation to play out the charade that he was.

I had not known until reading the book that he played on the Division 3 non-scholarship tennis team, surely driving mad more than one hard-hitting opponent. He writes that the coach told him he'd teach him to serve and volley, except that he'd inevitably outrun the serve to the net, and get hit in the back of the head by his own ball.

I knew he'd joined the Peace Corps, but not that he'd gone to the northern coast of Colombia.

There was so much we could have talked about while I was working so hard week after week to lose tennis matches, and walking huffily away when it happened.

Now I have the book, available to others interested in an important tale of our time and place. I only wish that Grif and I could play another tennis match and I could take the time during changeovers to ... I don't know ... talk to him, mine his experiences, grow.

Grif and his book span the Delta as a place of white-flourishing and then white-abandonment. It spans Orval Faubus' disgrace, JFK's inspiration, LBJ's Great Society, the civil rights movement of the '60s, the Vietnam War, and a race chasm that is now newly revealed in our streets--closing only in a few places while widening and steepening in others.

It's a book rich in anecdotes. The one I keep thinking about is of Grif's friendship with a couple of fellow law-school students who were Black, and of his internship in 1970 at the state's pioneering civil rights firm headed by John Walker, Phil Kaplan, Jack Lavey, Buddy Rotenberry and Les Hollings-worth.

He joined those Black law-school friends at a Black bar on Ninth Street in Little Rock on a Friday night, but was asked to leave on the lie that the crowd actually was a private party. And he left, finding the experience less unjust or ironic than simply hurtful to his feelings and an interesting turnabout that made him wonder what we still wonder, which is whether we can ever get along.

Grif had been intending that night to accompany those Black friends to an interns' party afterward at John Walker's home. He ended up not going. He writes that Walker asked him about his absence and that he explained what had happened to him at the bar on the way to the party. He writes that Walker seemed wholly unsympathetic.

He writes that, decades later, Walker said as an aside in a speech at the Clinton School that he hadn't believed him because he knew he was from Marianna.

Distrust during our time by place and color, revealed in the minor and counter-intuitive experience of a white-privileged Delta son venturing introspectively and purposely into the chasm ... that's one way that Grif's memoir is a worthy take on the Arkansas 20th-century story.

John Brummett is a member of the Arkansas Writers' Hall of Fame.

jbrummett@adgnewsroom.com