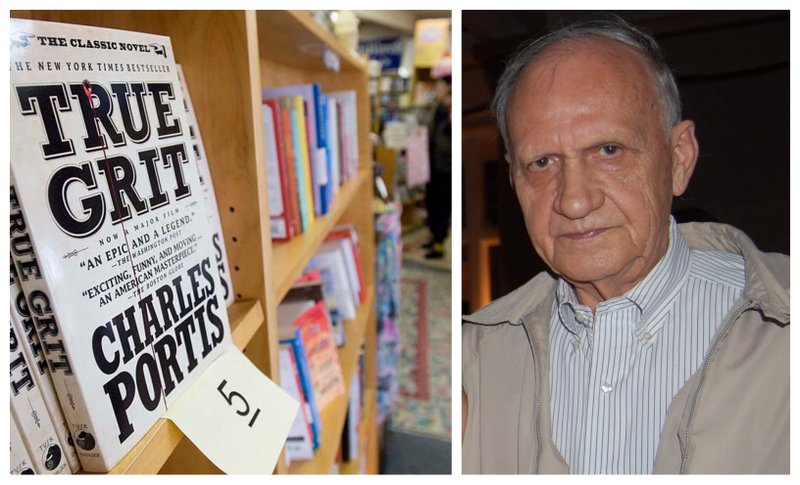

Charles McColl Portis, an Arkansas native best known for his depiction of a one-eyed U.S. marshal named Rooster Cogburn in the 1968 novel True Grit, died Monday at a Little Rock hospice.

He was 86.

Portis was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and dementia in 2012 and died of complications from the illness, said his brother Jonathan Portis.

Charles Portis, whose literary voice was distinctive for its deadpan humor and attention to odd details, published five novels -- Norwood (1966), True Grit (1968), The Dog of the South (1979), Masters of Atlantis (1985) and Gringos (1991) -- and the nonfiction collection Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany (2012).

True Grit is the story of the fictional 14-year-old Mattie Ross from Yell County, Ark., who recruits Cogburn to avenge the murder of her father. The book was made into a 1969 movie of the same name, starring John Wayne, Kim Darby and Arkansas native Glen Campbell. A remake of the film starring Hailee Steinfeld and Jeff Bridges was directed and produced by Ethan and Joel Coen and executive-produced by Steven Spielberg in 2010.

In 1970, Portis' first novel, Norwood -- which follows the cross-country trip of a young ex-Marine living in Texas -- was adapted into a movie, starring Campbell, Darby and football-player-turned-actor Joe Namath.

Portis -- who was known as either "Buddy" or "Charlie" depending on which part of his life someone came to know him -- was uncomfortable with the fame that resulted from his literary success. He rarely granted interviews, balked at being photographed and lived quietly in an apartment in Little Rock's Riverdale area.

"He had this great amount of success with True Grit. I think it didn't sit well with him," said Jonathan Portis. "He didn't like to attract attention. He was comfortable around his friends, but shy around strangers. He preferred to go as an unknown person because he was a people watcher. He would hear snatches of conversations or see people who had a particular look and he would take note of that. You'd see them in his books."

Carlo Rotella, a journalist and a professor of American studies at Boston College, has written extensively about Portis and his work. After a 2010 visit in a Little Rock bar, Rotella wrote that Portis seemed ill at ease, but he wasn't "trying to affect a reclusive literary persona." Rather, "he seems to have the old-fashioned notion that he said what he had to say on the page."

In a recent email conversation, Rotella said Portis' aversion to self-promotion was typical of the characters he created.

"On the one hand they want to do momentous things and on the other hand they worry that in doing those things they might make themselves ridiculous," Rotella said. "He seemed to me like a guy who didn't want to give the impression that he thought of himself as a Big-Deal Writer."

Longtime friend Rick Cobb, who met Portis more than two decades ago when he was having a beer at the Faded Rose, a Little Rock restaurant and bar in Portis' neighborhood, said Portis rarely initiated conversations.

"He had to warm up to you a little before he spoke," Cobb said.

Then the stories would pour out.

The tales told during the daily bar visits or at meals at the Waffle House or the Dixie Cafe with his friends were not elaborate or exaggerated. They were like Portis' novels -- straightforward, and rich with detail and dry humor.

"I had already read his books before I ever met him. We hardly ever discussed that part of his life," Cobb said. "I knew he did it, and he knew he did it and that was that."

His longtime friend and journalism colleague William Whitworth -- who would later become an editor at The New Yorker and then editor-in-chief at The Atlantic -- said that while Portis was known for avoiding the spotlight, he was not a hermit or anti-social.

"In fact, he was the life of the party. He liked hanging out with his friends and was a lively presence in any gathering," Whitworth said. "When he was a reporter at the New York Herald Tribune in the '60s, you could often find him telling funny stories at the Trib staff's favorite bar, Artist and Writers Restaurant [known as Bleeck's, after its owner]. In those days he was often out with Nora Ephron, who -- years away from becoming a successful Hollywood director -- was then a reporter at the New York Post."

EL DORADO ROOTS

Portis was born on Dec. 28, 1933, in El Dorado. His father, the late Samuel Portis, had followed his brother in the mid-1920s from southern Alabama to Smackover during the oil boom. It was there that he met and married Alice Waddell.

Samuel Portis went from teaching English and history in Norphlet to retiring in the 1970s as superintendent of the Hamburg School District. Alice Portis was a prolific author in her own right. She wrote stories and sold office supplies at the weekly Hamburg newspaper, as well as wrote feature stories through the years for the Arkansas Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat.

"She had this big Underwood typewriter she was always pounding away at," said Jonathan Portis, who began work as a copy editor at the Arkansas Gazette in 1972 and had stints as the newspaper's assistant city editor, state editor and business editor before the newspaper's assets were purchased by the Democrat in 1991.

Portis' brother, Dr. Richard Portis, also worked at the Gazette as a state desk reporter, then as a copy editor, in the mid-1960s before going to medical school.

Charles Portis spent his childhood in El Dorado, Norphlet and Mount Holly before graduating from Hamburg High School. He enlisted in the Marines and fought in the Korean War. It was during that time that Jonathan Portis believes his brother started writing.

"He became a voracious reader. He read everything he could get his hands on," Jonathan Portis said. "I think he decided, 'I might try my hand at this.'"

Whitworth called Portis a "closet intellectual."

"When we were editing one of his contributions to The Atlantic," Whitworth recalled, "I received a note from Portis that said, 'Yes, there are some things that need changing or deleting in that travel piece. The John Ruskin allusion was reaching a bit. ... I was taking a swipe at the English school of travel writing, which is largely about architecture. Cornice descriptions, at great length. Ruskin started all that, but he was a genius and carries us along.'"

Ruskin was a Victorian-era art critic.

NEWSPAPER CAREER

Portis graduated from the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville in 1958 with a bachelor's degree in journalism. In a 2001 interview with journalist Roy Reed for the Arkansas Gazette Project, Portis described driving to Fayetteville with his friend Billy Rodgers and showing up with "a high school diploma and $50" to register.

"You had to choose a major, so I put down journalism," Portis said in the interview. "I must have thought it would be fun and not very hard, something like barber college. Not to offend the barbers. They probably provide a more useful service."

Portis' journalism career took him from his first job at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis to two years -- 1959-60 -- at the Arkansas Gazette, where he wrote the column "Our Town," and eventually to London as bureau chief for the New York Herald Tribune.

Whitworth remembers Portis at the Arkansas Gazette, "sitting there behind me all day, smoking and staring at his great old Underwood as he labored over his 'Our Town' column."

"I say that Portis was a comic genius and one of the best American writers of the second half of the 20th century," Whitworth said.

In the interview with Reed, Portis said he thought he could do the column well, but he could never "get into a stride."

"Clumsy, half-baked stuff. It was a grind," Portis said. "I had to do five of those things each week, plus a long Sunday piece -- an expanded feature story with pictures. And when you find yourself trying to fill space, you're in trouble."

Portis recalled a Sunday piece on a "big cockfighting meet in Garland County."

"Pat Carithers and I drove down there," Portis said. "All these high-rollers in dusty Cadillacs with Texas and Louisiana plates with their fighting chickens and flashing their thick wads of cash."

Whitworth said Portis had a wonderful eye.

"His writing was never abstract. It was concrete," Whitworth said. "If a character of his was driving down the highway or riding a Greyhound bus or changing a tire, you were right there with him. Portis didn't tell jokes -- he noticed things. I believe that a big part of what made his writing funny was that his people and places were so wonderfully observed. He was almost as detail-oriented as Nabokov."

Vladimir Nabokov was a Russian-born novelist and critic.

Rotella said the most beloved qualities of Portis' writing -- his way with language, his sensibility -- are "nearly impossible to imitate or even define" but they resonate with all kinds of people.

"I'll put it this way: When my 9-year-old daughter turned over a straight that beat my two pair and said, 'Shot by a child!' I knew that reading True Grit to my kids had been a good idea," Rotella said.

Ian Frazier -- a staff writer for The New Yorker and author of numerous books, including Great Plains, Travels in Siberia, and On the Rez -- said what he admired most about Portis was how his humor could be funny and serious at the same time.

"When Mattie Ross regrets that because of her absence, her father's funeral service was preached by a man she describes as 'a wool-hatted crank,' the epithet is hilarious, but Mattie's sadness is real," Frazier said. "Portis wrote the funniest works of great American literature since [Mark] Twain."

TRUE GRIT

Jonathan Portis said the family was shocked when Portis wrote a letter to his parents to say he was moving back to Arkansas from London. While living in New York, he had met Lynn Nesbit, who had just started out as a literary agent. Portis showed her portions of Norwood.

"She said, 'If you can finish this, I can get it published.' So he took her at her word," Jonathan Portis said. "At some point he said to himself, 'If I'm ever going to do this, I'd better do it now."

In 1964, he gave up journalism, moved to a cabin on Lake Norphlet and finished Norwood -- much to the envy of the late author and journalist Tom Wolfe, who worked with Portis at the New York Herald Tribune in the 1960s.

"He made a fortune. ... A fishing shack! In Arkansas! It was too godd***ed perfect to be true, and yet there it was," Wolfe is quoted as saying in New York magazine.

Wolfe said in an email before his May 14, 2018, death, that Portis ranks with the great comic novelists, such as Twain, Louis-Ferdinand Celine, Nikolai Gogol and Evelyn Waugh.

Jonathan Portis said that after Norwood was published, Portis moved to Los Angeles and briefly did some script doctoring for some television shows.

"He didn't particularly like it, and he came back to Hamburg," Jonathan Portis said.

"We didn't know what he was going to do next. Was he going to continue this novelist career or become a teacher or go back to newspaper work?" Jonathan Portis said. "He told us he was working on a novel about the 19th century, but he never talked about it. He always said 'If you talk about it, you don't do it.' Then suddenly True Grit came out."

HIS LEGACY

The American humorist Roy Blount Jr., author of more than 20 books and a frequent contributor to magazines, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic and Vanity Fair, said Portis' legacy will last generations.

"I believe Charles Portis will still be funny to my great-great-grandchildren," Blount said. "And they will be able to say, 'My great-great-granddaddy knew him.'"

Nothing much changed in Portis' life because of his literary success, Jonathan Portis said. Charles Portis bought his parents a house in Little Rock, but Portis lived in a hotel one year and a trailer another before finally settling into an apartment in Little Rock. After his father died in 1984, Portis moved his mother to a neighboring apartment so he could keep a closer eye on her.

"He didn't live any kind of wild and crazy life. He was careful with his money," Jonathan Portis said. "He was still the same person."

And he still used his old manual Underwood typewriter, his friend Cobb said.

"He would go to yard sales and look for used typewriters just to find parts to keep it up and going," Cobb said.

Portis would spend several months out of the year in San Miguel de Allende in central Mexico. He bought a 1973 Chevrolet Blazer, one of the early four-wheel-drive models, and drove through the interior of Mexico.

"He liked the people," Jonathan Portis said. "When he would get ready to go to Mexico, he would call me and say, 'If you have any old clothes or towels, give them to me because I'll give them out in Mexico.'"

Portis rescued an abandoned puppy on one of his trips through Tijuana, found a taxi driver to smuggle the dog over the border and took it to a vet.

"He drove back across the country with this little bitty dog. He named him Shorty," Jonathan Portis said. "It quickly became apparent to him that he lived in an apartment and was always on the move, so a dog wasn't a good fit for him. He gave the dog to our parents and built a fence around their yard."

In his last days, numerous friends and family members visited Portis, who never married or had children.

"It was surreal at first when I met him so many years ago," Cobb said, "but he just became a regular guy."

Information for this article was contributed by Ginny Monk of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Metro on 02/18/2020