They told us Dad's brain arrived at Boston University in a matter of hours after he died.

That surprised me. Not that it happened--Mother had signed the papers months before--but that it happened so quickly. It was the beginning of an impressive process with a surprising report waiting at the end.

I credit my mother with the decision to donate my dad's brain to the Boston University CTE Center led by Dr. Ann McKee. If you have seen any of the documentaries on concussions and football, particularly the PBS Frontline presentation League of Denial, you know she is the world's leading research expert on CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy).

CTE is a degenerative brain disease research shows is caused by repetitive brain trauma. That repeated brain trauma triggers progressive degeneration of the brain tissue, including the build-up of an abnormal protein called tau. At this point, it can only be diagnosed after death.

In 2017, my mother saw a report on a study at BU where researchers were especially interested in looking at brains from former NFL players. My dad played four seasons in the NFL. At the time, he was in the later stages of a tough battle with dementia. After a family meeting, we decided to enroll him in the program.

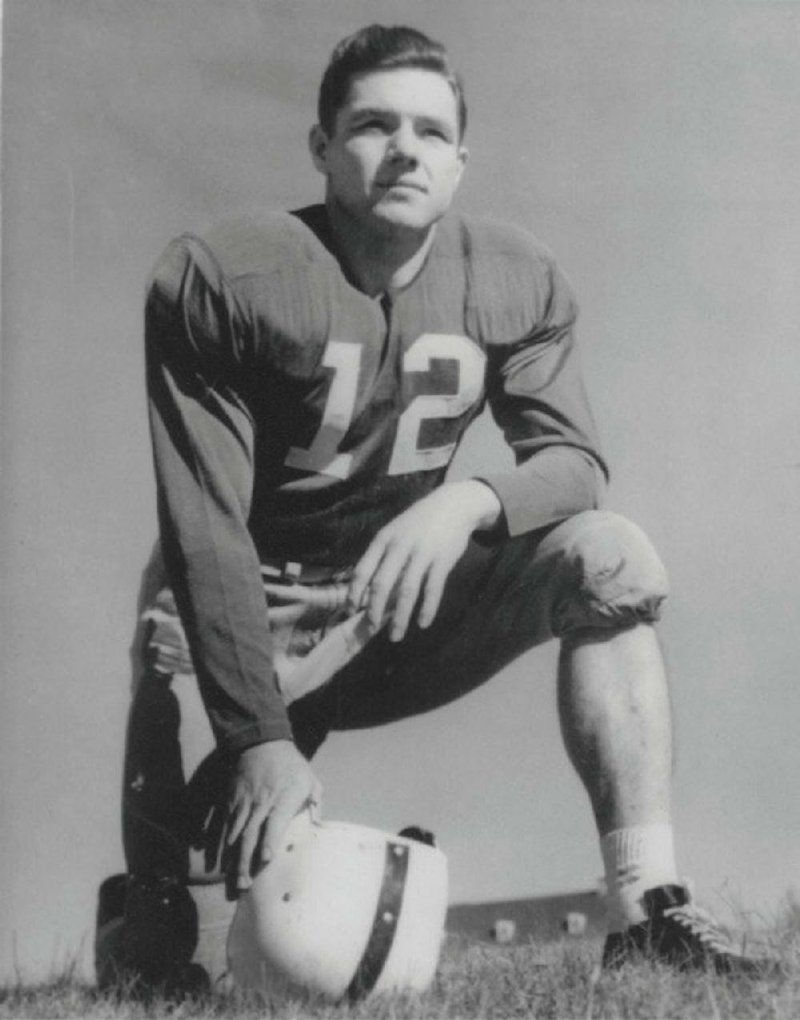

Arkansans are more familiar with the football Dad played at the University of Arkansas where he was a three-time All Southwest Conference Team member and a 1948 All-American. In the summer prior to his senior year, he tied a world record in the 110 meter high hurdles at the NCAA Track and Field Championships and won a Silver Medal in London at the 1948 Summer Olympics.

Dad was considered by many to be one of if not the greatest all-around athlete to come out of Arkansas in the 20th century. Anyone familiar with Arkansas sports history will know I am talking about Clyde "Smackover" Scott.

The actual process of the study on my father's brain was interesting. The researchers were divided into two groups. One group gathered extensive information from the family through three very thorough interviews. They wanted to know what sports Dad played, how long he participated, his family's medical history and so forth. That group then used the information to predict the likelihood of Dad having CTE damage.

The second group then analyzed the actual brain tissue and determined the results. One of the goals of the study is to come up with criteria that will enable researchers to accurately predict the presence of CTE damage before death. That would help them evaluate potential treatments and therapies. I don't know what their prediction was for Dad, but I know the results.

The study rates the extent of CTE damage on a scale of 1-4 with stage 4 designating the most severe case. The researcher who called reported that Dad rated a high 4. He said they found extensive signs of CTE throughout his brain. He also said his brain had shrunken considerably.

That report was hard to hear. Football helped bring my dad out of poverty, provided a wonderful education, gave him a financial boost out of college and helped kick-start a successful business career. He loved the game, his teammates, his experiences and his fans. I doubt he would have changed anything even if he had known what was coming, but he clearly paid a price. The last years of his life were difficult.

Dad died at the age of 93. His long battle with dementia started in his mid-80s. Even though he lived a long life, the findings tell us the game he loved likely took away some quality years. There is no family history of dementia. His mother died at 102 and his dad died of emphysema at 94. Both were mentally sharp at the end.

The knowledge that football may well have affected the quality of my dad's life brings up an uncomfortable question. Even though I inherited none of my dad's ability (as my junior high coach can attest), I enjoy watching football and cheering for my teams. I have always loved the game. That is true for almost everyone I know. When I get with my friends in the fall, it is what we talk about. Football has always been much more than a sport to me.

But now a troubling thought keeps coming up: What price is being paid for my entertainment?

There have been 800-plus brains donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank at Boston University since 2008. Each one comes with a story. Many of the stories can be found on the Concussion Legacy Foundation website. You will see that Dad is not the only famous Arkansas football star in the program.

You will also see some of the donated brains came from high school players. Symptoms generally take years to appear, but CTE has been seen in people as young as 17. You can feel the parents' anguish as they tell their stories. It is a difficult read.

We are seeing an epic collision happening in slow motion. The scientific findings from studies, such as the October 2019 one published in the Annals of Neurology led by Boston University researchers that found the risk for developing CTE increases 30 percent per year of tackle football played, are crashing into America's favorite sport and a multibillion-dollar industry.

Changes are being made, but will they be enough? How will parents of young boys react as more is known? When will the lawyers get more involved? What will the sport look like in the future and who will play it? Questions are piling up, and answers are hard to get.

Science is presenting us with another inconvenient truth we will have to come to terms with. It is going to be a very difficult process that will likely take years to sort out. I expect I will continue to put on my red, watch football, and cheer for my team.

But it won't feel like it used to. That is sad.

Steve Scott of Maumelle is an agricultural marketing consultant.

Editorial on 02/23/2020