"David Brooks just wrote a book called The Second Mountain [: The Quest for a Moral Life]," says Frank Sharp, standing in a hallway of the Ozark Mountain Smokehouse building on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in Fayetteville, a structure that he built for his family business in 1976. Sharp is 81, though you would never guess it. His fitness and speed as he tours the huge building and his memory as he speaks of the past seem that of a spry 50-year-old. "The first mountain is: You get your education, you've had a job, you're up here" -- he pauses to indicate a career high with his hand -- "and then you say, 'Is this really what I want to do? Where I want to be?' And so then the second mountain is where you're doing community outreach."

Sharp offers this book recommendation to a friend -- an employee of the Northwest Arkansas Land Trust that is housed in the Smokehouse, rent free, courtesy of Sharp's philanthropy -- but given the trajectory of Sharp's life since he sold his business in 2006, surely he recognizes himself in Brooks' book. Sharp is, without question, on his second mountain -- and seemingly loving every moment of it.

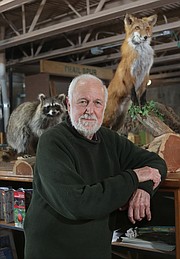

Self Portrait

Frank Sharp

My greatest fear is that northwest Arkansas, with its explosive growth, will become an urban sprawl and lose its sense of place: its natural areas, small family farms, compact downtowns and neighborliness.

The people who had the most impact on my life were my parents, Roy and Mary Sharp, who had the nerve to buy a rocky mountain farm during the Second World War and taught me to work hard, be frugal and enjoy life. Evangeline Archer, early on in the effort to save the Buffalo River, introduced me to the importance of preserving the environment. My wife, Sara, who I met at a church convention in our teens and to whom I’ve been married for almost sixty years, has — unfortunately — the most retentive mind I’ve ever encountered. My adult children have inherited their grandparents’ hospitality gene, my energy and their mother’s smarts.

The best business decision I ever made was to stay in northwest Arkansas.

The one word to sum me up is still hillbilly.

Next Week

Dr. Jerad Gardner

Little Rock

The Smokehouse

Sharp's history and the history of the Ozark Mountain Smokehouse are nearly Ozark folklore: Roy and Mary Sharp moved to Fayetteville from Texas in the 1940s, bought acreage on Kessler Mountain -- land that stretches up beyond the Smokehouse building -- and set out, successfully, to farm and raise their two children.

"We had cattle and hogs and geese and turkeys and ducks and chickens," Sharp recites. "We sold cream and eggs in town."

The seed of the business that would become the Ozark Mountain Smokehouse was planted when Sharp's father had a smoked turkey sandwich at a gathering in Texas. The taste intrigued him, though he thought it could be improved upon. He consulted with a neighbor who smoked meats and, with some experimentation, perfected the practice, but not before burning down a barn in the process. (The livestock were saved, but the structure was a total loss.) For years, Ozark Mountain Smokehouse existed as, primarily, a mail-order business that provided smoked meats for Christmas -- almost as a hobby for his father, says Sharp. Though Sharp graduated from college with a degree in chemical engineering, he returned home to try and turn the business into something that could support his wife, Sara, and their four children. By the late 1960s, Sharp had managed to do just that. He opened his first store near Winslow in 1969. Ultimately, Sharp would open 12 retail stores throughout the state, and his business would become wildly popular for its quality smoked meats, build-your-own-sandwich bars and homemade jams and jellies.

Community involvement and charitable giving were a part of Sharp's upbringing. His mother, a talented artist, taught art for years at the organization that would become the Elizabeth Richardson Center. His father delighted in entertaining and was known for throwing huge barbecues for his neighbors in the 1940s, when meat was a rare delicacy due to war rationing.

Perhaps it was his parents' modeling that led Sharp to be active in the community: He reckons that his first experience with "rabble rousing" was when he teamed up with the University of Arkansas' Cyrus Sutherland to get the Fayetteville square's old post office designated a national historic building, thereby saving it from demolition in the late 1970s. He served on Fayetteville's City Board of Directors and was one of the primary movers and shakers responsible for building the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville. For decades, he and Sara have offered up their own home to hold fundraisers for various nonprofits, with Sharp making gourmet pizzas for the crowd in the pizza ovens he added to the commercial-grade kitchen on their property. So to imply that Sharp did not reach his "second mountain" until after he sold his business in 2006 is not quite accurate. But, most certainly, it's during this period of his life when he's been able to pursue community philan-thropy and activism with a single-minded focus from which many area organiza-tions have benefited.

Take the Northwest Arkansas Land Trust, for example: This nonprofit's goal, says its website, "is to work collaboratively and tirelessly to ensure that our region's abundant scenic beauty, clean air, clean water, wildlife habitat, outdoor recreation opportunities, local food supply and natural heritage are permanently protected for the benefit and prosperity of current and future generations." Protecting the natural beauty of Northwest Arkansas is important to Sharp, and he's known the organization's executive director, Terri Lane, since she hung out with the Sharp kids as a child.

"Frank had been keeping tabs on what I was doing with the Land Trust and the growth of the organization," says Lane. "We were renting a very small office space on the other side of town and had only two staff at that time. Frank reached out and asked if I would be interested in moving the Land Trust offices to the Smokehouse, rent-free."

At the time, Sharp was renting 4,000 of the building's 18,000 square feet to the homegrown clothing company Fayettechill (which remains the only space in the building for which Sharp accepts rent). Lane's task was, she says, to "create more organization and upkeep," in exchange for the offices.

"The value of the contributed office and outreach space alone saves us over $13,000 in rent annually," notes Lane. In addition, Sharp continues to make improvements to the building that benefit the goals and mission of the organization as a teaching institution. Lane and her team cleared and outfitted a large space in the building to use as the Kessler Mountain Classroom and Nature Center, which hosts students from elementary school to college.

"Those poor [visiting] kids, they used to have to go upstairs and line up for two restrooms," says Sharp, proudly showing off two new restrooms he had installed where two huge ovens used to be, each with facilities for four people at a time.

Sharp also built pizza ovens in the outside area where students meet before heading up to the looping forest trail they hike on their visits out to Kessler Mountain.

"This came out of our Dickson Street smokehouse," he says, gesturing to the long, narrow food bar near the ovens. "It's where you used to build your own sandwich. Now you build your own pizza. They take the pizza dough, and then there's pizza sauce, bell peppers, mushrooms, tomatoes, pepperoni, salami, mozzarella ... we had an environmental science class from Fayetteville High School, about 70 students, and we fed them in about 45 minutes."

Lane says Sharp has invested more than $158,000 in improvements like that over the past five years. "The Land Trust has grown from two to eight staff since we moved our operations to the Smokehouse. We've had the space to expand here, and I can't think of a better location. Frank's in-kind donations are critical to the mission of the Land Trust. As a nonprofit conservation organization, it means that we can invest more on the important programs we provide and save more land."

The Community

Sharp's passion for conservation is well documented. Consider his involvement in the movement to protect as much land as possible on Kessler Mountain. In 2010, Chambers Bank donated 200 acres of land to the city of Fayetteville for the creation of Kessler Mountain Regional Park. When a proposed development of 800 acres for retail businesses and up to 4,000 housing units failed shortly after, Sharp saw an opportunity to secure even more land for public use. With the help of the Fayetteville Natural Heritage Association, he put together an 80-plus page full-color packet comprised of letters of support from area conservationists, geologists, environmentalists and outdoor enthusiasts to support the idea of the city protecting the land by purchasing part of the 800-acre parcel that was now up for grabs. He worked with the Ozark Off-Road Cyclists club to build additional biking and hiking trails. He hosted lectures by scientists who talked about their discoveries of the natural wonders that exist on the mountain -- discoveries like the one made by University of Arkansas professor of Geology David Stahle, who wrote in an email to Sharp, "... We found a nice pocket of uncut ancient forest. ...We cored one post oak (44cm DBH) and dated the inner ring to 1724."

Sharp's single-minded focus on the project was rewarded in 2014, when the city of Fayetteville -- with a matching grant from the Walton Family Foundation -- agreed to purchase over 350 acres of Mount Kessler land, almost tripling the size of the original planned park.

Greg Mitchell was the geographic information systems coordinator for the city of Fayetteville while Sharp was leading the charge for Kessler Mountain.

"Frank would come in and ask us to make maps for him to use at meetings with the city or other groups," Mitchell says. "He was so passionate, organized and hard-working -- a pleasure to work with in every way. ... He immediately impressed me with his good ideas, drive, determination and energy. There is little doubt in my mind that Kessler Mountain would not exist as a city park were it not for Frank. He doggedly pursued his vision by writing and talking to everyone who was in a position to help. I don't want to say he did it himself -- I'm sure there were others involved -- but he was the driving force behind it."

Mitchell is a perfect example of how Sharp generously shares resources when he can. Mitchell took a letterpress class in 2015 and fell in love with the art. When someone suggested he talk to Sharp about getting access to some printing equipment he had stored at his home, he was amazed to find that Sharp was in possession of hard-to-find gear that he had purchased to save money by printing his own materials when the Ozark Mountain Smokehouse was still a fledgling business.

"What I walked into in 2015 was a fully equipped letterpress shop, circa 1961," says Mitchell, who adds that it's rare for anyone to have these nearly antique presses on hand. "What makes it unusual today is that 99.9% of these shops ended up in the scrapyard. There are a few of these presses left in Northwest Arkansas -- ones at UAFS and JBU get regular use -- but they are few and far between. Frank's practical nature and now, sense of history, have preserved his shop for more generations to use and enjoy."

When Mitchell told Sharp about his interest in learning more about letterpress printing, Sharp surprised Mitchell by offering his little print shop as a resource.

"He was immediately welcoming, told me to come up any time and [said] he'd show me around," says Mitchell, now an artist whose business, "I am Here Cards", sells custom maps printed on Sharp's vintage printing presses. "After an initial visit, he gave me free access to the printshop -- literally free in that he wouldn't take a dime from me -- and access at any and all times. In addition, Frank insisted on paying for new rollers for both presses, about a $1,000 investment. I became a regular visitor and have been ever since. His help has certainly enabled me to move forward much more quickly -- and cheaply -- than I would have done on my own."

Sharp has also opened the doors at the Smokehouse to allow theater and music groups to perform there, free of charge. The Smokehouse Players, a theater troupe, has been performing in a space Sharp converted into a small theater in 2017.

"Frank is a very generous person, and he lets us use the 'Chillin' Room' for free," says Terry Vaughan, co-founder of the Smokehouse Players. "Producing theater -- even the bare-bones theater that we offer at the Smokehouse -- is very expensive, and we couldn't afford to do this if we had to pay to use the performance space."

Vaughan has taken Sharp's generosity and paid it forward into the community.

"Because of his kindness, we wanted to do something kind in return. We decided that Smokehouse Players would provide free theater to the Northwest Arkansas community while raising awareness about Magdalene Serenity House. All donations received on the opening night of each new show go directly to Magdalene. Our last production, "Night Mother' by Marsha Norman, raised almost $6,800 for MSH due to four matching donors coming forward for our benefit on opening night. All of this is only possible because of Frank's generosity."

"Frank embodies the spirit of Fayetteville, in my opinion," says Lane. "He and Sara have supported conservation and the arts for decades. Frank has been a critical community leader for many years -- as a business owner, landlord, elected official and in bringing people together to create the type of city and community we all want and love. He continues to shape our community with his energy, passion and vision. In a city and region that is growing so fast we risk losing 'who we are' in the process, Frank is establishing a legacy that helps ensure we don't."

When Sharp was inducted in the Fayetteville Public Education Foundation Hall of Honor in 2009, he didn't tout his own accomplishments when he accepted the award. Instead, he gave an emotional speech that recounted the Fayetteville Public Schools' history of racial integration in 1954, carefully listing the names of every school board member who voted for it, as well as the African-American students who were the first to attend the public school system. Ten years later, he still doesn't much care for talking about himself. He doesn't spend a whole lot of time considering, George Bailey-like, how different the landscape of Fayetteville would look had he not landed on Kessler Mountain so many years ago. When asked, point-blank, why he gives so much to the community, he looks almost quizzical, as though the question doesn't quite make sense. After a few beats, his answer is simple and succinct.

"Well," he says, "the community has done so much for me."

NAN Profiles on 01/19/2020