"She was born with her eyes open," says Raven Cook's mom, Patsy Warren-Cook. She's speaking literally, not metaphorically, although she acknowledges that her daughter's arrival into the world -- eyes wide, peering around the hospital room -- is an apt metaphor for where Cook finds herself now, three decades later. "I knew she was going to be something. I knew she was going to be deep in something."

Today, Cook's wide-open eyes are focused on filling in the gaps of American history -- the result of a public school system that tends to focus on Black history one lone month out of the school year and commonly limits the topics to slavery and the civil rights era. There is rarely acknowledgment of the full scope of the racial violence perpetrated against Black people -- consider that the massacres of Black communities like the ones in Tulsa, Okla., Wilmington, N.C., Rosewood and Ocoee, Fla., Slocum, Texas, Springfield, Ill., and Elaine, Ark., are rarely covered -- and little weaving of their accomplishments and contributions into the overall story of the country.

"I love talking to people about Black contributions because it's American history," says Cook. "It's so beautiful to think about how people who have constantly faced hell just continue to create and love and push and try and just have this hope. And to know I'm one of their descendants -- it's good work. It's good work."

Cook currently serves as a museum educator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, where she helps museumgoers connect to artwork with a perspective that might be new to them -- as in a presentation from last year, when she discussed "Black identity in America and the mobility of Black women throughout history through the lens of Winslow Homer's 'The Cotton Pickers'." This year, she started a weekly radio show on KUAF called "Reflections in Black" where she talks about notable figures like Stokely Carmichael, Augustus Lushington and Ella Sheppard.

"I heard about Raven's program 'Music and the Movement' at the Artists' Laboratory Theater and asked her to be a guest on my show, 'The Vinyl Hour,' to talk about music that's been central to the Civil Rights movement and how music can transcend boundaries between people," says KUAF station manager Leigh Wood. "She was fantastic. One minute she was talking about finding this music from her parents or as a teenager, and her face would light up in delight. The next minute, she was educating me on events in the civil rights movement and Black history I had no idea about. I had goosebumps the entire time. She's one of those people whose passion and knowledge truly move people -- she's a born teacher.""

That's probably because from Cook's earliest memories, she was learning. Cook was born in Arizona, where her parents were stationed on an Air Force base, and was a toddler during a time -- much like this one -- when the country was roiling from social unrest. It was 1992, and tensions were brought to a boiling point over the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers accused of excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King. At the same time, conservative politicians in Arizona were fighting efforts to declare Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday a state holiday, something every other state in the union had made official. Warren-Cook says she was frustrated by the racism she was witnessing both in the armed forces and by the Arizona lawmakers, so the family decided to move back to Arkansas, from which both parents hailed.

"I told my mom that I didn't even want [Cook] to have a Social Security number that resembled anything to do with Arizona," remembers Warren-Cook. "I think I was protective of her. I didn't want Raven to be introduced to our world too soon."

Education inequities

Once in Little Rock, the couple decided to send Cook to a private, all-Black council school affiliated with their church. Warren-Cook says it was a choice born from her experiences as a child growing up in El Dorado.

"When I was in first grade, that was the first year of integration in the schools down there," she recalls. "All of the teachers called us the 'N-word' and told us all to go home and tell our parents. My brother was a senior at that time, and there were riots [at the high school] daily. When we would walk back to our side of town, the white boys in their cars would call us the 'N-word' and chase us. I never wanted Raven to experience anything like that. That's why it was so important that she live in a bubble and just be encompassed by love."

"It was really an oasis," says Cook of her formative years. "I really didn't know a lot of white people. I didn't come in contact with a lot of white people. I knew the ones that were on TV, like President Clinton, and that was about it. And it was fine. Nobody made a big deal about it. It was just the way life was."

The bubble was broken in the most heartbreaking, horrifying way: Cook was in second grade when she overheard two of her teachers talking about the brutal Texas murder of James Byrd Jr. by three white supremacists. Byrd was chained to and dragged behind a truck for three miles, conscious most of the way.

"When our teacher came back in, she was confronted with the question: 'What's a lynching?'" remembers Cook. "So she had to make a really important decision -- 'Do I have this talk, or not?' And she went there. She really went there, and she talked about it. And, really, as a young person, it made me super aware that my Blackness was perceived in the imagination of others as threatening and dangerous. And it could result in me being killed -- which scared me.

"I had a consciousness of racism, but, when I was in the second grade, I didn't think it was still happening. I thought, 'Oh, that was years and years ago, and Martin Luther King Jr. made it all better.'"

"It was thrust on me to have the talk about us in the world," says Warren-Cook. "I thought I would have more time to prepare, but it just popped up. Her dad and I had to speak from the heart. We watched the news, we talked about our own personal experiences and those of our parents. We started having conversations about it."

"In the third grade, our teacher was the minister at our church, and he wanted to ensure that we were equipped with the knowledge of our history," says Cook. "He centered it in liberation. He made sure we felt empowered as Black people. At my school, they made sure that we didn't just think about Black America, but that we had an international consciousness of the connection of African peoples around the globe. We worked with African children's choirs that came to our church. We met civil rights pioneers. It was a very important foundation for me as an educator, as someone who works currently to teach people about the realities of the Black experience in America."

By the time Cook hit the middle grades, says her mother, the family decided it was time to expose her to a different kind of experience -- a transfer to the public school system. "We talked about it, and we decided she was ready," says Warren-Cook.

In fact, Cook had been given a foundation that instilled confidence and a strong sense of self. Her parents made sure that her dolls reflected her skin color, that she was exposed to television and movies that featured Black actors in prominent roles, and that she had access to learn about Black American's accomplishments in history and art and culture. So when she first started public school, she was quick to notice how little Black people's role in American history was emphasized.

"It was a culture shock for me," Cook says. "People weren't talking about Black history. I felt like, 'What happened?' I definitely would push my teachers to have conversations about Black people. I would ask, 'Where are the Black people in this picture?' I would make it a priority to try to figure out where I was in the stories, in the account. I would reach out and ask, 'Can we talk about Black history in class?' It was just something I needed. And it was a little challenging to get that in Arkansas through public school."

An inspirational high school teacher named Ruthie Walls -- "she was like a light to me," says Cook -- identified Cook's talent for teaching her senior year.

"She said, 'You have a gift, and I think it should be shared,'" remembers Cook.

#BlackatUARK

With Walls' words ringing in her ears, Cook set off for the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff after high school graduation, then transferred to Fayetteville for the African-American Studies program. While there, she would hold the position of president of the Black Student Union and was active in the Greek system, positions that would imply a sense of belonging -- but, says Cook, that was never the case. She references the recent #BlackatUARK hashtag that has been trending on Twitter. Inspired by the social justice protests that have sprung up all over the country in the wake of George Floyd's death at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, Black UA students are sharing their experiences of racism and exclusion on campus. Cook says she recognizes her own experiences in the stories these students are sharing.

"It was tough," she says. "It was mentally, physically, emotionally, spiritually tough. And lonely. I remember feeling very, very lonely because I was learning about Blackness in a radical way at the time. It kind of made me resist the teachings of Dr. King, because, a lot of times, people weaponized Dr. King against us. They still do it to this day. They would tell us, 'You need to be more like Dr. King -- why can't you talk more like him?' which made me really angry. I started to become a student of Minister Malcolm X, and I got really, really into it. I would watch his documentary in the morning, before I would go on campus, to kind of suit up for battle. And when I got home, I had my sorority sisters and my fraternity brothers come to my house -- they called it 'The Museum' because I had tons of paintings and pictures and books of Black people all around the house. It was always a space where people could go and learn about Black history in a radical way, and talk about it in a way that we couldn't always talk about it on campus."

Cook says her more "radical" ideas weren't welcomed by a lot of her instructors and professors. She was disappointed to find that rejection from some Black teachers as well as white.

"I think it was because of the culture here," says Cook. "I dealt with a lot of challenges from Black administrators who thought I was too outspoken, I was too disrespectful, things like that. That was really difficult, to see people who looked like you in such a small number, seeing your revolutionary spirit as problematic instead of something that could be channeled into something really powerful. That was hard.

"I had a few [Black teachers], however, who saw me as a diamond in the rough, and they would pull me to the side and have a real dialogue with me about how I was feeling and what I was thinking. Most of the time, they would be Black women. So that was really important to me as well."

Teaching truths

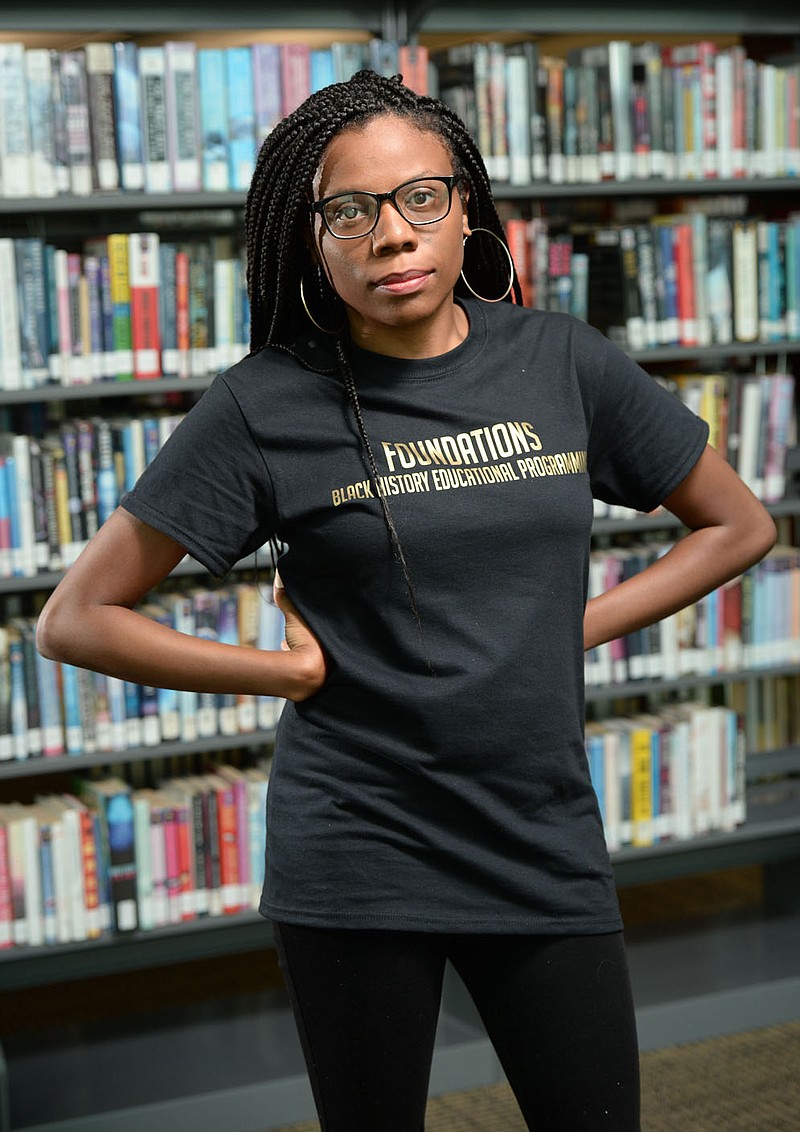

Cook left the UA somewhat disillusioned and temporarily moved to Texas where she worked on the campaign of Wendy Davis, who ran for governor in 2014. In partnership with some of her Greek friends from UA, she started an educational company called "Foundations: Black History Educational Programming" and, soon, was developing and delivering Black history curriculum via the Internet every Sunday.

"Leaving the University of Arkansas actually gave me an opportunity to educate myself in a way that made me feel more powerful than I felt on campus," says Cook. Her education experience eventually led her to the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in Little Rock, a museum that focuses on Arkansas Black history, and, then, Crystal Bridges.

But the work she does outside of the museum is her passion, and much of that she does for free. Her subject area is wide and varied: The Washington County League of Women Voters sponsored a lecture at the library delivered by Cook on the cultural and political contributions made to American society by Black women; she presented a series called "Inspire 365: A Journey through the Black Experience" at the Omni Center for Peace, Justice & Ecology in Fayetteville; presented "Vision and Responsibility: Responding to Racist Imagery in American Culture and Art" at the Spring Arts and Culture Festival at Northwest Arkansas Community College; and spoke in front of thousands gathered at the 2018 Women's March.

"Raven is an effective teacher because she's herself in her teaching -- she talks about her feelings, her emotions, her perspective and her experience," says Wood. "I think that's vitally important -- because we're at risk of turning learning about systemic racism and anti-racism into just an intellectual exercise, and we miss the human aspect of it. Raven is always humanizing history, and I think that's why she reaches so many people. It's on the rest of us to pay attention."

"I'm just trying to ensure that people are conscious of race in America and the history, the inequity," says Cook. "And I'm trying to make sure people feel like they're empowered to keep doing the work."

Vital to that cause is keeping these issues at the forefront of the national conversation, she says. Both Cook and her mother mention having to have "The Talk" with Cook's 19-year-old brother --a tough discussion of the dangers young Black men face in today's society -- and Warren-Cook says she worries every time either of her children leaves the house; she has an app on her phone that will alert her if either is pulled over while driving.

"It's a fearful time to be a mother," says Warren-Cook.

When George Floyd was killed in May, several other high-profile murders of unarmed Black people -- Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, to name but two -- had come and gone in the nation's headlines just months before, and there were no national protests, no movement toward systemic change. So what made people finally start paying attention through more than one news cycle?

"I honestly think covid-19 played a big role in it," Cook says. "I think it required people to sit still for a minute, and it removed a lot of the distractions. I was talking to a friend of mine the other day, and he told me that the NBA playoffs would have been happening around the time that George Floyd was murdered. And if that had happened, people would have said, 'Oh, that's so sad,' and turned back to the game. But now, we don't have sports, we don't have things to watch, to use to try and ignore it. Companies are starting to make 'Black Lives Matter' sections of their streaming services. And, really people are just starting to be confronted by this old foe in a way they can't run from."

Though her immediate plans are to stay in the education field, when asked, Cook doesn't rule out the possibility of a future run for public office. The subject has been raised to her by others in her life who think her empathy, communication skills and desire for positive change would make her a natural in politics. Talk with her about politics, though, and the subject comes back around to education -- and how key it is to creating the next generation of powerful leaders.

"I think [a more robust Black history curriculum in schools] would be empowering for young Black people," she says. "I think it would also challenge young white people to think about it. I think if we taught some of these young voices, we would really help students come to their own process of being leaders. Before I start a class with young people, I always tell them, 'You're the next generation of leaders. So this is a necessary thing that you have to learn for your leadership skills.' They ask tough questions, and we talk about them very honestly. It helps them to have the language and the tools they need to work in all different types of movements."

Cook is determined to be part of the process that gives young people that language, those tools. Among her duties at Crystal Bridges is conducting professional development sessions with Arkansas educators in which she trains teachers how to teach about race and Black history.

"Having them take Black history back to their classrooms, I feel like I'm making a difference," she says. "I'm trying to make a difference."

More News

Self Portrait

Raven Cook

My greatest fear is not fulfilling whatever God has for me to do because of fear.

Few people know I am incredibly nervous when I speak.

I would say I am at my best when I have the space to be creative.

If I’ve learned one thing in life, it’s all things are working together for the good even though it may not look that way.

One word to sum me up would be sweet.

People who knew me in high school would say I was just as passionate about Black History as I am today.

My greatest strength is my desire to be of service no matter what!