Daniel Lewis Lee was a cocked, fully loaded gun.

That's how prosecutors described him to jurors as he stood trial in a triple-murder case 21 years ago.

They said Chevie Kehoe, Lee's friend and fellow white supremacist, pointed Lee -- that "loaded and cocked gun" -- at an Arkansas family in 1996.

Both men were convicted in the slayings, in addition to other federal charges. While Kehoe was sentenced to life in prison, Lee received a death sentence, which was carried out Tuesday by lethal injection.

It was against the wishes of the relatives of those killed.

"From the beginning, we have said we don't think Daniel Lee should have the death penalty," said Monica Veillette, a niece and cousin of two of the victims, in an interview several weeks before the execution.

The slaying of the Pope County family of three is one of the grisliest in the state's history, but Lee's death sentence has confounded legal observers, the victims' family and even the federal judge who presided over his trial and was ultimately forced to hand down the sentence.

In January 1996, Kehoe and Lee, then 22, entered a Tilly-area home disguised as federal agents, according to court records.

There, they waited.

The home invasion was the start of a plot to establish an all-white nation in the Pacific Northwest, authorities said at the time.

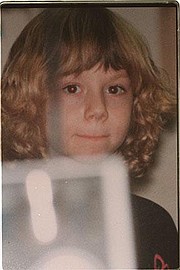

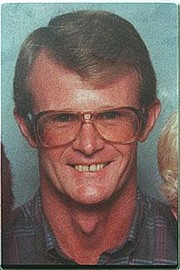

The home belonged to William Mueller, 52; his wife, Nancy, 28; and her 8-year-old daughter, Sarah Powell. They weren't home when the killers sneaked inside.

When the family returned, Kehoe and Lee subdued them with stun rods and robbed them, according to testimony from the trial. Before fleeing, the killers duct-taped plastic bags around the heads of all three to suffocate them, then dumped their bodies in the Illinois Bayou near Russellville.

It would be months before the bodies were found by fishermen and nearly two years before Kehoe and Lee were caught.

The maze of clues that detectives tracked to the two men ended with a stunned courtroom as a jury announced that Lee should be put to death. Just days earlier, the same jury recommended a life sentence for Kehoe.

The sentencing disparity has perplexed lawyers and the Muellers' relatives for the past two decades.

They wondered: How could the same jury hand down different punishments to two men convicted of the same crimes? Furthermore, prosecutors concluded that Kehoe planned the slayings, and trial testimony indicated that it was Kehoe who murdered the 8-year-old girl after Lee refused.

At Lee's sentencing hearing, prosecutors conjured the gun metaphor. The Mueller family died because Lee was the monster, and Kehoe unleashed that monster, they said.

Ultimately, jurors took that message to heart. They weighed the pasts of the two killers, determining that Lee was too dangerous to be left alive.

Lee showed a pattern of violence through his youth and young adult life, court records show. He assaulted his mother, sister and pregnant girlfriend, U.S. attorneys said. He participated in two killings -- the first when he was 17.

Lee -- who eventually renounced his white supremacist beliefs, according to his attorneys -- had an explosive temper. He flashed it often. If there were ever people in his life who tried to make him better, nothing they did worked.

His nickname was "Cy," short for "Cyclops," according to court records. He earned the name after losing an eye during a bar fight in Spokane, Wash.

His strongest supporter during his 1999 murder trial was his mother, Lea Graham. But she was forced to admit on the witness stand that she filed petitions against her son. Those petitions revealed instances when he attacked his family.

His father left when Lee was a child. His desire to find a father figure led him to a man in his community who had strong ties to the Ku Klux Klan, according to court documents.

Later in life, he found a brotherly figure in Kehoe.

"He was very traumatized at a young age," said Ruth Friedman, one of the attorneys representing Lee, in an interview with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. "People with those kinds of backgrounds are looking for something. They want a sense of belonging. If someone takes them in, that's where they're going to stay."

Kehoe was the most culpable of the two killers, prosecutors and investigators told the jury. That is what Nancy Mueller's relatives, who sat through the entire trial, left believing.

"Chevie got life and then [the U.S. attorney's office] asked us, 'Should we take death penalty off the table?,'" Veillette recalled. "Our family said to take it off the table. Kehoe planned it all and murdered Sarah."

But it wasn't taken off the table -- a decision that was made 1,000 miles away in Washington, D.C.

From the beginning, prosecutors wanted the death penalty for both men.

In September 1997, then-Pope County prosecutor David Gibbons fielded a question from a television reporter during a media conference after the killers' arrests. He was asked whether he had a strong enough case for the death penalty.

"What do you think of an 8-year-old girl choked to death and drowned?" Gibbons replied. "I'm sure we'll get the death penalty."

By December, it was no longer a local decision. The U.S. attorney's office took over the case.

At that time, the U.S. government had not executed anyone in more than 34 years.

Since the end of the trial, Veillette and others have theorized about what led jurors to recommend life for the mastermind and death for the one who refused to kill Sarah.

Veillette said appearances played a part.

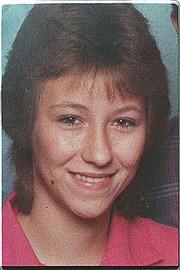

"It's not even a theory at this point," she said. "When you look at Danny Lee with that [Nazi] tattoo on the side of his neck and that eye, it's a very scary picture.

"During the trial and in those old pictures, Danny Lee looked like a white supremacist. He looked like someone who could murder a family. Chevie Kehoe looked like a kid you went to school with. You wouldn't suspect he was a murderer if you sat next to him."

What transpired during the sentencing phase also mattered. The jury was swayed by the two different pictures painted for the men.

Kehoe's attorneys portrayed him as someone whose potential wasn't realized because of poor parenting. Former teachers and acquaintances talked about a promising kid whose potential was thwarted, in large part, by a bigoted, strong-willed father who pulled him out of school at 15.

Kehoe cried as his attorney, Tom Sullivan, gave his closing arguments.

"He did an evil thing," Sullivan told jurors. "But he's not evil."

Meanwhile, prosecutors portrayed Lee as someone who was repeatedly violent.

Prosecutors said Lee spent time in hospitals and youth homes, but he was often removed from them because he was violent toward staff members.

They also cited a 1988 report that disclosed Lee had an IQ in the superior range.

The defense's mental health expert said Lee joined the skinhead movement because he wanted to fit in.

The prosecution's mental health expert said Lee told him that he joined so he could have sex with women, drink beer and get into fights.

Jurors learned of a throat-slashing death of a teen in Oklahoma that Lee was involved in as a 17-year-old. The teen was forced down a manhole that led to a sewer.

Lee admitted to police that he forced the teen into the hole and gave his cousin the knife that was used to kill the victim.

Lee pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of robbery in that slaying and served a short stint in juvenile detention.

The prosecutor emphasized during his closing arguments that Lee never took advantage of the second chance he was given. Instead, Lee maintained a "love of violence."

The jury was swayed, and it agreed with prosecutors that Lee was too dangerous to keep alive.

A TRICKLE OF CLUES

When authorities pulled the decomposing bodies of three people out of the Illinois Bayou, the Mueller family had been missing for more than five months.

William Mueller's Army jacket was still on him, court documents show. Wide strips of duct tape covered his eyes, mouth and chin. A handcuff was around his wrist.

Nancy Mueller's legs were bound with zip ties. Her body was still attached to a rock.

Sarah's head was covered by a plastic bag. Her arms were crossed around the front of a rectangular rock attached to her. Yards of duct tape fastened the rock to her small body. The rock weighed 69 pounds, 12 pounds heavier than the average 8-year-old girl.

Veillette, who was 19 at the time, remembers her family getting the call from a detective.

"At that point ... you hope it's not true," she said. "But also, how many other three-person families had gone missing? It was an awful, awful feeling."

The killers wouldn't be caught for another year. The clues that trickled in would lead to an elaborate story about one man with twisted ambitions and another who followed his lead.

Kehoe and Lee boasted about the murders to others. Police statements and the testimonies of those people revealed what happened inside the Mueller home on Jan. 11, 1996:

Kehoe and Lee drove to Pope County from Washington state to steal weapons, cash and other items from the Mueller property.

The family wasn't home when they arrived. They were dressed in black clothing with markings similar to those worn by federal agents. They covered their faces.

Lee hid behind a couch and waited for the family to enter the home. Kehoe was behind a washing machine.

Bill and Nancy Mueller and Sarah walked through the front door. The lights came on, and one of the suspects yelled: "ATF! Raid!"

The victims were bound and had plastic bags placed over their heads.

Bill Mueller's survival instincts kicked in. Kehoe told people that he "fought like a son of a b."

Kehoe took the stock of his shotgun and slammed it against Mueller's head, incapacitating him.

He then ordered Sarah to tell him where her parents kept their valuables.

Kehoe and Lee suffocated the victims by wrapping duct tape around their bagged heads. Lee balked at harming Sarah.

They took the bodies to the bayou, taped heavy rocks to their bodies and dumped them in the water.

The family wasn't chosen at random; the Muellers and Kehoes had a history.

At first, relations were good. The Kehoes babysat Sarah, and Nancy Mueller once made a bib for one of the Kehoe children.

Things changed after a disagreement between Bill Mueller and Kirby Kehoe, Chevie's father. In February 1995, the Mueller home was burglarized -- a crime authorities tied to Kirby and Chevie Kehoe years later.

Mueller never filed an insurance claim on the stolen cache of weapons estimated to be worth more than $50,000. He suspected Kirby Kehoe was responsible and confronted him. Chevie Kehoe thought Mueller had threatened his father, whom he revered.

Chevie wouldn't forget it.

FRESH LEADS

In December 1996, after months of little progress in the investigation into the deaths, one of Bill Mueller's rifles appeared after the arrest of a white supremacist stopped in South Dakota for parking in a handicapped space, according to court records. It was a Bushmaster semi-automatic rifle, thought to have been stolen when Mueller was killed. The man arrested for possessing the rifle told authorities that Kehoe had sold it to him.

Before that, a .45-caliber handgun appeared in a Seattle pawnshop. The gun's owner, a drifter, told police that he got it from Kirby Kehoe. It was stolen from Mueller during the first burglary in 1995, federal agents said.

Those weapon confiscations led to Chevie Kehoe becoming a person of interest in the Mueller slayings. It breathed new oxygen into an investigation that led authorities to a series of unsettling discoveries from Washington to Ohio.

An acquaintance of Kehoe's, Faron Lovelace, was a fugitive in late 1996, wanted in the kidnapping and death of fellow white supremacist Jeremy Scott. Police caught up to Lovelace in a dilapidated cabin in the deep woods of Idaho. Near the cabin, police found a trailer that had been reported stolen out of Arkansas.

Inside were guns, ammunition and camping equipment that had been stolen from the Mueller property, police said. Like the others, Lovelace told police that he obtained them from Chevie Kehoe.

During his discussions with police, he disclosed much more about Kehoe.

In the murder indictments for Kehoe and Lee, it was stated that Kehoe witnessed Lovelace killing Scott in Idaho in 1995 and helped him bury the body. They wanted him dead because "his mouth was too big," the indictment stated.

Kehoe was operating a terrorist organization called the Aryan Peoples Republic, authorities said. His goal was to disrupt the federal government and start a whites-only nation in the Pacific Northwest.

THE ARRESTS

The life and crimes of Chevie Kehoe nearly came to an end Feb. 15, 1997, in Wilmington, Ohio.

Kehoe and his younger brother, Cheyne, were stopped for driving with expired, out-of-state tags. A police dashboard camera captured a shootout between police and Cheyne that was broadcast around the U.S.

The brothers escaped and reunited with their family at a campground. They traveled west and stayed in a camp in Utah in June 1997. Cheyne Kehoe, though, grew to fear his brother and fled one night. He wound up in Washington and surrendered to authorities.

He led investigators to a white pickup. The white coat was painted over the factory-painted blue. Detectives matched paint flecks from the truck's original coat of paint to those found on the duct tape strapped to the Muellers.

Cheyne Kehoe also told investigators where to find his brother, and Chevie Kehoe was arrested by the FBI outside a farm supply store in Utah.

Lee was arrested at his mother's home in Yukon, Okla., in September 1997.

Investigators learned that Lee returned to Oklahoma after his trip to Arkansas. He took with him a customized Remington semi-automatic, sawed-off shotgun that belonged to Bill Mueller.

He traded the weapon for a tattoo and bragged to a friend that he had gone to Arkansas, "waxed some people, wrapped them up and threw them in a swamp."

Gloria Kehoe, who testified against her son at his trial, told jurors that both her son and Lee described to her what they had done in Arkansas. They jokingly said they put the Mueller family "on a liquid diet," transcripts show.

The motive behind the killings, investigators said, was two-pronged.

Chevie Kehoe wanted Mueller dead so he wouldn't retaliate against Kehoe's father. He also knew that Mueller kept loose cash in his house and more weapons on his property.

The men planned to use the money and weapons to launch their whites-only nation.

DEATH SENTENCE

U.S. District Judge G. Thomas Eisele, the presiding judge in the case, resisted sentencing Lee to death.

Days after jurors returned with their recommendation, the judge announced there had been a "fatal failure of communication" that could have resulted in Lee being sentenced to life in prison.

After jurors recommended life for Kehoe, prosecutors sought instructions from then-Attorney General Janet Reno about pursuing the death penalty for Lee.

Reno was unavailable, so Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder made the decision for her. Holder, who would become attorney general less than a decade later, said he consulted with the Death Penalty Review Committee in Washington, D.C., and decided not to withdraw the office's pursuit of a death sentence.

Eisele said that if he had known Reno wasn't available to make the decision, he would have waited.

In March 2000, after more legal wrangling, Eisele ordered another sentencing hearing for Lee. He did so based on his belief that he had given too much leeway to the government when it cross-examined one of the defense's witnesses.

In December 2001, a federal appeals court ruled that Lee must be sentenced to death. Five months later, Eisele finally imposed Lee's death sentence.

In 2015, Eisele, who is now deceased, wrote a letter to the attorney general, Holder, stating that executing Lee would be "unjust" and pointing out that Kehoe was "without question" the more culpable of the two.

Veillette said she agreed. Kehoe, to her, remains the villain who looms largest in her life.

The entire process has given her insight into capital punishment that most others don't have.

She was noncommittal on answering whether she was for or against the death penalty, but she has a lot of doubts about it. Primarily, she doesn't think it can ease any pain.

"Oh, they think they're doing us a favor," she said. "Yeah, fry 'em. That's what people often say, but none of them have had to sit for 24 years waiting for something to happen.

"It really isn't helpful to family members and their grieving. For us, it has not been helpful for our healing. We will never get more answers."

Veillette grew up in Arkansas and moved to Spokane years ago. She said she visited the area with her family and fell in love with the geography and the people.

She wanted to create space between herself and the worst memories of her life, but she now lives in a city where the remnants of the Kehoe family reside.

She often goes to public events and speaks to crowds about how white supremacy has had such a devastating effect on her family.

She has been approached by people who knew Chevie Kehoe, who is imprisoned in Colorado.

She gave a speech at an anti-hate vigil in Spokane Valley about the dangers of raising children in areas where racism is rampant.

"One of the speakers said: 'Hey, I knew those people. I knew the Kehoes. I was in that group, and now I'm out,'" she said.

When she heard the speaker say that name, it chilled her, she said.

The mention of Daniel Lee doesn't put any fear into her.

The other name still does.