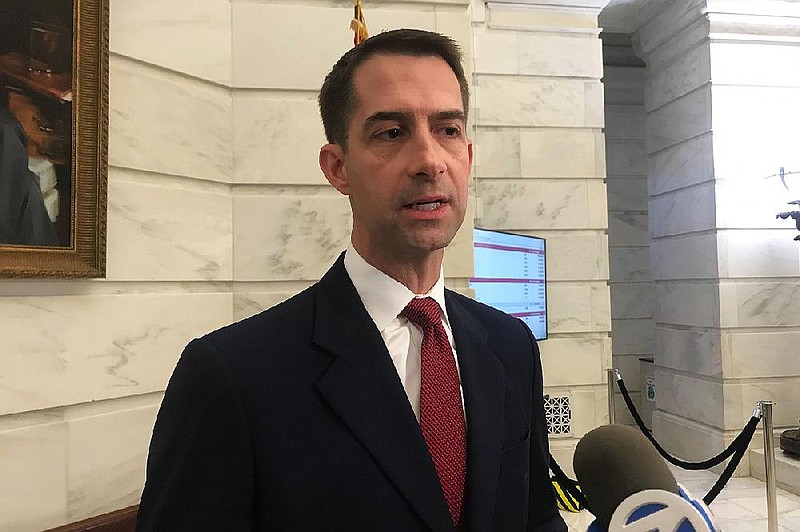

WASHINGTON — A New York Times-based school curriculum emphasizing American slavery instead of American independence has been targeted by U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton.

The Little Rock Republican introduced legislation Thursday that would prevent the use of federal tax dollars to spread the historical reinterpretation in the nation’s classrooms.

While labeling 1776 as the nation’s “official birth date,” the 1619 Project seeks “to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year.”

Timed to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the arrival of African slaves in the Virginia colony, the 1619 Project was launched last year by the Times.

Arguing that it is “finally time to tell our story truthfully,” the project “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

The project’s mastermind, Nikole Hannah-Jones, was awarded this year’s Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

A curriculum based on the project, which includes essays, poems, photographs and short fiction by a variety of contributors, was also created.

The result of a partnership between the Times and the nonprofit Pulitzer Center, the curriculum is intended for use in primary and secondary schools nationwide.

COTTON’S PROPOSED LAW

If the Saving American History Act of 2020 becomes law, however, school districts using the 1619 Project curriculum could face financial consequences.

Cotton’s legislation labels the project “a distortion of American history.”

“The 1619 Project is left-wing propaganda. It’s revisionist history at its worst,” he said in an interview Friday.

[Audio not showing up above? Click here to listen » arkansasonline.com/cottoninterview/]

Hannah-Jones did not respond to a request for comment Friday. In a tweet, she said Cotton’s bill “speaks to the power of journalism more than anything I’ve ever done in my career.”

In a written statement, Times spokesman Jordan Cohen said the project “is based in part on decades of recent scholarship by leading historians of early America that has profoundly expanded our sense of the colonial and Revolutionary period. Much of this scholarship has focused on the central role that slavery played in the nation’s founding.”

Recent scholarship “has helped challenge prevailing narratives about our founding that prioritized the ideals of the Revolution while paying scant attention to historical realities.”

In her introductory essay, Hannah-Jones suggests that the Revolution was a reaction to the British abolition movement, arguing that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery [and]…ensure that slavery would continue.”

That “fact,” she said, has been “[c]onveniently left out of our founding mythology.”

Critics say many of the leading revolutionaries opposed slavery. New England, cradle of the revolution, was also a stronghold for anti-slavery sentiment, they say.

Five renowned historians — Sean Wilentz and James McPherson of Princeton, Brown University’s Gordon Wood, Victoria Bynum of Texas State University and James Oakes of the City University of New York Graduate Center — challenged Hannah-Jones’ premise last year, and urged the Times to “issue prominent corrections of all the errors and distortions presented in The 1619 Project.”

The Times defended the project, but later walked back one key claim. Preservation of slavery, it now states, was a key motivator for just “some of the colonists.”

While lauded by the Pulitzer judges, the 1619 Project has been condemned by many conservatives, including President Donald Trump. Now it’s under fire in the U.S. Senate as well.

FEDERAL FUNDS THREATENED

If Cotton’s legislation passes, school districts that embrace the curriculum would no longer qualify for federal professional development funds, money that is intended to improve teacher quality.

Federal funding would also be lowered slightly to reflect any “cost associated with teaching the 1619 Project, including in planning time and teaching time.”

Funds tied to low-income or special-needs students would not be affected.

The secretaries of Education, Agriculture and Health and Human Services would create “prorated formulas” to determine the size of the reduction in federal money for schools adopting the curriculum.

“It won’t be much money,” Cotton said. “But even a penny is too much to go to the 1619 Project in our public schools. The New York Times should not be teaching American history to our kids.”

Capitol Hill isn’t the place where curriculum decisions are typically made, Cotton acknowledged.

If educators want to use the materials, they’ll still be free to do so, he said.

“Curriculum is a matter for local decisions and if local left-wing school boards want to fill their children’s heads with anti-American rot, that’s their regrettable choice. But they ought not to benefit from federal tax dollars to teach America’s children to hate America,” he said.

DISAGREEMENT ON HISTORY

Critics have accused the project of misrepresenting colonial views on slavery, arguing that anti-slavery sentiments were stronger in some of the colonies than in England. In the midst of the Revolutionary War, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed its own Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. In Massachusetts, the judiciary struck down “perpetual servitude” by the time the Treaty of Paris ended the conflict.

Cotton, who opposed recent efforts by U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., to remove Confederate names, monuments and symbols from military sites, has accused the 1619 Project of being “racially divisive.”

“The entire premise of the New York Times’ factually, historically flawed 1619 Project … is that America is at root, a systemically racist country to the core and irredeemable. I reject that root and branch,” Cotton said Friday. “America is a great and noble country founded on the proposition that all mankind is created equal. We have always struggled to live up to that promise, but no country has ever done more to achieve it.”

Asked what he’d say to people who consider Confederate statues and military base names “racially divisive,” Cotton noted that Arkansas is already taking steps to remove its own segregation-era statues.

“I have no problem with people debating that in a constructive, reasoned, deliberate fashion,” he said. “What I can’t tolerate, what I think no one should tolerate, are angry mobs tearing down statues of anyone. They tear down a statue of [Confederate Gen.] Robert E. Lee today; tomorrow they come for [Presidents George] Washington and for [Abraham] Lincoln and for [Ulysses S.] Grant.”

In the interview, Cotton said the role of slavery can’t be overlooked.

“We have to study the history of slavery and its role and impact on the development of our country because otherwise we can’t understand our country. As the Founding Fathers said, it was the necessary evil upon which the union was built, but the union was built in a way, as Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction,” he said.

Instead of portraying America as “an irredeemably corrupt, rotten and racist country,” the nation should be viewed “as an imperfect and flawed land, but the greatest and noblest country in the history of mankind,” Cotton said.

The Times is a frequent target of the senator’s criticism.

Its editorial page editor, James Bennet, resigned last month after running a column by Cotton on the possible use of military troops to quell unrest in the nation’s cities. The paper later said that the piece had fallen “short of our standards and should not have been published.”

In his written statement Friday, the Times spokesman portrayed the 1619 Project as a helpful resource.

“It is in part due to these prevailing narratives that 60% of teachers polled in a 2017 [survey] said that they believed their textbook’s coverage of slavery was inadequate. We’re proud that, in partnership with The Pulitzer Center, we’ve been able to help address that problem by making The 1619 Project available as a course supplement that was taught last year in schools in all 50 states,” he said. “We believe it is important for American students to understand the truth about their country’s history. To paraphrase the historian Alfred F. Young, we should not be so protective of the achievements of equality that we are unwilling to come to grips with inequality.”

STATE USAGE UNKNOWN

Arkansas Department of Education officials Friday couldn’t say whether the 1619 Project is widely used in the state.

“Since we are a local-control state, the decision of what educational textbooks, resources, and materials a school or district uses is left entirely up to schools and districts,” spokeswoman Alisha Lewis said. “We do not collect or have any data to indicate which schools have chosen which curriculum.”

Lucas Morel, a Washington and Lee University politics professor and former John Brown University faculty member in Siloam Springs, portrayed Hannah-Jones’ writing as flawed, though he encourages his own students to study it.

“If it was the only thing kids were reading about U.S. history, it would actually do more harm than good, in part because [there is] so much that is left out,” he said. “What it leaves in is half-truths, falsehoods, bowdlerizations [and] caricatures.”

Brian Keith Mitchell, a University of Arkansas at Little Rock history professor, said the 1619 Project separates rhetoric from reality when it examines the Founding Fathers.

“The concept of us having a nation conceived in liberty and justice and freedom, I mean it was sort of a farce,” Mitchell said.

He also dismissed claims that the 1619 Project is racially divisive.

“How would teaching what actually happened be divisive?” he asked. “The whole point of … being educated is to have correct information.”

It’s hard to overstate the role of slavery in the American story, he said.

“It’s instrumental in the formation of wealth here, instrumental in the mobility of our nation. The buying and selling of slaves and the things that they produced were the cornerstone of American capitalism,” he said.

“There would not be an America, at least not a First World America, without slavery,” he said.