Not having kids is a good way to save money. Not that I would know. I wouldn’t trade my kids for a bigger bank account — on most days.

Being childless can be really good for the arts. Ask Virginia and Ed Fultz, of Albuquerque, N.M. Fifteen years ago, the married art lovers decided to leave their entire estate to their local museum. That is everything — their house, car, investment portfolio, and art collection — altogether worth a few million, give or take.

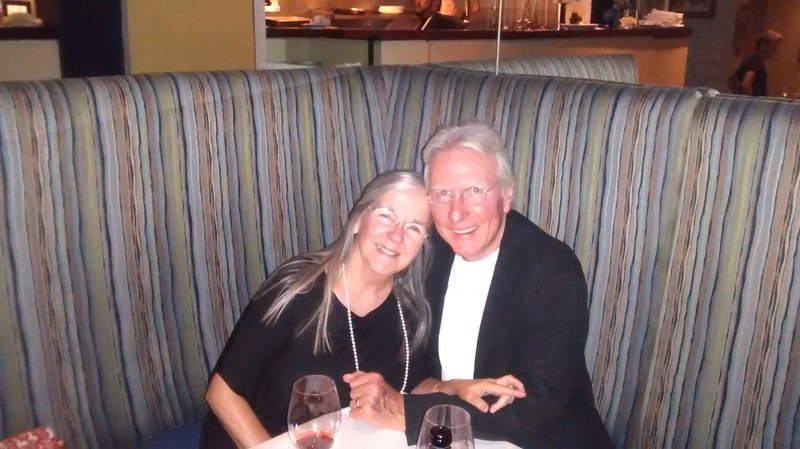

Ed and Virginia met as teenagers while attending West Texas State College. They married during their junior year, 55 years ago. After college, they taught high school in El Paso for 10 years and made the most of their summers traveling.

“We didn’t grow up in homes with art,” Virginia said. “What we knew of art, we’d learned from books.” However, during the summer of 1968, that changed. Over three months they visited every country in Western Europe. “We did the Europe-on-$5-a-day plan because it fit our teacher budget.” They hit every major museum.

“That first trip to Europe was so eye-opening,” Ed said.

“It was like this grand feast,” Virginia added.

On their first visit to the Louvre, in Paris, she said, “We could barely afford lunch. Then the waiter brought this hors d’oeuvres tray and two glasses of wine that we couldn’t afford. We saw this nicely dressed gentleman sitting nearby and knew it was from him.”

Art patrons are a generous bunch. Virginia and Ed are paying those moments forward.

Ed left teaching and took a management job with a trucking company, and in 1981 was transferred to Albuquerque, a city he and his wife loved for its art and culture. Because no teaching positions were available, Virginia began selling real estate.

They continued to travel and buy art. Today their collection includes pieces from other countries and many from their native Southwest.

“We don’t buy what someone else likes,” Ed said. “We buy what we love. It doesn’t have to have value, nor do we need to think it will become valuable,” although some of their pieces are by artists who have become known.

As for whether any of it will wind up in the museum, the Fultzes have no expectations. Though the Albuquerque Museum has first dibs, “if they say they don’t want anything, we will not be offended,” Virginia said. “We’ve gotten our enjoyment.”

Meanwhile, they continue to appreciate their local museum’s collection. “We often go and spend a couple hours there, have lunch and a glass of wine at the cafe and talk about art,” Virginia said. “Every time I go, it thrills me to know they will benefit from us someday. They’ve given us so much more than we’ll ever give them.”

To prepare their art collection for the ultimate handoff, when items will either go to a museum or be sold for cash, the Fultzes have an art file. Each piece has a folder with information about the artist and the artwork, and the story behind how they got it.

“The problem is we have to quit collecting,” Virginia said.

“That’s not going to happen,” Ed said.

“We are so behind on our files.”

“If you saw our walls, you would laugh.”

“Truly, we are not allowed to go to an art show for a year.”

“We’re going to one next week.”

Deciding to leave your estate to a cause you love is step one. The next challenge, the Fultzes found, becomes how. Here’s what they learned:

• Name the right entity. In 2005, the Fultzes named the Albuquerque Museum as their beneficiary, but last year, they met Emily Blaugrund Fox, executive director for the museum foundation, and learned they should name the Albuquerque Museum Foundation as beneficiary. The city owns the museum and so controls donations to it. “We didn’t want some city mayor to use the money for another project,” said Ed, who updated his will accordingly. The foundation is set up solely to support the museum.

• Don’t do it alone. Work with an attorney to make sure your will conveys what you intend, and is valid under your state’s law. An attorney can also make sure your will spells out exactly what you want to leave and to whom, lists all assets, and names the executor.

• Be specific. Make clear how you want your gift to be used. The Fultzes earmarked their donation for art acquisitions. “Others may designate funds to support exhibitions, capital improvement or education,” Fox said, “but don’t restrict the gift too much.”

• Find a trustworthy representative. Naming your executor, or personal representative as they’re called in some states, is a pivotal choice. “We did not want a relative to do this,” said Ed. “We did not want to inconvenience our nieces and nephews or cause any infighting.” Initially, they’d asked a younger friend to handle their estate. After that relationship changed, they asked Fox if she would do the honors, so all the money could go to the museum. That posed a conflict, so Fox declined. “We need the separation in case the family has questions later. We can’t open the museum to liability,” she said. Finally, the Fultzes hired a trust company. For a percentage of the estate, the company will handle the sale of the art and other assets, and disburse the proceeds.

• Tell the recipient. Do let whomever you’re leaving an asset to know you’ve named them in your will, Fox said. Be sure they want it. “We may not want grandma’s hanky collection, cherished as it is.”

Syndicated columnist Marni Jameson is the author of five home and lifestyle books.